On Friday, December 15, the Center for Educational Resources (CER) hosted the second Lunch and Learn—Faculty Conversations on Teaching—for the 2017-2018 academic year. Laura Foster, Academic Advisor, Public Health Studies, and Reid Mumford, Instructional Resource Advisor, Physics & Astronomy, presented on Creating Rubrics and Calibrating Multiple Graders.

On Friday, December 15, the Center for Educational Resources (CER) hosted the second Lunch and Learn—Faculty Conversations on Teaching—for the 2017-2018 academic year. Laura Foster, Academic Advisor, Public Health Studies, and Reid Mumford, Instructional Resource Advisor, Physics & Astronomy, presented on Creating Rubrics and Calibrating Multiple Graders.

Laura Foster led by giving us a demonstration of her use of Blackboard for creating rubrics. She noted that she might be “preaching to the choir” but hoped that those present might take back these best practices to their colleagues. Noting that many faculty have negative opinions of Blackboard, she put in a plug for its organizational benefits and facilitation of communication with students.

Foster started using Blackboard tools for a Public Health Studies class where she was grading student reflections. The subject matter—public health studies in the media—was outside of her field of physical chemistry. Blackboard facilitates creating a rubric that students can see when doing an assignment and the instructor then uses to grade that work. She showed the rubric detail that students see in Blackboard, and how the rubric can be used in grading. [See the CER Tutorial on Blackboard Rubrics and Rubrics-Helpful Hints] The rubric gives the students direction and assures that the instructor (or other graders) will apply the same standards across all student work.

It empowers students when they know exactly what criteria will be used in evaluating their work and how many points will be assigned to each component. Foster has found that using rubrics is an effective way to communicate assignment requirements to students, and that it helps her to clarify for herself what at the most important points. She noted that a rubric is very useful when there are multiple graders, such as Teaching Assistants (TAs), as it helps to calibrate the grading.

In response to questions from the audience, Foster stated that rubrics can be developed to cover both qualitative and quantitative elements. Developing good rubrics is an iterative process; it took her some time to sharpen her skills. There is flexibility in differentiating points allotted, but the instructor must be thoughtful, plan for a desired outcome, and communicate clearly. The rubric tool can be used to grade PDF files as well as Word documents. Foster noted that it is important to take opportunities to teach students to learn to write, learn to use technology, learn to read instructions, and learn to look at feedback given on assignments. Being transparent and explaining why you are using a particular technology will go a long way.

Reid Mumford gave his presentation on how he calibrates multiple graders (see slides). Mumford oversees the General Physics lab courses. This is a two semester, required sequence, so not all students are excited to be there. The sequences are on Mechanics and Electricity and Magnetism; both labs are taught every semester with multiple sections for each course. Approximately 600 to 700 students are taking these lab sequences each semester; students are divided into sections of about 24 students. The labs are open-ended and flexible, so students aren’t filling in blanks and checking boxes, which would be easier to grade. Lab sections are taught and graded by graduate student TAs, with about 30 TAs teaching each semester. Teaching and grading styles vary among these TAs as would be expected. Clearly, calibrating their grading is a challenge.

Grades are based on the best 9 of 10 lab activities, which consist of a pre-lab quiz and a lab note. All activities are graded using the same rubric. The grading scale used can be seen in the slides. One of the criteria for grading is “style,” which allows some flexibility and qualitative assessment. Students have access to the rubric, which is also shown in the slides.

About three years ago, Mumford adopted Turnitin (TII), the plagiarism detection tool, for  its efficient grading tools. It works well for his use because it is integrated with Blackboard. TII does its job in detecting cheating (and Mumford noted that lots of students are cheating), but it is the grading tools that are really important for the TAs. TAs are encouraged to be demanding in their grading and leave a lot of feedback, so grading takes them two to four hours each week. TII’s Feedback Studio (formerly known as GradeMark) allows TAs to accomplish their mission. [See CER tutorial on Feedback Studio and The Innovative Instructor post on GradeMark.] It was the QuickMark feature that sold Mumford on Feedback Studio and TII grading. Using the rubric for each activity, QuickMark can be pre-populated with commonly-used comments, which can then be dragged and dropped onto the student’s submitted work.

its efficient grading tools. It works well for his use because it is integrated with Blackboard. TII does its job in detecting cheating (and Mumford noted that lots of students are cheating), but it is the grading tools that are really important for the TAs. TAs are encouraged to be demanding in their grading and leave a lot of feedback, so grading takes them two to four hours each week. TII’s Feedback Studio (formerly known as GradeMark) allows TAs to accomplish their mission. [See CER tutorial on Feedback Studio and The Innovative Instructor post on GradeMark.] It was the QuickMark feature that sold Mumford on Feedback Studio and TII grading. Using the rubric for each activity, QuickMark can be pre-populated with commonly-used comments, which can then be dragged and dropped onto the student’s submitted work.

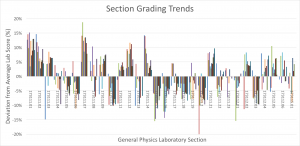

These tools helped make the grading load more efficient, but calibrating the multiple graders was another challenge. Mumford found that the TAs need lots of feedback on their grading. Each week he downloads all the grades from Blackboard grade centers. He creates a plot that shows the average score for the weekly lab assignment. Outliers to the average scores are identified and these TAs are counseled so that their grading can be brought into line. Mumford also looks at section grading trends and can see which sections are being graded more leniently or harshly than average. He works with those TAs to standardize their grading.

These tools helped make the grading load more efficient, but calibrating the multiple graders was another challenge. Mumford found that the TAs need lots of feedback on their grading. Each week he downloads all the grades from Blackboard grade centers. He creates a plot that shows the average score for the weekly lab assignment. Outliers to the average scores are identified and these TAs are counseled so that their grading can be brought into line. Mumford also looks at section grading trends and can see which sections are being graded more leniently or harshly than average. He works with those TAs to standardize their grading.

In calculating final grades for the course, Mumford keeps three points in mind: final letter grades must be calculated, there should be no “easy” or “hard” sections of lab, and distribution should not vary (significantly) between sections. He makes use of per-section mapping and uses average and standard deviation to map results to a final letter grade model. Mumford noted that students are made aware, repeatedly, of the model being used. He is very transparent—everything is explained in the syllabus and reiterated weekly in lab sessions.

In conclusion, Mumford offered these take-aways:

- Calibrating Multiple Graders is not easy

- Tools are needed to handle multiple sections efficiently

- Rubrics help but do not solve the calibration problem

- Regular feedback to graders is essential

- Limit of the system: student standing is ambiguous

In the future Mumford plans to give students a better understanding of course standing, to calculate a per-section curve each week, and to overcome some technical issues and the greater time investment that will be required with weekly calibrating and rescaling.

Macie Hall, Senior Instructional Designer

Center for Educational Resources

Image Sources: Lunch and Learn Logo, slides from Mumford presentation