Today’s post is timely—many instructors are putting together syllabi for fall courses. This year, Johns Hopkins’ faculty who teach undergraduates are being urged to include course learning goals in their syllabi. Mike Reese, Associate Dean and Director of the Center for Educational Resources (CER), and Richard Shingles, a lecturer in Biology and Pedagogy Specialist in the CER, and created an Innovative Instructor print series article as an aid, shared below. If you are looking for other information on creating effective syllabi, type syllabus in the search box for this blog to see previous articles on the topic. Another resource for writing course learning goals is Arizona State University’s free Online Objectives Builder. It runs instructors through a logical process for creating course goals and objectives. Take the short tutorial and you are on your way.

What are course learning goals and why do they matter?

Effective teaching starts with thoughtful course planning. The first step in preparing a course is to clearly define your course learning goals. These goals describe the broad, overarching expectations of what students should be able to do by the end of the course, specifically what knowledge students should possess and/or what skills they should be able to demonstrate. Instructors use goals to design course assignments and assessments, and to determine what teaching methods will work best to achieve the desired outcomes.

Course learning goals are important for several reasons. They communicate the instructor’s expectations to students on the syllabus. They guide the instructor’s selection of appropriate teaching approaches, resources, and assignments. Learning goals inform colleagues who are teaching related or dependent courses. Similarly, departments can use them to map the curriculum. Departmental reviews of the learning goals ensure prerequisite courses teach the skills necessary for subsequent courses, and that multiple courses are not unnecessarily teaching redundant skills.

Once defined, the overarching course learning goals should inform the class-specific topics and teaching methods. Consider an example goal: At the end of the course, students will be able to apply social science data collection and analysis techniques. Several course sessions or units will be needed to teach students the knowledge and skills necessary to meet this goal. One class session might teach students how to design a survey; another could teach them how to conduct a research interview.

A syllabus usually includes a learning goals section that begins with a statement such as, “At the end of this course, students will be able to:” that is followed by 4-6 learning goals clearly defining the skills and knowledge students will be able to demonstrate.

Faculty should start with a general list of course learning goals and then refine the list to make the goals more specific. Edit the goals by taking into consideration the different abilities, interests, and expectations of your students and the amount of time available for class instruction. How many goals can your students accomplish over the length of the course? Consider including non-content goals such as skills that are important in the field.

Content goal: Analyze the key forces that influenced the rise of Japan as an economic superpower.

Non-content goal: Conduct a literature search.

The following list characterizes clearly-defined learning goals. Consider these suggestions when drafting goals.

Specific – Concise, well-defined statements of what students will be able to do.

Measurable – The goals suggest how students will be assessed. Use action verbs that can be observed through a test, homework, or project (e.g., define, apply, propose).

Non-measurable goal: Students will understand Maxwell’s Equations.

Measurable goal: Students will be able to apply the full set of Maxwell’s Equations to different events/situations.

Attainable – Students have the pre-requisite knowledge and skills and the course is long enought that students can achieve the goals.

Relevant – The skills or knowledge described are appropriate for the course or the program in which the course is embedded.

Time-bound – State when students should be able to demonstrate the skill (end of the course, end of semester, etc.).

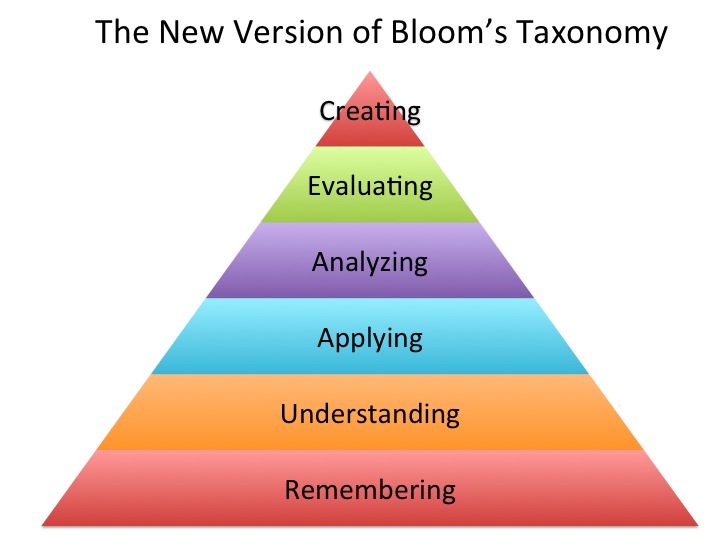

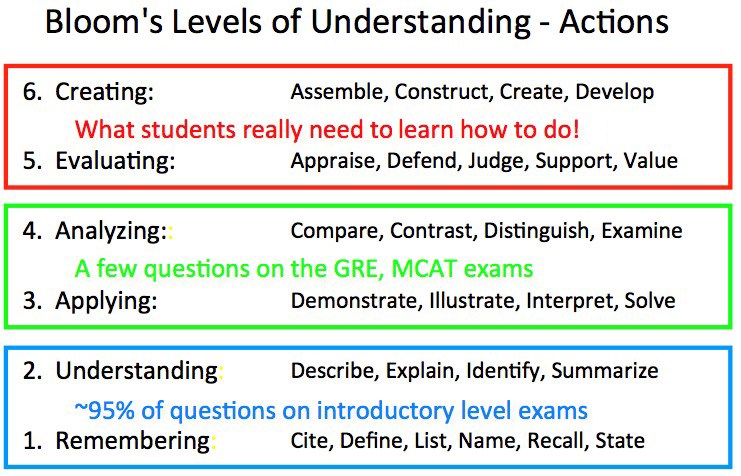

The most difficult aspect of writing learning goals for most instructors is ensuring the goals are measurable and attainable. In an introductory science course, students may be expected to recall or describe basic facts and concepts. In a senior humanities course, students may be expected to conduct deep critical analysis and synthesis of themes and concepts. There are numerous aids online that suggest action verbs to use when writing learning goals that are measurable and achievable. These aids are typically structured by Bloom’s Taxonomy – a framework for categorizing educational goals by their challenge level. Below is an example of action verbs aligned with Bloom’s Taxonomy.

Avoid vague verbs like “understand” or “know” because it can be difficult to come to consensus about how the goal can be measured. Think more specifically about what students should be able to demonstrate.

Here are examples of learning goals for several different disciplines using a common introductory statement. “By the end of this course, students will be able to do the following…

“Propose a cognitive neuroscience experiment that justifies the choice of question, experimental method and explains the logic of the proposed approach.” (Cognitive Science)

“Articulate specific connections between texts and historical, cultural, artistic, social and political contexts.” (German and Romance Languages and Literature)

“Design and conduct experiments.” (Chemistry)

“Design a system to meet desired needs within realistic constraints such as economic, environmental, social, political, ethical, health and safety, manufacturability, and sustainability.” (Biomedical Engineering)

Additional Resources

Bloom’s Taxonomy article. http://cer.jhu.edu/files/InnovInstruct-BP_blooms-taxonomy-action-speakslouder.pdf

Blog post on preparing a syllabus. http://ii.library.jhu.edu/2017/02/23/lunch-and-learn-constructing-acomprehensive-syllabus

Authors

Richard Shingles, Lecturer, Biology Department, JHU

Dr. Richard Shingles is a faculty member in the Biology department and also works with the Center for Educational Resources at Johns Hopkins University. He is the Director of the TA Training Institute and The Teaching Institute at JHU. Dr. Shingles also provides pedagogical and technological support to instructional faculty, postdocs and graduate students.

Michael J. Reese Jr., Associate Dean and Director, CER

Mike Reese is Associate Dean of University Libraries and Director of the Center for Educational Resources. He has a PhD from the Department of Sociology at Johns Hopkins University.

Images source: © 2017 Reid Sczerba, Center for Educational Resources