Back at the beginning of the year I wrote a post on Scalar (a multi-media authoring tool) that mentioned another application called Easel.ly. I’d first heard about Easel.ly from a colleague last fall and have been wanting to try it out ever since. This week, I got my chance and I am really excited about this application.

Anita Say Chan and Harriett Green wrote about Easel.ly in an article published in the Educause Review, Practicing Collaborative Digital Pedagogy to Foster Digital Literacies in Humanities Classrooms (October 13, 2014). Their description captures the essence of the tool:

Anita Say Chan and Harriett Green wrote about Easel.ly in an article published in the Educause Review, Practicing Collaborative Digital Pedagogy to Foster Digital Literacies in Humanities Classrooms (October 13, 2014). Their description captures the essence of the tool:

“Easel.ly is a free, easy-to-use web-hosted platform for creating infographics. Users can insert icons and shapes, change background and orientation, and rearrange the pre-inserted graphics in the pre-set template (called a “vheme”) to create their own vibrant infographics.

We chose this tool because its features let students rapidly build professional, visually captivating infographics in a user-friendly environment without requiring mastery of graphic imaging software (such as Adobe Photoshop or Illustrator).”

The term infographic has a broad meaning – a visual depiction of information – and the end results of an Easel.ly creation cover a wide range as can be seen from the hundreds of thousands of posted examples. Timelines, annotated maps, flowcharts, posters, public service announcements, instructional guides – if you are thinking in terms of a course assignment that will involve visualization or visual display of data/information – take a look at Easel.ly. Easel.ly also has a feature that allows you to create groups to work collaboratively. See creating groups: http://www.easel.ly/blog/easel-ly-groups-new-feature/. This would be a great way to allow students to work together on a course project.

It’s easy to create an account and start to work. The interface is simple and intuitive. You can start with a blank canvas, pick a template (vheme), or select from thousands of published examples to modify. From there it is a breeze to drag and drop from menus that include backgrounds, objects (images, icons, maps, flags), text boxes, shapes and arrows, and charts. All of these can be easily modified (size, orientation, font, color in some cases). You can also upload your own images, icons, maps, graphs, etc.

Once you have completed your work there are several ways to make it available to others. According to the Easel.ly blog post on sharing options:

Shareable Link: A shareable link allows a user to both See and Reuse your infographic – The only people that can see and reuse the infographic are people who you give the link to.

Embed Code: If you would rather embed your infographic within a blog post and not have to download and upload to your blog, then “Embed Code” is the way to go.

Group Share: Probably our coolest feature. This option allows you to share an infographic that you have created with everyone in your group (see here: Creating a Group) and allow them to reuse your infographic as a template for their work.

If you want more information on using Easel.ly, take a look at the blog. If you’d like more features, there is a paid version available for only $36.00 per year.

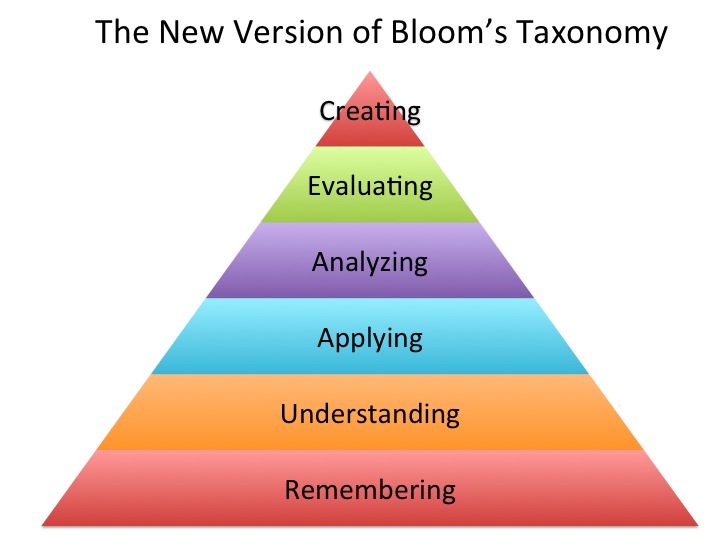

I opened a free account on Easel.ly and within an hour had tried out all of the features and created the infographic that accompanies this post. The About Us section of the Easel.ly website summed up my experience:

“…[I]n 2013 Easel.ly was honored to receive the Best Websites for Teaching and Learning Award from the American Association of School Librarians (AASL). The AASL commended Easel.ly for being user friendly, intuitive, and simple enough that even a child in the 6th grade could successfully navigate the site and design their infographic without adult assistance.”

Macie Hall, Senior Instructional Designer

Center for Educational Resources

Image Source: Infographic created by Macie Hall on Easel.ly