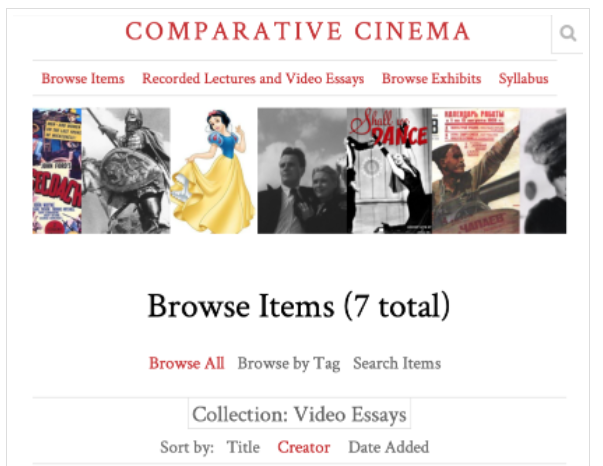

Since the death of the DVD player, several challenges have emerged for media-based courses: How can we give students access to a wide range of audiovisual, image, and text sources located on multiple different online platforms? What is the most efficient way for the instructor to access these materials in class spontaneously, and for students to be able to work with the materials on their own? Can we do this in a way that allows for critical engagement and sparks new associations? Can we make that engagement interactive? To address these challenges, graduate fellow Hale Sirin and I discovered Omeka, an open-source exhibition software tool developed at George Mason University. We found the Omeka platform optimal for creating media-rich digital collections and exhibitions.

In Fall 2019, funded by a Center for Teaching Excellence and Innovation (CTEI) Technology Fellowship Grant, we created and customized an instance of Omeka with the specific goal of designing a web-based environment to teach comparative cinema courses. We implemented the Omeka site in Spring 2020 for the course “Cinema of the 1930s: Communist and Capitalist Fantasies,” further supported by a CTEI Teaching Innovation Grant. This course compares films of the era in a variety of genres (musical, epic, Western, drama) from different countries, examining the intersections between politics and aesthetics as well as the lasting implications of the films themselves in light of theoretical works on film as a medium, ethics and gender. We adapted the online publishing software package into an interactive media platform on which the students could watch the assigned films, post comments with timestamps, and help expand the platform by sharing their own video essays. We built this platform with sustainability in mind, choosing open-source software with no recurring costs so that it could be used over the years and serve as a model for future interdisciplinary and comparative film and media courses.

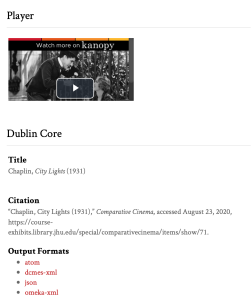

When building this website, our first task was to organize the digital archive of film clips and film stills for the course. These materials were then uploaded to Panopto, the online streaming service used by JHU, and embedded in the Omeka site. We also embedded the films that were publicly available on YouTube, Kanopy, and other archives, such as the online film archive of the production studio Mosfil’m, designing the Omeka site to serve as a single platform to stream this content. Each film, clip, text, or image was tagged with multiple identifiers to allow students to navigate the many resources for the course via search and sort functions, tags and hyperlinks, creating an interactive and rich learning environment. We added further functionality to the website by customizing interactive plugins, such as the “Comments” function, which allowed us to create a thread for each film in which students could respond to the specific prompts for the week and to timestamp the specific parts of the film to which their comments referred.

We also embedded the films that were publicly available on YouTube, Kanopy, and other archives, such as the online film archive of the production studio Mosfil’m, designing the Omeka site to serve as a single platform to stream this content. Each film, clip, text, or image was tagged with multiple identifiers to allow students to navigate the many resources for the course via search and sort functions, tags and hyperlinks, creating an interactive and rich learning environment. We added further functionality to the website by customizing interactive plugins, such as the “Comments” function, which allowed us to create a thread for each film in which students could respond to the specific prompts for the week and to timestamp the specific parts of the film to which their comments referred.

In order to abide by copyright laws, only films in the public domain were streamed in their entirety. For other films, we provided selected short clips on Omeka, which we were able to easily access during class. Students were able to access the films available on Kanopy through our website by entering their JHU credentials.

Teaching comparative cinema with the interactive website powered by Omeka provided the students with a novel way of accessing comparative research in film studies. The website served as a single platform, interconnecting the digital material (video, image and text) and creating an interactive and rich learning environment to enhance student learning both in and outside of class time. Rather than the materials being fixed to the syllabus week to week, students could search film clips by director, year, country, or theme. Students were thus able to compare and contrast many images and films from across cultural divides on a unified online platform.

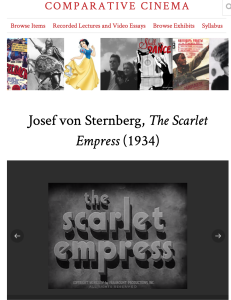

Students were not only able to access the course materials on the Omeka site, but also to expand and re-structure the content.  Over the course of the semester, students contributed to the annotation of film clips by uploading their comments to the films and timestamping important sequences. Since they were also required to draw their presentations from material in the exhibition, their engagement on the site was quantifiable on an on-going basis. As their final projects, they had the option of creating a video essay, which involved editing together clips from the films, and recording an interpretive essay over them, like a commentary track. Their video essays were shared with their peers on the Omeka site.

Over the course of the semester, students contributed to the annotation of film clips by uploading their comments to the films and timestamping important sequences. Since they were also required to draw their presentations from material in the exhibition, their engagement on the site was quantifiable on an on-going basis. As their final projects, they had the option of creating a video essay, which involved editing together clips from the films, and recording an interpretive essay over them, like a commentary track. Their video essays were shared with their peers on the Omeka site.

After switching to online learning in Spring 2020 due to Covid19, the Omeka site not only performed its original task, but was flexible enough to give us the opportunity to build an asynchronous, alternative educational environment, now not only hosting the course materials and discussion forums, but also the weekly recorded lectures, recordings of our Zoom discussion sessions, and students’ final video essays.

We thank the Center for Teaching Excellence and Innovation (previously known as the Center for Educational Resources) and the Sheridan Libraries for their support and continual guidance during this project.

Additional Resources:

https://blogs.library.jhu.edu/2016/08/omeka-for-instruction/

Authors’ Backgrounds:

Anne Eakin Moss was an Assistant Professor in JHU’s Department of Comparative Thought and Literature, a board member of the program in Women, Gender, and Sexuality and of the Center for Advanced Media Studies. She was the 2017 recipient of the KSAS Excellence in Graduate Teaching/Mentorship Award and a Mellon Arts Innovation Grant, and a 2019 KSAS Discovery Award winner. Since the fall of 2021, she has been at the University of Chicago where she is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Slavic Languages & Literatures.

Hale Sirin is a Ph.D. Candidate in the Department of Comparative Thought and Literature. A recipient of the Dean’s Teaching Fellowship and the Women, Gender, and Sexuality teaching fellowship, she has taught courses in comparative literature, philosophy, and intellectual history. Her research interests include early 20th-century philosophy and literature, theories of representation and media in modernity, and digital humanities.

Image source: Hale Sirin