On Thursday, February 28, the Center for Educational Resources (CER) hosted the third Lunch and Learn for the 2018-2019 academic year. Rebecca Kelly, Associate Teaching Professor, Earth and Planetary Sciences and Director of the Environmental Science and Studies Program, and Pedro Julian, Associate Professor, Electrical and Computer Engineering, presented on Innovative Grading Strategies.

On Thursday, February 28, the Center for Educational Resources (CER) hosted the third Lunch and Learn for the 2018-2019 academic year. Rebecca Kelly, Associate Teaching Professor, Earth and Planetary Sciences and Director of the Environmental Science and Studies Program, and Pedro Julian, Associate Professor, Electrical and Computer Engineering, presented on Innovative Grading Strategies.

Rebecca Kelly began the presentation by discussing some of the problems in traditional grading. There is a general lack of clarity in what grades actually mean and how differently they are viewed by students and faculty. Faculty use grades to elicit certain behaviors from students, but it doesn’t necessarily mean that they are learning. Kelly noted that students, especially those at JHU, tend to be focused on the grade itself, aiming for a specific number and not the learning; this often results in high levels of student anxiety, something she sees often. She explained how students here don’t get many chances to fail and not have their grades negatively affected. Therefore, every assessment is a source of stress because it counts toward their grade. There are too few opportunities for students to learn from their mistakes.

Kelly mentioned additional challenges that faculty face when grading: it is often time consuming, energy draining, and stressful, especially when haggling over points, for example. She makes an effort to provide clearly stated learning goals and rubrics for each assignment, which do help, but are not always enough to ease the burden.

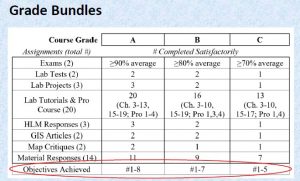

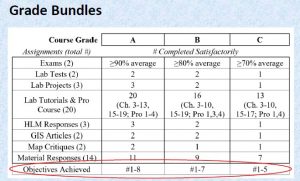

Kelly introduced the audience to specifications grading and described how she’s recently started using this approach in Introduction to Geographic Information Systems (GIS). With specifications grading (also described in a recent CER Innovative Instructor article), students are graded pass/fail or satisfactory/unsatisfactory on individual assessments that align directly with learning goals. Course grades are determined by the number of learning goals mastered. This is measured by the number of assessments passed. For example, passing 20 or more assignments out of 23 would equate to an A; 17-19 assignments would equate to a B. Kelly stresses the importance of maintaining high standards; for rigor, the threshold for passing should be a B or better.

In Kelly’s class, students have multiple opportunities to achieve their goals. Each student receives three tokens that he/she can use to re-do an assignment that doesn’t pass, or select a different assignment altogether from the ‘bundle’ of assignments available. Kelly noted the tendency of students to ‘hoard’ their tokens and how it actually works out favorably; instead of risking having to use a token, students often seek out her feedback before turning anything in.

Introduction to GIS has both a lecture and a lab component. The lab requires students to use software to create maps that are then used to perform data analysis. The very specific nature of the assignments in this class lend themselves well to the specifications grading approach. Kelly noted that students are somewhat anxious about this approach at first, but settle into it once they fully understand. In addition to clearly laying out  expectations, Kelly lists the learning goals of the course and how they align with each assignment (see slides). She also provides students with a table showing the bundles of assignments required to reach final course grades. Additionally, she distributes a pacing guide to help students avoid procrastination.

expectations, Kelly lists the learning goals of the course and how they align with each assignment (see slides). She also provides students with a table showing the bundles of assignments required to reach final course grades. Additionally, she distributes a pacing guide to help students avoid procrastination.

The results that Kelly has experienced with specifications grading have been positive. Students generally like it because the expectations are very clear and initial failure does not count against them; there are multiple opportunities to succeed. Grading is quick and easy because of the pass/fail system; if something doesn’t meet the requirements, it is simply marked unsatisfactory. The quality of student work is high because there is no credit for sloppy work. Kelly acknowledged that specifications grading is not ideal for all courses, but feels the grade earned in her GIS course is a true representation of the student’s skill level in GIS.

Pedro Julian described a different grading practice that he is using, something he calls the “extra grade approach.” He currently uses this approach in Digital Systems Fundamentals, a hands-on design course for freshmen. In this course, Julian uses a typical grading scale: 20% for the midterm, 40% for labs and homework, and 40% for the final project. However, he augments the scale by offering another 20% if students agree to put in extra work throughout the semester. How much extra work? Students must commit to working collaboratively with instructors (and other students seeking the 20% credit) for one hour or more per week on an additional project. This year, the project is to build a vending machine. Past projects include building an elevator out of Legos and building a robot that followed a specific path on the floor.

Julian described how motivated students are to complete the extra project once they commit to putting in the time. Students quickly realize that they learn all sorts of skills they would not have otherwise learned and are very proud and engaged. Student participation in the “extra grade” option has grown steadily since Julian started using this approach three years ago. The first year there were 5-10 students who signed up, and this year there are 30. Julian showed histograms (see slides) of student grades from past semesters in his class and how the extra grade has helped push overall grades higher. The histograms also show that it’s not just students who may be struggling with the class who are choosing to participate in the extra grade, but “A students” as well.

Similar to Rebecca Kelly’s experience, Julian expressed how grade-focused JHU students are, much to his dismay. In an attempt to take some of the pressure off, he described how he repeatedly tells his students that if they work hard, they will get a good grade; he even includes this phrase in his syllabus. Julian explained how he truly wants students to concentrate more on the learning and not on the grade, which is his motivation behind the “extra grade” approach.

An interesting discussion with several questions from the audience followed the presentations. Below are some of the questions asked and responses given by Kelly and Julian, as well as audience members.

Q: (for Julian) Some students may not have the time or flexibility in their schedule to take part in an extra project. Do you have suggestions for them? Did you consider this when creating the “extra grade” option?

Julian responded that in his experience, freshmen seem to be available. Many of them make time to come in on the weekends. He wants students to know he’s giving them an “escape route,” a way for them to make up their grade, and they seem to find the time to make it happen. Julian has never had a student come to him saying he/she cannot participate because of scheduling conflicts.

Q: How has grade distribution changed?

Kelly remarked how motivated the students are and therefore she had no Cs, very few Bs, and the rest As this past semester. She expressed how important it is to make sure that the A is attainable for students. She feels confident that she’s had enough experience to know what counts as an A. Every student can do it, the question is, will they?

Q: (for Kelly) Would there ever be a scenario where students would do the last half of the goals and skip the first half?

Kelly responded that she has never seen anyone jump over everything and that it makes more sense to work sequentially.

Q: (for Kelly) Is there detailed feedback provided when students fail an assignment?

Kelly commented that it depends on the assignment, but if students don’t follow the directions, that’s the feedback – to follow the directions. If it’s a project, Kelly will meet with the student, go over the assignment, and provide immediate feedback. She noted that she finds oral feedback much more effective than written feedback.

Q: (for Kelly) Could specs grading be applied in online classes?

Kelly responded that she thinks this approach could definitely be used in online classes, as long as feedback could be provided effectively. She also stressed the need for rubrics, examples, and clear goals.

Q: Has anyone tried measuring individual learning gains within a class? What skills are students coming in with? Are we actually measuring gain?

Kelly commented that specifications grading works as a compliment to competency based grading, which focuses on measuring gains in very specific skills.

Julian commented that this issue comes up in his class, students coming in with varying degrees of experience. He stated that this is another reason to offer the extra credit, to keep things interesting for those that want to move at a faster pace.

The discussion continued among presenters and audience members about what students are learning in a class vs. what they are bringing in with them. A point was raised that if students already know the material in a class, should they even be there? Another comment was made regarding if it is even an instructor’s place to determine what students already know. Additional comments were made about what grades mean and concerns about grades being used for different things, i.e. employers looking for specific skills, instructors writing recommendation letters, etc.

Q: Could these methods be used in group work?

Kelly responded that with specifications grading, you would have to find a way to evaluate the group. It might be possible to still score on an individual basis within the group, but it would depend on the goals. She mentioned peer evaluations as a possibility.

Julian stated that all grades are based on individual work in his class. He does use groups in a senior level class that he teaches, but students are still graded individually.

The event concluded with a discussion about how using “curve balls” – intentionally difficult questions designed to catch students off-guard – on exams can lead to challenging grading situations. For example, to ultimately solve a problem, students would need to first select the correct tools before beginning the solution process. Some faculty were in favor of including this type of question on exams, while others were not, noting the already high levels of exam stress. A suggestion was made to give students partial credit for the process even if they don’t end up with the correct answer. Another suggestion was to give an oral exam in order to hear the student’s thought process as he/she worked through the challenge. This would be another way for students to receive partial credit for their ideas and effort, even if the final answer was incorrect.

Amy Brusini, Senior Instructional Designer

Center for Educational Resources

Image Sources: Lunch and Learn Logo, slide from Kelly presentation

If you aren’t already using it, chances are you have probably heard of the online communication platform known as Slack. Slack is a cloud-based software program that is used for project management, information sharing, individual and group communication, as well as synchronous and asynchronous collaboration. There are free and paid plans available; the main difference between the plans is the number of messages that are accessible (10,000 with the free plan) and how many third-party tools are supported (10 with the free plan). What began in 2013 as a mode for inter-office conversation between two business offices has quickly expanded to hundreds of workplaces worldwide as well as many classrooms.

If you aren’t already using it, chances are you have probably heard of the online communication platform known as Slack. Slack is a cloud-based software program that is used for project management, information sharing, individual and group communication, as well as synchronous and asynchronous collaboration. There are free and paid plans available; the main difference between the plans is the number of messages that are accessible (10,000 with the free plan) and how many third-party tools are supported (10 with the free plan). What began in 2013 as a mode for inter-office conversation between two business offices has quickly expanded to hundreds of workplaces worldwide as well as many classrooms.

After 31 years at Johns Hopkins University, 11 in the Center for Educational Resources, six years and 198 posts on The Innovative Instructor, I am retiring. The good news is that my colleague, Amy Brusini, will be taking on the mantle, not only as the new editor of this blog, but as the Senior Instructional Designer in the CER.

After 31 years at Johns Hopkins University, 11 in the Center for Educational Resources, six years and 198 posts on The Innovative Instructor, I am retiring. The good news is that my colleague, Amy Brusini, will be taking on the mantle, not only as the new editor of this blog, but as the Senior Instructional Designer in the CER. While tracking down some resources for active learning this past week, I stumbled on

While tracking down some resources for active learning this past week, I stumbled on  The following post describes Omeka, a Web-based exhibition software application, and the how it was selected, installed on a local server, and is currently used at Johns Hopkins. Outside of Johns Hopkins these processes may serve as models. Alternatives to local hosting of Omeka are also outlined.

The following post describes Omeka, a Web-based exhibition software application, and the how it was selected, installed on a local server, and is currently used at Johns Hopkins. Outside of Johns Hopkins these processes may serve as models. Alternatives to local hosting of Omeka are also outlined.