Dr. Culhane is Professor and Chair of the Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences at Notre Dame of Maryland University School of Pharmacy.

If you are like me, much of your time is spent ensuring that the classroom learning experience you provide for your students is stimulating, interactive and impactful. But how invested are we in ensuring that what students do outside of class is productive? Based on my anecdotal experience and several studies1,2,3 looking at study strategies employed by students, the answer to this question is not nearly enough! Much like professional athletes or musicians, our students are asked to perform at a high level, mastering advanced, information dense subjects; yet unlike these specialists who have spent years honing the skills of their craft, very few students have had any formal training in the basic skills necessary to learn successfully. It should be no surprise to us that when left to their own devices, our students tend to mismanage their time, fall victim to distractions and gravitate towards low impact or inefficient learning strategies. Even if students are familiar with high impact strategies and how to use them, it is easy for them to default back to bad habits, especially when they are overloaded with work and pressed for time.

Several years ago, I began to seriously think about and research this issue in hopes of developing an evidence-based process that would be easy for students to learn and implement. Out of this work I developed a strategy focused on the development of metacognition – thinking about how one learns. I based it on extensively studied, high impact learning techniques to include: distributed learning, self-testing, interleaving and application practice.4 I call this strategy the S.A.L.A.M.I. method. This method is named after a metaphor used by one of my graduate school professors. He argued that learning is like eating a salami. If you eat the salami one slice at a time, rather than trying to eat the whole salami in one setting, the salami is more likely to stay with you. Many readers will see that this analogy represents the effectiveness of distributed learning over the “binge and purge” method which many of our students gravitate towards.

S.A.L.A.M.I. is a “backronym” for Systematic Approach to Learning And Metacognitive Improvement. The method is structured around typical, daily learning experiences that I refer to as the five S.A.L.A.M.I. steps:

- Pre-class preparation

- In-class engagement

- Post-class review

- Pre-exam preparation

- Post-assessment review

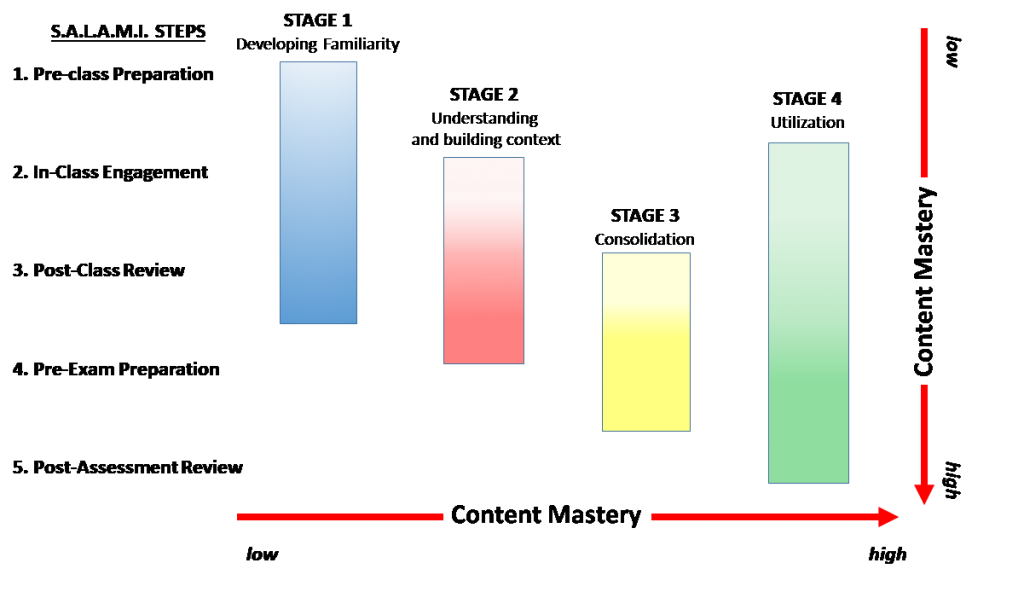

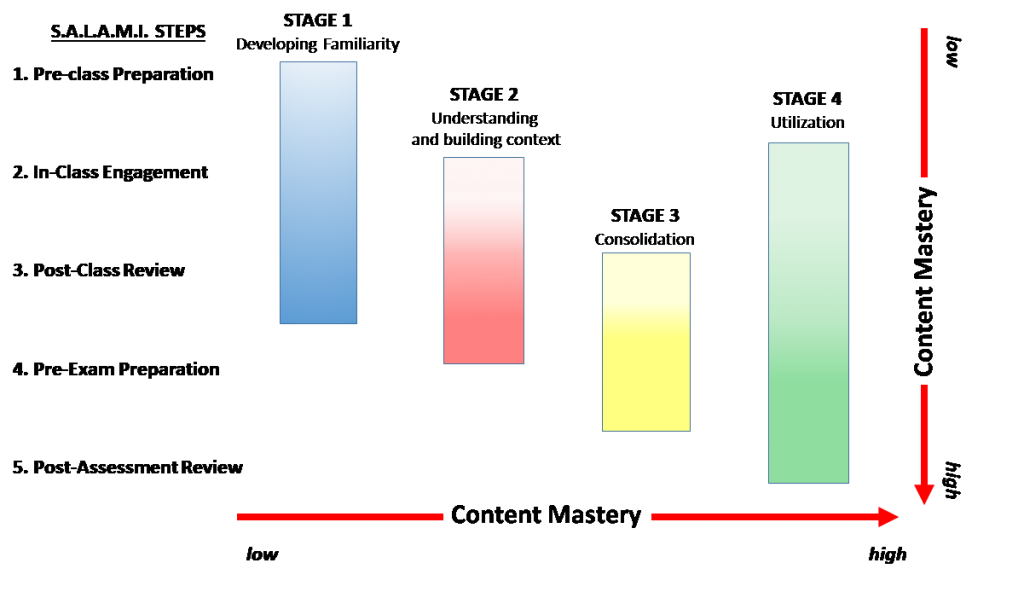

When teaching the S.A.L.A.M.I. method, I explain how each of the five steps correspond to different “stages” or components of learning (see figure 1). Through mastery of skills associated with each of the five S.A.L.A.M.I. steps, students can more efficiently and effectively master a subject area.

Figure 1

Despite its simplicity, this model provides a starting point to help students understand that learning is a process that takes time, requires the use of different learning strategies and can benefit from the development of metacognitive awareness. Specific techniques designed to enhance metacognition and learning are employed during each of the five steps, helping students use their time effectively, maximize learning and achieve subject mastery. Describing all the tools and techniques recommended for each of the five steps would be beyond the scope of this post, but I would like to share two that I have found useful for students to evaluate the effectiveness of their learning and make data driven changes to their study strategies.

Let us return to our example of professional athletes and musicians: these individuals maintain high levels of performance by consistently monitoring and evaluating the efficacy of their practice as well as reviewing their performance after games or concerts. If we translate this example to an academic environment, the practice or rehearsal becomes student learning (in and out of class) and the game or concert acts as the assessment. We often evaluate students’ formative or summative “performances” with grades, written or verbal feedback. But what type of feedback do we give them to help improve the efficacy of their preparation for those “performances?” If we do give them feedback about how to improve their learning process, is it evidenced-based and directed at improving metacognition, or do we simply tell them they need to study harder or join a study group in order to improve their learning? I would contend that we could do more to help students evaluate their approach to learning outside of class and examination performance. This is where a pre-exam checklist and exam wrapper can be helpful.

The inspiration for the pre-exam checklist came from the pre-flight checklist a pilot friend of mine uses to ensure that he and his private aircraft are ready for flight. I decided to develop a similar tool for my students that would allow them to monitor and evaluate the effectiveness of their preparation for upcoming assessments. The form is based on a series of reflective questions that help students think about the effectiveness of their daily study habits. If used consistently over time and evaluated by a knowledgeable faculty or learning specialist, this tool can help students be more successful in making sustainable, data driven changes in their approach to learning.

Another tool that I use is called an exam wrapper. There are many examples of exam wrappers online, however, I developed my own wrapper based on the different stages or components of learning shown in figure 1. The S.A.L.A.M.I. wrapper is divided into five different sections. Three of the five sections focus on the following stages or components of learning: understanding and building context, consolidation, and application. The remaining two sections focus on exam skills and environmental factors that may impact performance. Under each of the five sections is a series of statements that describe possible reasons for missing an exam question. The student analyzes each missed question and matches one or more of the statements on the wrapper to each one. Based on the results of the analysis, the student can identify the component of learning, exam skill or environmental factors that they are struggling with and begin to take corrective action. Both the pre-exam checklist and exam wrapper can be used to help “diagnose” the learning issue that academically struggling students may be experiencing.

Two of the most common issues that I diagnose involve illusions of learning5. Students who suffer from the ‘illusion of knowledge’ often mistake their understanding of a topic for mastery. These students anticipate getting a high grade on an assessment but end up frustrated and confused when receiving a much lower grade than expected. Information from the S.A.L.A.M.I. wrapper can help them realize that although they may have understood the concept being taught, they could not effectively recall important facts and apply them. Students who suffer from the ‘illusion of productivity’ often spend extensive time preparing for an exam, however, the techniques they use are extremely passive. Commonly used passive study strategies include: highlighting, recopying and re-reading notes, or listening to audio/video recordings of lectures in their entirety. The pre-exam checklist can help students identify the learning strategies they are using and reflect on their effectiveness. When I encounter students favoring the use of passive learning strategies I use the analogy of trying to dig a six-foot deep hole with a spoon: “You will certainly work hard for hours moving dirt with a spoon, but you would be a lot more productive if you learned how to use a shovel.” The shovel in this case represents adopting strategies such as distributed practice, self-testing, interleaving and application practice.

Rather than relying on anecdotal advice from classmates or old habits that are no longer working, students should seek help early, consistently practice effective and efficient study strategies, and remember that digesting information (e.g. a S.A.L.A.M.I.) in small doses is always more effective at ‘keeping the information down’ so it may be applied and utilized successfully later.

- Kornell, N., Bjork, R. The promise and perils of self-regulated study. Psychon Bull Rev. 2007;14 (2): 219-224.

- Karpicke, J. D., Butler, A. C., & Roediger, H. L. Metacognitive strategies in student learning: Do students practice retrieval when they study on their own? Memory. 2009; 17: 471– 479.

- Persky, A.M., Hudson, S. L. A snapshot of student study strategies across a professional pharmacy curriculum: Are students using evidence-based practice? Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2016; 8: 141-147.

- Dunlosky, J., Rawson, K.A., Marsh, E.J., Nathan, M.J., Willingham, D.T. Improving Students’ Learning With Effective Learning Techniques: Promising Directions From Cognitive and Educational Psychology. Psychol Sci Publ Int. 2013; 14 (1): 4-58.

- Koriat, A., & Bjork, R. A. Illusions of competence during study can be remedied by manipulations that enhance learners’ sensitivity to retrieval conditions at test. Memory & Cognition. 2006; 34: 959-972.

James M. Culhane, Ph.D.

Chair and Professor, School of Pharmacy, Notre Dame of Maryland University

Each spring, I teach a course called Culture of the Engineering Profession for the Center for Leadership Education in the Whiting School. Primarily through discussions and projects, students in this class investigate what it means to be an engineer, identify contemporary issues in engineering, and consider the ethical guidelines of the engineering profession. The majority of students in the Spring 2019 class were Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering majors with a Mechanical Engineering student mixed in. This semester, I decided to experiment somewhat with guided reflection, a metacognitive practice that was new for many of these students.

Each spring, I teach a course called Culture of the Engineering Profession for the Center for Leadership Education in the Whiting School. Primarily through discussions and projects, students in this class investigate what it means to be an engineer, identify contemporary issues in engineering, and consider the ethical guidelines of the engineering profession. The majority of students in the Spring 2019 class were Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering majors with a Mechanical Engineering student mixed in. This semester, I decided to experiment somewhat with guided reflection, a metacognitive practice that was new for many of these students.