On Tuesday, October 15, the Center for Educational Resources (CER) hosted the first Lunch and Learn—Faculty Conversations on Teaching—for the 201-2018 academic year. Sanchita Balachandran, Associate Director, the Johns Hopkins Archaeological Museum and Senior Lecturer, Department of Near Eastern Studies; and Sauleh Siddiqui, Assistant Professor, Civil Engineering presented on their experiences using authentic assignments.

On Tuesday, October 15, the Center for Educational Resources (CER) hosted the first Lunch and Learn—Faculty Conversations on Teaching—for the 201-2018 academic year. Sanchita Balachandran, Associate Director, the Johns Hopkins Archaeological Museum and Senior Lecturer, Department of Near Eastern Studies; and Sauleh Siddiqui, Assistant Professor, Civil Engineering presented on their experiences using authentic assignments.

As a preface, students often ask why they need to learn something, and wonder when, if ever, they will use course information. Authentic assignments give students “real-world” experience and context, and involve hands-on, active learning.

Sanchita Balachandran is Associate Director and conservator of the JHU Archaeological Museum as well as a lecturer in the Department of Near Eastern Studies. The collection was started in 1882, just six years after the founding of the University, and now occupies a jewel-box of a space in the renovated Gilman Hall, where its collection is at long last appropriately displayed. Balachandran uses the museum collection and “teaches courses related to the identification and analysis of ancient manufacturing techniques of objects, as well as the history, ethics and practice of museum conservation and curation.” She’s long been interested in authentic learning, and has recently taught two courses that exemplify this method: Recreating Ancient Greek Ceramics and Roman Egyptian Mummy Portraits. [See presentation slides.]

Sanchita Balachandran is Associate Director and conservator of the JHU Archaeological Museum as well as a lecturer in the Department of Near Eastern Studies. The collection was started in 1882, just six years after the founding of the University, and now occupies a jewel-box of a space in the renovated Gilman Hall, where its collection is at long last appropriately displayed. Balachandran uses the museum collection and “teaches courses related to the identification and analysis of ancient manufacturing techniques of objects, as well as the history, ethics and practice of museum conservation and curation.” She’s long been interested in authentic learning, and has recently taught two courses that exemplify this method: Recreating Ancient Greek Ceramics and Roman Egyptian Mummy Portraits. [See presentation slides.]

When designing authentic learning assignments Balachandran asks herself a series of questions.

- Is this a question I am genuinely curious about and don’t know the answer to? With the course on recreating Greek ceramics she had long wondered how these objects were made (a subject of speculation and debate but no definitive answers). For both Balachandran and her students, it was both “exhilarating and terrifying” to not know what the end results would be. They would be discovering the answers together and this was motivating for the students.

- Is the question big enough, and are the stakes high? For her course on Roman Egyptian mummy portraits (Freshman Seminar: Technical Research on Archaeological Objects in the Johns Hopkins Archaeological Museum) the primary goal was to generate and collect technical data on these ancient portraits for contribution to an international data base. Other collaborators included the J. Paul Getty Museum, the British Museum, the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, the Walters Art Museum and the Art Institute of Chicago. The students were working with “big players” in the museum world.

- Do I have a physical thing that can be the focus of sustained and weekly examination and research? In both courses museum artifacts provided a focus point for the students.

- What methodology am I trying to teach? Balachandran’s methodology involved working hands-on with museum objects, consulting with experts and specialists in the field, documenting through writing, photography, and film the processes, and sharing observations and reflections with a broad audience. She noted that it was important that students experience moments of confusion during the process as it teaches them to think critically about, for example, past research, and what applies and doesn’t.

- What kind of expertise is need and who has it and will help? Balachandran spends a great deal of time in advance of her courses identifying relevant resources. She noted the value of Skype for bringing subject matter experts and specialists into the classroom from around the world.

- Is my class of students disciplinarily diverse? Balachandran advertises her courses broadly. Museum work often involves material scientists, for example. Her Greek vase course had students from materials science, applied mathematics, and biomedical engineering as well as the humanities and social sciences.

- Is the class work challenging and is there a hands on component? In each of the courses, Balachandran had students working with the materials that were used in the creation of the original art objects. The students made vases from clay using the techniques known to have been used in Ancient Greece; in the portrait course, they painted with encaustic, the material used by Roman Egyptians. She stressed that this was more than an arts and crafts session. Students studied the material science behind the techniques that were used and gained an appreciation for how the works were created.

- Is there an enduring “deliverable” or a regular public component to the class? Students contributed to the international data base in the mummy portraits class and blogged regularly as a part of the Greek vases class. Balachandran used social media (Facebook) to publicize student work. There was also a documentary film—Mysteries of the Kylix—made during the class that has been viewed over 4000 times. She arranged for radio spots on WYPR (Baltimore’s NPR station) and gained exposure through Johns Hopkins publications and the Baltimore Sun newspaper.

- Do I see my students as collaborators? Balachandran makes sure that students are given credit in the public components of the course and regularly acknowledges their participation. She sees herself as in the trenches with the students, finding answers to problems together.

- Am I ready not to be in control of what we find out? This is perhaps the most difficult step for an instructor to take with authentic assignments, but the one that will allow for the real learning gains. We learn from our failures as well as successes, and that is important for students to experience firsthand.

In conclusion, Balachandran summarized what students learned during her courses:

- Everything is more complicated than we think and merits repeated examination/re-examination

- Our work in the classroom produces unique specialized knowledge

- We can participate in and contribute to scholarly conversations

- We should broaden our own knowledge base and collaborate beyond our usual networks

- We must provide access to the knowledge we produce

- The process of trying to answer a question is more important than answering the question—and will lead to more interesting questions

- We can/must ask more daring questions.

Siddiqui discussed the main components of authentic learning assignments as he uses them in his courses with the most important being that students should be doing rather than listening. [See presentation slides.] These are:

- The judgment to distinguish reliable from unreliable information.

- The patience to follow longer arguments.

- The synthetic ability to recognize relevant patterns in unfamiliar contexts.

- The flexibility to work across disciplinary and cultural boundaries to generate innovative solutions.

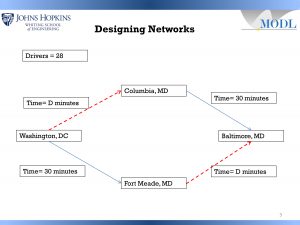

In his course, Equilibrium Models in Systems Engineering, students work on real-life examples such as designing transportation networks. To demonstrate an exercise that Siddiqui uses in his course, he passed out clickers to the audience, as his students would use. He then set up a problem involving getting from Washington, DC to Baltimore, MD using a combination of driving and taking a train, with two possible routes. Driving time on each route will vary depending on the number of cars on the road. The model is set for the number of participants/students in the group—if there are 28 participants driving on the same route, the driving part of the trip will take 28 minutes. If there are 5 participants driving on the route, it will take 5 minutes. The train trip is static and takes 30 minutes on each route. Using their clickers, participants vote on a route, A or B. Siddiqui then show the histogram of the vote, and participants can change their vote based on the road time component. As participants change votes, the driving time will increase or decrease on each choice. Voting continues until eventually a state of equilibrium is reached and the driving time on the two routes is equal.

In his course, Equilibrium Models in Systems Engineering, students work on real-life examples such as designing transportation networks. To demonstrate an exercise that Siddiqui uses in his course, he passed out clickers to the audience, as his students would use. He then set up a problem involving getting from Washington, DC to Baltimore, MD using a combination of driving and taking a train, with two possible routes. Driving time on each route will vary depending on the number of cars on the road. The model is set for the number of participants/students in the group—if there are 28 participants driving on the same route, the driving part of the trip will take 28 minutes. If there are 5 participants driving on the route, it will take 5 minutes. The train trip is static and takes 30 minutes on each route. Using their clickers, participants vote on a route, A or B. Siddiqui then show the histogram of the vote, and participants can change their vote based on the road time component. As participants change votes, the driving time will increase or decrease on each choice. Voting continues until eventually a state of equilibrium is reached and the driving time on the two routes is equal.

Siddiqui then throws in another component. What happens if you add another variable, a new road? Participants can now vote for three options. Ultimately his students will see (as did the participants at the Lunch and Learn) that sometimes a third option can worsen the situation rather than improve it.

In his classes, students work with actual examples taken from New York City, Germany, South Korea, and other places, to examine the factors that went into the design process, and analyze what went wrong. Siddiqui feels that engineers are not necessarily taught to work with real-life situations and this can lead to poor design. Engineers need to understand the factors that impact actual human decision making in order to build successful solutions.

In the discussion period that followed the presentation, Balachandran and Siddiqui agreed that students are motivated by working with real-life problems. Siddiqui noted that his students still had to “slog through” doing the mathematics behind the exercises, but valued understanding both sides.

In discussing how to gauge whether an assignment or project was too big or too small, it was agreed that it is important to scaffold larger projects, build support structures, and allow for flexibility. It was acknowledged that students will struggle with ambiguity. It is important with authentic assignments to be clear that the goal is not so much to find an answer as to go through a process.

Both presenters agreed that setting up these authentic learning experiences—assignments, projects, and courses, can be time consuming and challenging. But, for both, the benefits for students have been substantial and they will continue to explore the possibilities for future classes.

Macie Hall, Senior Instructional Designer

Center for Educational Resources

Image Sources: Lunch and Learn Logo, slides from Balachandran and Siddiqui presentations