[Guest post by Scott Smith, Professor, Computer Science, Johns Hopkins University]

Grading can be one of the most time consuming and tedious aspects of teaching a course, but it’s important to give prompt and meaningful feedback to your students. In large courses, aligning grading practices across multiple teaching assistants (TAs) necessitates a level of coordination that includes scheduling grading meetings, reviewing materials for correct answers, and calibrating point evaluations, all of which can take up valuable time during the semester.

Grading can be one of the most time consuming and tedious aspects of teaching a course, but it’s important to give prompt and meaningful feedback to your students. In large courses, aligning grading practices across multiple teaching assistants (TAs) necessitates a level of coordination that includes scheduling grading meetings, reviewing materials for correct answers, and calibrating point evaluations, all of which can take up valuable time during the semester.

In courses that teach programming, we typically assign students projects that require them to write programs to solve problems. When instructors grade this type of assignment, they not only have to observe the program’s results but also the student’s approach. If the results are not correct or the program doesn’t run, we have to spend time reviewing hundreds of lines of code to debug the program to give thoughtful feedback.

In the past, my method for grading assignments with my TAs may have been arduous but it worked. However, last year, no TAs were assigned to my Principles of Programming Languages course. Concerned that I wouldn’t have enough time to do all the work, I looked for another solution.

Consistent grading and providing meaningful feedback for student’s every submission, especially with multiple teaching assistants (TAs) can be challenging. Typically, when grading, I would schedule a time to sit down with all of my TAs, review the assignment or exam, give each TA a set of questions to grade, pass the submissions around until all were graded, and finally calculate the grades. When a TA had a question, we could address it as a group and make the related adjustments throughout the submissions as needed. While this system worked, it was tedious and time consuming. Occasionally, inconsistencies in the grades came up, which could prompt regrade requests from students. I kept thinking that there had to be a better way.

About year and a half ago, a colleague introduced me to an application called Gradescope to manage the grading of assignments and exams. I spent a relatively short amount of time getting familiar with the application and used it in a course in the fall of 2016, for both student-submitted homework assignments and in-class paper exams. In the case of the homework, students would upload a digital version of the assignment to Gradescope. The application would then prompt the student to designate the areas in the document where their answers can be found so that the application could sort and organize the submissions for the ease of grading. For the in-class exams, I would have the students work on a paper-based exam that I set up in Gradescope with the question areas established. I then would scan and upload the exams so that Gradescope could associate the established question areas to the student submissions automatically. The process of digitizing the completed tests and correlating them to the class roster was made easy with a scanner and Gradescope’s automatic roster matching feature. Gradescope became a centralized location where my TAs and I could grade student work.

There are a few ways to consider incorporating Gradescope into your course. Here is a non-exhaustive list of scenarios for both assignments and exams that can be accommodated:

- Handwritten/drawn homework (students scan them and upload the images/PDFs)

- Electronic written homework (students upload PDFs)

- In-class exams (instructor scans them and uploads the PDFs)

- Coding scripts for programming assignment (students upload their program’s files for auto-grading)

- Code assignments graded by hand (students upload PDFs of code)

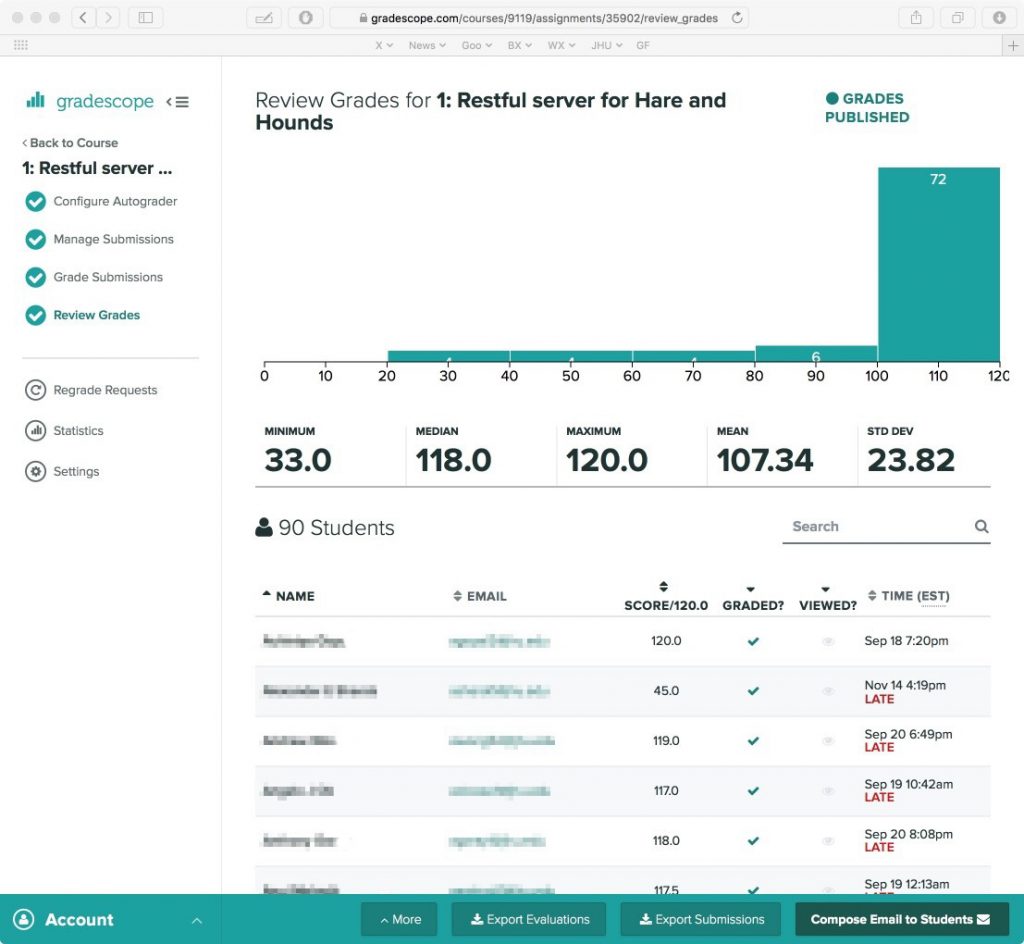

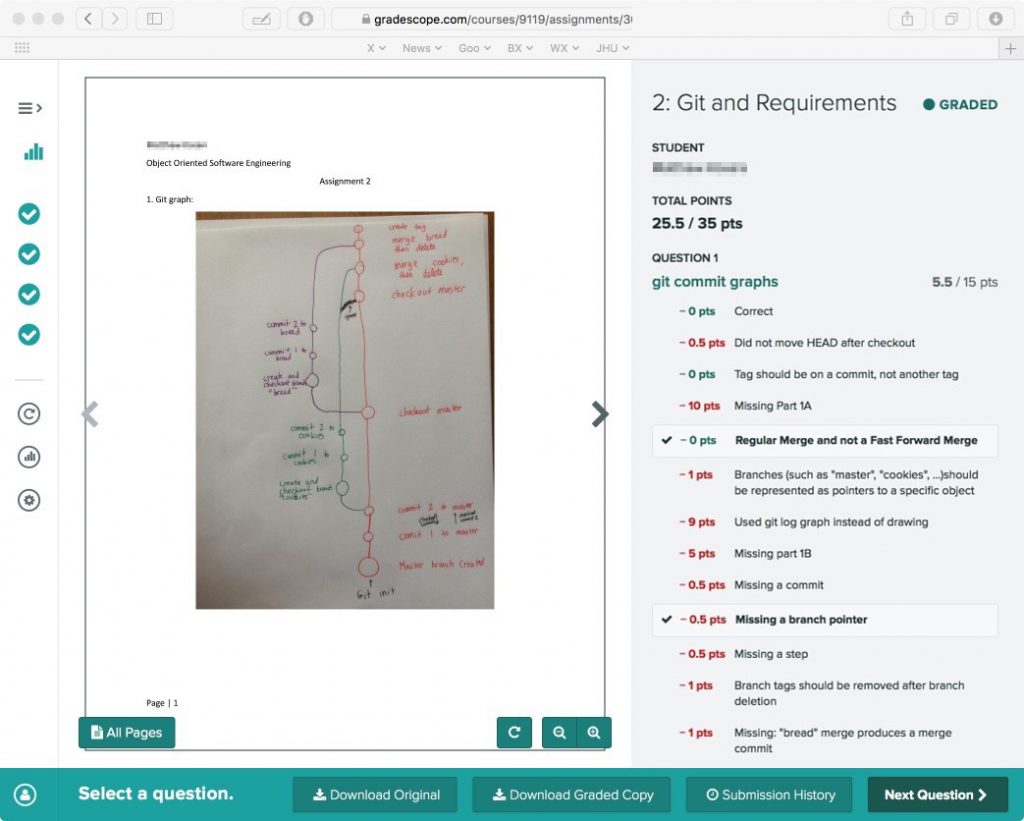

The real power of Gradescope is that it requires setting up a reusable rubric (a list of competencies or qualities used to assess correct answers) to grade each question. When grading, you select from or add to the rubric to add or deduct points. This keeps the grading consistent across multiple submissions. As the rubric is established as a part of the assignment, you can also update the point values at any time if you later determine that a larger point addition/deduction is advisable, and the grade calculations will update automatically.

Screenshot of Gradescope’s Review Grade for an assignment

After being informed that I wouldn’t have any TAs for my Principles of Programming Languages course the following semester, I was motivated to use one of Gradescope’s [features, the programming assignment auto-grader platform. Being able to automatically provide grades and feedback for students’ submitted code has long been a dream of instructors who teach programming. Gradescope offers a language-agnostic environment in which the instructor sets up the components and libraries needed for the students’ programs to run. The instructor establishes a grading script that is the basis for the analysis, providing grades and feedback for issues found in each student’s submitted program.

Overall, the use of Gradescope has reduced time spent grading and improves the quality of feedback that I am able to provide students. For instance, when I release grades to the students, they are able to review each of the descriptive rubrics that were used when grading their submissions, as well as any additional comments. Auto-grader was really the star feature in this case. Students were able to submit their code, determine if it would run, and make corrections before the deadline to increase their chances of a better grade. There are features to reduce the number of allowed submissions, but I choose not to set a limit so that the students could use an iterative approach to getting the right solution.

Gradescope is only effective if your rubrics and grading criteria are well thought out, and the auto-grading scripts require some time to set up. Creating the grading scripts for the programming assignments may seem time intensive, but by frontloading the work with detailed rubrics and test cases, more time is saved in the grading process. The value of this preparation scales as enrollment increases, and the rubrics and scripts can be reused when you teach the course again. With more time during the semester freed up by streamlining the grading process, my TAs and I were able to increase office hours, which is more beneficial in the long run for the students.

Student’s submission with rubric items used in grading

The process for regrading is much easier for both students and instructors. Before Gradescope, a regrade request meant determining which TA graded that question, discussing the request with them, and then potentially adjusting the grade. With the regrade feature, students submit a regrade request, which gets routed to that question’s grader (me or the TA) with comments for the grader to consider. The grader can then award the regrade points directly to the student’s assignment. As the instructor, I can see all regrade requests, and can override if necessary, which helps to reduce the bureaucracy and logistics involved with manual regrading. Additionally, regrade requests and Gradescope’s assignment statistics feature may allow you to pinpoint issues with a particular question or how well students have understood a topic.

I have found that when preparing assignments with Gradescope, I am more willing to create multiple mini-assignments. With large courses, the tendency would be to create fewer assignments that are larger in scope to lessen the amount of grading. When there are too few submission points for students who are deadline oriented, I find that they wait till the last few days to start the assignment, which can make the learning process less effective. By adding more assignments, I can scaffold the learning to incrementally build on topics taught in class.

After using Gradescope for a year, I realized that it could be used to detect cheating. Gradescope allows you to see submissions to specific questions in sequence, making it easy to spot submissions that are identical, a red-flag for copied answers. While not a feature, it is an undocumented bonus. It should also be noted that Gradescope adheres to FERPA (Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act) standards for educational tools.

Additional Resources:

- Gradescope website: https://gradescope.com

- NOTE TO JHU READERS ONLY: The institutional version of Gradescope is currently available to JHU faculty users through a pilot program. If you are faculty at Johns Hopkins University’s Homewood campus interested in learning more about how Gradescope might work for your courses, contact Reid Sczerba in the Center for Educational Resources at rsczerb1@jhu.edu.

Scott Smith, Professor

Department of Computer Science, Johns Hopkins University

Scott Smith has been a professor of Computer Science at Hopkins for almost 30 years. His research specialty is programming languages. For the past several years, he has taught two main courses, Software Engineering, a 100 student project-based class, and Principles of Programming Languages, a mathematically-oriented course with both written and small programming assignments.

Images Sources: CC Reid Sczerba, Gradescope screenshots courtesy Scott Smith