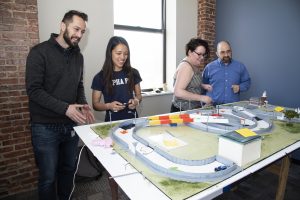

On Wednesday, April 19th, the Center for Teaching Excellence and Innovation (CTEI) hosted a Lunch and Learn on Community-Based Learning. Luisa De Guzman, Assistant Director of the Center for Social Concern, moderated a panel of faculty from the Engaged Scholar Faculty and Community Partner Fellows Program. Sponsored by the  Center for Social Concern, this program supports partnerships between JHU faculty and leaders from Baltimore City non-profits in co-teaching Community-Based Learning courses. The panel included: Anne-Elizabeth Brodsky, Associate Teaching Professor in the University Writing Program, Alissa Burkholder Murphy, Senior Lecturer in Mechanical Engineering, Jasmine Blanks Jones, Executive Director of the Center for Social Concern, Matthew Pavesich, Teaching Professor and Director of the University Writing Program, and Victoria Harms, Visiting Assistant Professor in History.

Center for Social Concern, this program supports partnerships between JHU faculty and leaders from Baltimore City non-profits in co-teaching Community-Based Learning courses. The panel included: Anne-Elizabeth Brodsky, Associate Teaching Professor in the University Writing Program, Alissa Burkholder Murphy, Senior Lecturer in Mechanical Engineering, Jasmine Blanks Jones, Executive Director of the Center for Social Concern, Matthew Pavesich, Teaching Professor and Director of the University Writing Program, and Victoria Harms, Visiting Assistant Professor in History.

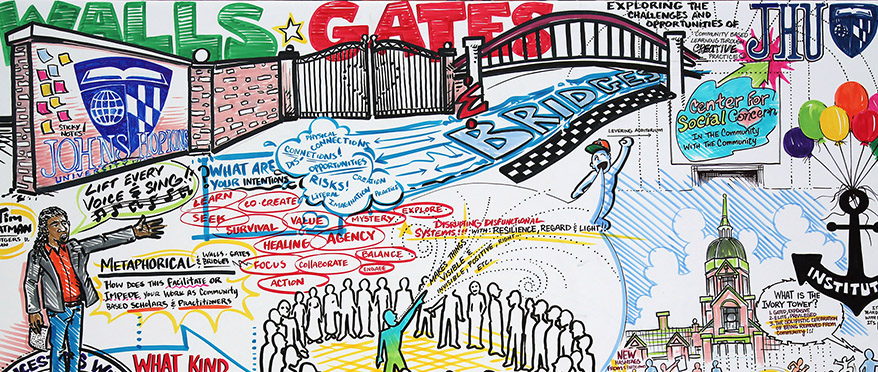

De Guzman opened the presentation by describing community-based learning (CBL) and the opportunities available at the Center for Social Concern. CBL is a pedagogical model that integrates student learning with community engagement. It provides students the opportunity to apply what they are learning in real-world settings and reflect on their service experiences within a classroom setting. By partnering with community organizations, students, faculty, and community stakeholders benefit from the collaborative experience of pursuing mutual goals (Kuh, 2008).

The Engaged Scholarship program at the Center for Social Concern offers various ways to encourage faculty to integrate CBL into their teaching; opportunities range from mini grants of $500 to support CBL activities to an award of up to $5000 with the Engaged Scholar Faculty Fellows program to develop CBL courses with partners in the community. The Spring 2023 Engaged Scholar Faculty Fellows on the panel taught the following courses:

- Anne Elizabeth Brodsky: Reintroduction to Writing: Music, Young People, and Democracy

- Alissa Burkholder Murphy: Social Impact Design

- Jasmine Blanks Jones: Black Storytelling: Public Health Education in the Black World

- Matthew Pavesich: Reintroduction to Writing: The City that Writes

- Victoria Harms: Rebels, Revolutions, and the Right-Wing Backlash

De Guzman continued with a question-answer session with panelists, including questions and discussion with audience members.

Q: Describe integrating CBL into your course, and what motivated you?

VH: I heard a talk by Dr. Shawntay Stocks on CBL in 2018. I was relatively new and did not feel very comfortable on the Homewood campus at that time. But my students began asking me more and more questions about Baltimore. CBL offered an opportunity to bring Baltimore into my course from different viewpoints.

MP: I started thinking about how to connect goals in our classroom with the community. Grade school kids, including high schoolers, take courses in storytelling. The partners for us have been students in their late teens and early twenties from all across Baltimore City. CBL allows me to bring peers to my students from the community.

JBJ: Prior to my current position, I ran a nonprofit in West Africa for twelve years and recognize that the stories, knowledge, and ancestral wisdom of people of color across the globe is intentionally left out of Western academic practices. If we’re going to really think about the cultivation of knowledge, we have to engage with our communities, with people who are doing the work, who are finding solutions. That is my commitment. This is where it starts if we’re going to be better humans, researchers, and scholars.

AEB: I really like the way CBL expands students’ sense of what an education is and also what is considered expertise. Educators are not just those with a particular degree, but include others who are outside of the classroom: administrators, performers, musicians, etc. CBL also helps students expand their sense of what it means to be in college and not be defined by their major or a particular class. It helps them understand what they could learn in the moment, instead of five years from now. It also gives students an interdisciplinary experience and encourages them to question the idea of disciplinary boundaries.

ABM: I teach a year-long multidisciplinary design course where students work with an external project partner for two semesters. Students like working on social impact projects, being part of something bigger than themselves. I was hesitant at first to bring these types of projects to students without the proper resources; I had some experience working overseas and recognized the challenges of projects like these. The Faculty Fellows program has great structure. It takes massive amounts of time, almost like having a part-time job, but it’s been a great platform to work with Baltimore City Rec and Parks.

Q: How did you manage the logistical side of starting up the partnerships and managing the relationships with the organization you worked with?

MP: It was a rough introduction with Wide Angle Youth Media at first. I came in with a pedagogical model that I had used previously, where students produce work for the organization. The organization’s response was slightly cold – they weren’t sure about our involvement. I stepped back and adjusted assignments and reconfigured the syllabus. We kept communicating which built up trust and things gradually improved. This is all part of the inherent messiness and flexibility that we as teachers have to be ready for.

AEB: I was brand new to OrchKids. My kids play music, so I was familiar with the program, but I was new to them. Once they (OrchKids) got the ‘okay’ to go through with it, we set up weekly Zoom meetings. The logistics were taken care of by Luisa De Guzman.

VH: Finding partners is a challenge and may be a deterrent. You have to acknowledge the legitimate reservations that people have about working with Hopkins. Positionality and cultural humility are lessons that I took away for myself. As a white woman from Hopkins I would show up in certain spaces in Baltimore and not always be welcome. After months of going to events and talking to people, I was able to make a connection at the Reginald F. Lewis Museum. Like Matt said, you keep building on the relationships.

Q: Do these organizations approach the Center for Social Concern (CSC)? Or is it an organic process?

Q: Do these organizations approach the Center for Social Concern (CSC)? Or is it an organic process?

JBJ: It’s generally an organic process. Luisa is very diligent about not matching people with organizations, or vice versa, but with establishing connections and helping people find their way together. We have a lot of community partners that span our different programs. And we’re looking at ways to continue to encourage more. We’re doing this through community happy hours with our partners and bringing people together just to get to know each other, to see what sparks and what ideas can come into fruition.

ABM: I had a booklet of past projects that I looked through and sought out partners that might have something to do with engineering. I reached out and asked if anyone had contacts, made a few calls, and figured out a project from there.

MP: One thing I found a little surprising – my students got a sense of higher stakes in the class. With the addition of the community partners, it’s like the tent got bigger. The stakes got a little higher, while still being relatively safe enough for novice writers. They realized, “We’re doing something cool. It matters to people more than just us.”

Q: How do you assess student learning in the CBL course?

AEB: The work that was going to get evaluated was the work of writing. I asked the folks at OrchKids if there was something our students could do for them in terms of writing or researching, but there was not.

MP: The answer to the question, which is a great question, depends on the pedagogical context of the content. CBL is essentially introducing students to a context for writing and a community for doing that.

VH: In my class, an upper-level writing intensive History class, there are reading assignments about Baltimore’s history in the 1960s. There are also two research papers, one of which is on Baltimore. At the end of the semester, I asked students, “What do we do about the participation grade?” I asked them to decide how they wanted to be assessed on participation and I walked out of the room. When I walked back in, they had a whole argument laid out about why they each deserved 100%. But it was a meaningful argument, so I was fine with it.

JBJ: It’s a real struggle in my course because I have students from many disciplines (public health, anthropology, theatre, etc.). There are public health outcomes that are central points to the course, but also historical content they are exposed to during the engagement with the community. It becomes an evaluation of the discussions that take place in the community, about the readings, and reflecting with each other.

Q: Is anyone documenting this pedagogy?

MP: UWP is constructing a digital resource for teaching and writing: “The Teaching and Writing Toolkit.” It will contain some subsections about CBL, including community engaged syllabi, writing assignments, and rubrics that folks would need to evaluate this work.

JBJ: We’d like to move towards doing research about our practice and write about it. That’s a direction that we are excitedly heading in.

VH: We are a data-driven institution. I added extra questions on the course evaluations and published an article. You do it through publications.

Q: One of the challenges of incorporating CBL is the budget and how it goes into the community. And what happens once the funding ends?

JBJ: As a Faculty Fellow you receive $5000 to work with – this can cover a range of things like materials to student transportation. In my case, the money went to transporting my students and the rest of the balance went to my community partner, the Blacks in Wax Museum. In terms of what happens after we’re done, Anand Pandian in Anthropology found a way for his community co-instructor to become a lecturer at Hopkins. It’s on us as faculty to really advocate for these opportunities. We also need to have more ways to build in how we apply for [CBL] grants together. I am hopeful there will be more happening in the way of tenure and promotion that allows faculty to count engaged scholarship and public facing scholarship.

Q: If students are already involved with an organization, is there a way for them to be recognized (with credit or other) for their efforts so that it also becomes a student-driven initiative?

Q: If students are already involved with an organization, is there a way for them to be recognized (with credit or other) for their efforts so that it also becomes a student-driven initiative?

JBJ: I’ve had students do independent studies with me for credit. These students often remain engaged in the work beyond the initial encounter and sometimes end up working as interns at the CSC.

MP: One of the recommendations from CUE2 is about bringing students’ curriculum, co-curricular, and extra-curricular experiences closer together. We need to stand up credit bearing experiences for students that are not just issued from academic offices, but from experiential learning experiences. This is happening across the country. We could position ourselves as leaders in this area.

Q: I feel like the K-12 environment has been doing this work for a long time. How much do you feel like you’re learning from the K-12 space?

MP: It might be telling about the insularity of Higher Ed that I’m thinking to myself, I’m not really familiar with the conversations happening in Primary and Secondary Ed around those ways.

JBJ: The School of Education is taking innovative steps with how they assess their grad students. They are accepting portfolios rather than just a straightforward dissertation. I think there’s movement there, more so with the profession than with the disciplines, which isn’t surprising. In the professions, in nursing and medicine, narrative medicine has been a thing for a very long time. Now there are reports from national academies about how we use a variety of forms of knowledge creation beyond solely the written text. It comes down to how you evaluate it, not just the long-written paper.

Q: Please tell us a word that summarizes your community-based learning experiences thus far.

VH: Cultural humility.

MP: Potential. We got started, something happened. But the future version of it is the most exciting version, I think.

JBJ: Reparative, and beyond just the relational physical repair.

AEB: Plaid. Some of it was a mess, some of it was personal, and it was all very political. So when you put that together, you get “plaid.”

ABH: Hopeful. There are positive responses from the students, and I think that good things are going to come from what they’re producing.

References:

Kuh, George D. (2008). “High-impact educational practices: What they are, who has access to them, and why they matter.” AAC&U, Washington, D.C. 34 pp.

Amy Brusini, Senior Instructional Designer

Center for Teaching Excellence and Innovation

Image Sources: Lunch and Learn Logo, Pixabay