[Guest post by Molly Warnock, Assistant Professor, History of Art, Johns Hopkins University]

The library is often called the lab of the humanities. In my experience, the Johns Hopkins Sheridan Libraries embraces this role. I collaborate regularly with the Libraries’ staff to encourage students not only to use library resources to conduct their research but also to use the physical space to present their findings. In several of my undergraduate art history courses, students curate an exhibition as one of their major assignments. This article provides an overview of my collaboration with the Sheridan Libraries and describes a model that my colleagues are considering adopting for their own course projects.

The collaboration began when I discovered the extensive modern and avant-garde collections owned by the Libraries, which boast vast reserves of journals, rare exhibition catalogues, and artists’ books, as well as posters, pamphlets, and other ephemera. I  wanted to integrate these materials into my courses, and started by setting aside a day or two every semester to visit Special Collections. Now virtually all of my courses at all levels include multiple sessions of this sort. For example, my introductory survey “Modern Art, 1880-1950,” includes thematic visits devoted to such topics as Futurist typography, the role of journals and little magazines in the spread of experimental practices, and utopian urbanism. These visits allow students to see and in many cases handle rare primary materials, adding substantively to our discussions in the classroom. They are almost always surprised to discover the extent of our collections.

wanted to integrate these materials into my courses, and started by setting aside a day or two every semester to visit Special Collections. Now virtually all of my courses at all levels include multiple sessions of this sort. For example, my introductory survey “Modern Art, 1880-1950,” includes thematic visits devoted to such topics as Futurist typography, the role of journals and little magazines in the spread of experimental practices, and utopian urbanism. These visits allow students to see and in many cases handle rare primary materials, adding substantively to our discussions in the classroom. They are almost always surprised to discover the extent of our collections.

The curatorial seminars that I have developed over the past six years are specifically aimed at increasing student engagement with these important library holdings. Each course is in certain respects a traditional seminar, focused on some area of twentieth-century practice. We have weekly readings, look at digital slideshows, and discuss various case studies. At the same time, however, students immerse themselves in a semester-long, hands-on curatorial project centered on one particular aspect of our subject matter. The first such course, “Surrealism,” produced a survey of Surrealist journals (“Surrealism at Mid-Century”), while the second, “The ‘Long Sixties’ in Europe,” turned the spotlight on the library’s wealth of Lettrist books, journals, posters, photographs, and film scripts, among other items (“Presenting: Lettrism”). Additional iterations of “The ‘Long Sixties’” have focused on the library’s recently expanded trove of materials relating to the avant-garde group Cobra (“Asger Jorn and Cobra”) and on the Paris-based journal Robho (“Robho in Context”). Student contributions drive all stages of the project, including: researching and studying the available holdings; crafting a final object list; writing exhibition labels for the selected works; and designing the exhibition layout. At the exhibition opening, the students serve as docents, guiding interested members of the Hopkins community through the show.

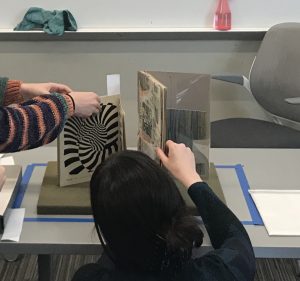

Collectively curating an exhibition in one semester means negotiating difficult time constraints. I start my course planning by identifying a long list of objects relevant to my course. Throughout this period, I consult extensively with Don Juedes, the dedicated librarian for History of Art. We then meet with Mark Pollei and Alessandro Scola of the Conservation and Preservation team to ensure that the pre-selected objects are stable enough to be handled repeatedly and determine vulnerabilities that would have to be taken into consideration for exhibition—whether, for instance, a particular book or journal is especially light sensitive, or can only be opened halfway. Once the semester is underway, students begin working on the exhibition immediately. Within the first week, we’re in Special Collections, where students get their first peek of the objects cleared for exhibition; each selects a few to research individually. I provide some initial context, but encourage them to choose based on their broader interests or curiosity about specific items.

Collectively curating an exhibition in one semester means negotiating difficult time constraints. I start my course planning by identifying a long list of objects relevant to my course. Throughout this period, I consult extensively with Don Juedes, the dedicated librarian for History of Art. We then meet with Mark Pollei and Alessandro Scola of the Conservation and Preservation team to ensure that the pre-selected objects are stable enough to be handled repeatedly and determine vulnerabilities that would have to be taken into consideration for exhibition—whether, for instance, a particular book or journal is especially light sensitive, or can only be opened halfway. Once the semester is underway, students begin working on the exhibition immediately. Within the first week, we’re in Special Collections, where students get their first peek of the objects cleared for exhibition; each selects a few to research individually. I provide some initial context, but encourage them to choose based on their broader interests or curiosity about specific items.

One of the course goals is to teach students how to interpret primary materials using different research strategies. Their first assignment is to outline a research plan for each of their chosen objects. Don introduces the students to library resources and teaches them the skills needed to conduct their research: for example, how to meaningfully generate and delimit searches in our online catalogue and how to navigate various databases and bibliographies. They have to locate relevant materials using the strategies Don has shared with them, and indicate how they plan to build an argument from these sources. This can be quite challenging in the case of objects that have not been studied extensively by scholars to date. I provide feedback and encourage them to think broadly about different angles of attack, from the more obvious (researching the artist or author) to the less immediately apparent (researching a gallery’s broader exhibition agenda).

By mid-semester, we are all back in Special Collections, where the students present their objects and recommend specific display options, based on their research findings and the various larger stories we might wish to tell. We then move into the most exciting—and difficult—phase: experimenting with different installation plans and whittling down our final object selection. We mark off spaces equivalent to the various display cases and physically move things around until we feel we’ve arrived at a coherent, visually compelling narrative. The Conservation and Preservation team stop by again to consult with us about our display concept, and then spend roughly a month and a half preparing the featured materials, building customized cradles, and installing the objects. The students use that same period to produce and collectively edit the banner text and individual object labels. The official opening usually takes place in the penultimate week of the semester and serves as a celebratory capstone for the course as a whole.

The Conservation and Preservation team stop by again to consult with us about our display concept, and then spend roughly a month and a half preparing the featured materials, building customized cradles, and installing the objects. The students use that same period to produce and collectively edit the banner text and individual object labels. The official opening usually takes place in the penultimate week of the semester and serves as a celebratory capstone for the course as a whole.

As an instructor, it is deeply satisfying to see how seriously the students take one another’s research, and how effectively a collaborative project of this sort can help to build community. I find myself continually refining my pedagogical approach to facilitate this. One crucial step was simply to limit the class size to a maximum of ten students. I’ve also explored the potential of new technological platforms to facilitate more lateral processes of peer-to-peer discussion and group editing. For example, having students generate and refine all exhibition-related texts in Google Docs allows me to afford class participants greater responsibility for the finished products, while still tracking individual contributions. This can be awkward at first, as students may not have prior experience giving one another constructive criticism. But they quickly learn that robust peer critique results in a better overall outcome: an exhibition that represents all of their contributions.

In their course evaluations, students rate this experience highly positively. One described “the opportunity to curate an exhibition and work with objects from the library’s collections” as “truly special,” while another called it “unlike anything I had done for a course at Hopkins before,” adding: “Interacting with one another so regularly to work on the exhibition also built a great sense of community among the students.” A third noted: “I really enjoyed getting to spend so much time physically with all these artifacts, and doing research on objects JHU owned.”

This project has also deepened my working relationship with Don Juedes. Don’s assistance has been instrumental at every stage. Early on, he helped me to put together an exhibition proposal and worked with the exhibition committee to significantly expedite the review process, which had previously taken several months. (Based on the success of previous course- related curatorial project, the Libraries now dedicate a regular slot in the calendar to our exhibitions.) He has also worked closely with library staff from multiple departments to streamline workflows and pin down a project timeline.

At the same time, Don and I consult regularly about the collections and often tailor new acquisitions in my research area to the courses I plan to teach and the kind of student-curated exhibitions that might accompany them. For the students, there is an added benefit: working closely with Don teaches them the multi-faceted role that libraries play in supporting the scholarly community. They see that libraries are not just passive repositories but have a highly active custodial and, indeed, curatorial role, assembling and caring for the materials that enable forward-looking research and teaching. They learn the importance of developing relationships with library staff that can provide complementary expertise and assist in the discovery process. The students in these curatorial seminars often become avid library patrons, returning to use primary sources for other courses and independent research projects.

For the students, there is an added benefit: working closely with Don teaches them the multi-faceted role that libraries play in supporting the scholarly community. They see that libraries are not just passive repositories but have a highly active custodial and, indeed, curatorial role, assembling and caring for the materials that enable forward-looking research and teaching. They learn the importance of developing relationships with library staff that can provide complementary expertise and assist in the discovery process. The students in these curatorial seminars often become avid library patrons, returning to use primary sources for other courses and independent research projects.

My partnership with the library has changed how I teach and opened up new learning experiences for students. I feel incredibly fortunate that the Libraries’ leadership and outstanding staff at all levels fully grasp the importance of teaching with objects and so generously support pedagogical innovation and collaboration in this area.

Molly Warnock, Assistant Professor

History of Art, Johns Hopkins University

In addition to critical surveys of modern and contemporary art, Molly Warnock’s recent and forthcoming undergraduate courses include several seminars with curatorial components, each focused on particular aspects of twentieth-century practice and culminating in an exhibition of journals and other ephemera from the Special Collections of the Sheridan Libraries. Recent graduate courses have explored the philosophical underpinnings of art history as a modern discipline; problems in abstraction; theories of painting and subjectivity; and the concept of an aesthetic medium, among other topics.

Image Source: Don Juedes