This post was submitted by Atousa Saberi, a graduate student in the Johns Hopkins Teaching Academy who reflected on her first-time teaching experience.

I would like to share my learning experience as a PhD student teaching my first undergraduate course during fall 2020: Natural Hazards.

Teaching this course, I wrestled with several questions: How can I engage students in a virtual setting? How can I make them think? What is the purpose of education after all and what do I want them to take away from the course?

About the course setting

Fall semester 2020 was a unique time to teach a course on natural hazards in the sense that all students were directly impacted by at least one type of disaster – the global pandemic. In addition, the semester coincided with a record-breaking Atlantic hurricane season on the East Coast and fires on the West Coast. I used these events as an opportunity to spark students’ curiosity and motivate them to learn about the science of natural hazards.

As a student, my best learning experiences happened through dialogues and exchange of ideas between classmates and instructors that continued back and forth during class time. This experience inspired me to hold more than half of the class sessions synchronously.

To focus students’ attention, I motivated every class session by posing questions. For example, which hazards are the most destructive, frequent, or deadly? What is the effect of climate change on these hazards? What can we do about them? Some of these questions are open ended and may sound overwhelming at first, but to me, the essential step in learning is to become curious enough to engage with questions and take steps to answer them. Isn’t the purpose of education to train future thinkers?

The course included clear learning objectives following Bloom’s Taxonomy to target both lower- and higher-level thinking skills. I designed multiple forms of assignments such as conducting readings, listening to podcasts, watching documentaries, completing analytical exercises, and participating in group discussions. To motivate the sense of exploration in students, instead of exams, I assigned a final term paper in which students investigated a natural disaster case study of their own interest.

The assessment was structured using specifications grading. The method directly links course grades to achievements of learning objectives and motivates students to focus on learning instead of earning points (Kelly, 2018). Grading rubrics were provided for each individual assignment.

Lab demonstrations

Just as a picture is worth a thousand words, lab demonstrations go a long way to supplement lectures and to improve conceptual understanding of learning materials. But is it possible to perform them in a remote setting?

Simple demonstrations were still possible. I just needed to get creative in implementing them! For example, I used a rubber band and a biscuit to demonstrate the strength of brittle versus elastic materials under various modes of deformation to explain how the choice of materials can make a drastic difference in what modes of deformation a building tolerates during an earthquake, which impacts the survival rate during an earthquake.

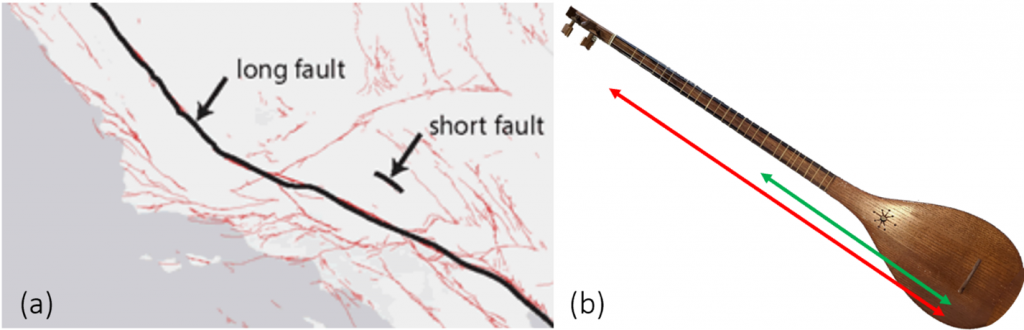

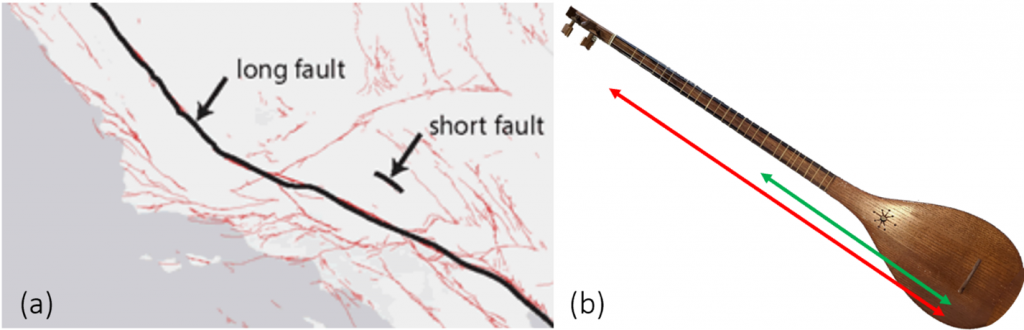

I also used a musical instrument, my Setar, as an analogy for seismic waves. Just seeing the instrument immediately captured the students’ attention. I played the same note at different octaves and reminded them how that results in a different pitch due to the string being confined to two different lengths. This is analogous to having a short versus long earthquake fault and therefore higher or lower frequency in seismic waves (Figure 1). Students were also given an exercise to listen to the sound of earthquakes from an archive to infer the fault length.

Figure 1. Comparison of seismic waves to the sound waves generated by a string instrument. (a) length of two Earthquake faults (USGS). (b) music instrument producing analogous sound waves. The red and green arrows show the note, D, played on the same string in different octaves.

Figure 1. Comparison of seismic waves to the sound waves generated by a string instrument. (a) length of two Earthquake faults (USGS). (b) music instrument producing analogous sound waves. The red and green arrows show the note, D, played on the same string in different octaves.

Freedom to learn

Noam Chomsky often says in his interviews about education that students are taught to be passive and obedient rather than independent and creative (Robichaud, 2014). He believes education is a matter of laying out a string along which students will develop, but in their own way (Chomsky & Barsamian, 1996). Chomsky quotes his colleague’s response to students asking about course content, saying “it is not important what we cover in the class but rather what we discover” (Chomsky & Barsamian, 1996). I was inspired by this perspective and decided to encourage the enlightenment style of learning in my students by giving them freedom in their final term paper writing style. I encouraged the students to pick a case study based on what they loved to learn about natural hazards and gave them freedom in how to structure their writing or what to expand on (the science of the disaster, the losses, the social impacts, the aftermath, etc.). I was surprised to see so many of the students asked for strict guidelines, templates and sample term papers from previous semesters, as if the meaning of freedom and creativity in learning was unfamiliar to them!

Student perceptions of the class

I administered two anonymous feedback surveys, one in the middle of the semester and the other at the end. The mid-semester survey was focused on understanding what is working (not working) for students that I should keep (stop) doing, and what additional activities we could start doing to better adapt to the unexpected transition to online learning. I learned that students had a lot to say, some of which I incorporated in the second half of the semester, such as taking a class session to practice writing the term paper and hold a Q&A session.

The end-of-semester survey was more focused on their takeaways from the class, and what assignments/activities were most helpful in their learning experience. I specifically asked them questions such as, “What do you think you will remember from this course? What did you discover?”

The final survey revealed that by the end of the semester students, regardless of their background, comprehended the major earth processes and reflected on the relation between humans and natural disasters. They grasped the interdisciplinary nature of the course and how one can learn about intersection of physics, humanities, and international relations through studying natural hazards and disasters. They also developed a sense of appreciation for the role of science in predicting and dealing with natural hazards.

What I learned

Even though universities like Hopkins often train Ph.D. students to focus on producing publications rather than doing curiosity-driven research, I found that teaching a course like this led me to ask the kind of fundamental questions that could stimulate future research. This experience helped me develop as a teacher, as well as a true scientist, while raising awareness and sharing important knowledge about natural hazards in a changing climate in which the frequency of hazardous events will likely increase. I captured students’ attention by making the learning relevant to their lives, which inspired their curiosity. Feedback surveys revealed and reinforced my idea that synchronous class discussions, constant questioning, and interesting lab demos would hook the students and motivate them to engage in dialogue.

I am grateful to the KSAS Dean’s Office for making teaching as a graduate student possible, to the Center for Educational Resources for providing great teaching resources, and to Dr. Rebecca Kelly for her continuous support and valuable insights during the period I was teaching, to Dr. Sabine Stanley and Thomas Haine for their encouragement and feedback on this essay.

Atousa Saberi

References:

Kelly, R. (2018). Meaningful grades with specification grading. https://cer.jhu.edu/files/InnovInstruct-Ped-18 specifications-grading.pdf

Robichaud, A. (2014). Interview with Noam Chomsky on education. Radical Pedagogy, 11 (1), 4.

Chomsky, N., & Barsamian, D. (1996). Class warfare: interviews with David Barsamian. Monroe, Maine: Common Courage Press. 5

USGS (2020), Listening to earthquake: https://earthquake.usgs.gov/education/listen/index.php.

Image Source: Pixabay, Atousa Saberi

effort and growth. Think of it like going to the gym. At first, lifting weights might feel impossible, but over time, you get stronger. Learning works the same way.”

effort and growth. Think of it like going to the gym. At first, lifting weights might feel impossible, but over time, you get stronger. Learning works the same way.”