We’re always on the lookout for applications that instructors and their students can use to enhance course work. A previous post We Have a Solution for That: Student Presentations, Posters, and Websites (October 6, 2017) mentioned a new version of Google Sites as having potential as a presentation software that allows for easy collaboration among student team members. Today’s post will delve deeper into its possibilities and use. This post is also available in PDF format as part of The Innovative Instructor articles series.

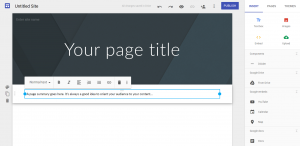

New Google Sites is an online website creation platform. It doesn’t require web development or design experience to create sites that work well on mobile devices. The New Google Sites application is included with the creation tools offered in Google Drive, making it easier to share and integrate your Google Drive content.

New Google Sites is an online website creation platform. It doesn’t require web development or design experience to create sites that work well on mobile devices. The New Google Sites application is included with the creation tools offered in Google Drive, making it easier to share and integrate your Google Drive content.

In 2006 Google purchased JotSpot, a software company that had been creating social software for businesses. The software acquired from that purchase was used to create the first iteration of Google Sites, now known as Classic Google Sites. Ten years later, Google launched a completely rebuilt Google Sites, which is currently being referred to as New Google Sites.

New Google Sites hasn’t replaced Classic Google Sites so much as it offers a new and different experience. The focus of New Google Sites is to increase collaboration for all team members regardless of their web development experience. It is also integrated with Google Drive so that teams working within the Google apps environment can easily associate shared content.

This new iteration of Google Sites is designed with mobile devices in mind. Users are

not able to add special APIs (Application Programmable Interface, which extends functionality of an application) or edit HTML directly. This keeps the editing interface

and options simple to ensure that whatever you create will work consistently across all browsers and devices. While this may seem limiting, you still have the option to use Classic Google Sites if you want a higher level of control.

In a classroom setting, instructors are often cautious about assigning students projects that require them to learn new technical skills that aren’t directly relevant to the course content. Instructors must balance the time it will take students to achieve technical competency against the need to ensure that students achieve the course learning goals. With New Google Sites, students can focus on their content without being overwhelmed by the technology.

In addition to ease of use, collaborative features allow students to work in teams and share content. Group assignments can offer students a valuable learning experience by providing opportunities for inclusivity, exposure to diverse viewpoints, accountability through team roles, and improved project outcomes.

New Google Sites makes it easy for the causal user to disseminate new ideas, original research, and self-expression to a public audience. If the website isn’t ready to be open to the world, the site’s editor has the ability to keep it unpublished while still having the option to collaborate or share it with select people. This is an important feature as student work may not be ready for a public audience or there may be intellectual property rights issues that preclude public display.

Professors at here at Johns Hopkins have used New Google Sites for assignments. In the History of Science and Technology course, Man vs. Machine: Resistance to New Technology since the Industrial Revolution, Assistant Professor Joris Mercelis had students use New Google Sites for their final projects. Teams of two or three students were each asked to create a website to display an illustrated essay based on research they had conducted. Images and video were required to support their narrative arguments. Students had to provide proper citations for all materials. Mercelis wanted the students to focus on writing for a lay audience, an exercise that encouraged them to think broadly about the topics they were studying.

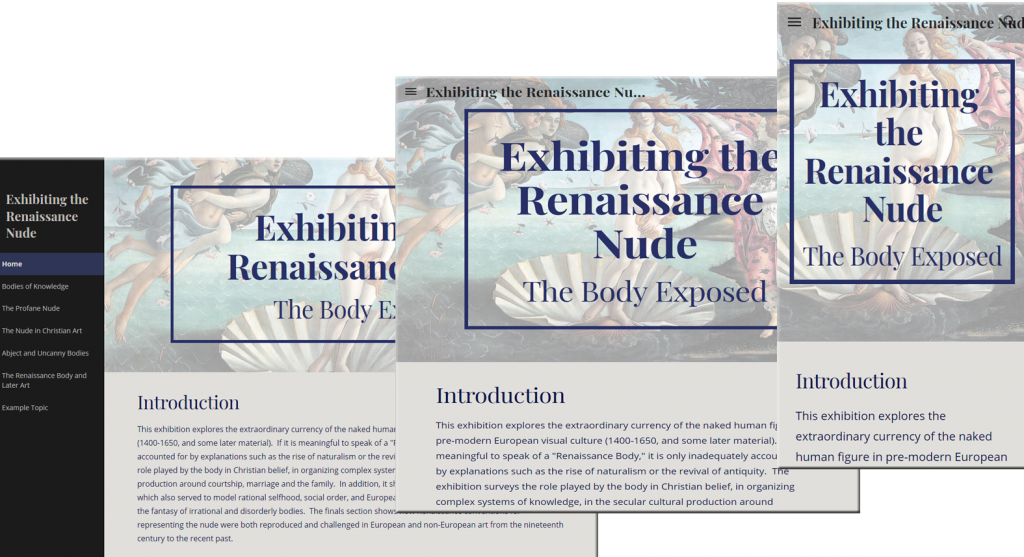

History of Art Professor Stephen Campbell used a single Google Site where student teams collaborated to produce an online exhibition, Exhibiting the Renaissance Nude: The Body Exposed. Each student group was responsible for supplying the materials for one of five topic pages. The content developed from this project was accessible only to the class.

In both cases, students reported needing very little assistance when editing their sites. Typically, giving an introductory demonstration and providing resources for where to find help are all students need to begin working.

Recently, Google has created the ability to allow other Google Drive content to be embedded in a site. This means that you can embed a form or a document on a web page to elicit responses/feedback from your audience without them having to leave the site. This level of integration further supports the collaborative nature of Google applications.

Currently, this iteration of Google Sites uses the New in its title. There may come a time when Google will drop the New or re-brand New Google Sites with a different name. There is no indication that Google will stop supporting Classic Google Sites with its more advanced features.

Use of both versions of Google Sites is free and accessible using your Google Account. You can create a new site by signing into Google and going to the New Google Sites page (link provided below). You can also create a site from Google Drive’s “New” button in the creation tools menu.

It is recommended that students create a new account for class work instead of using their personal accounts. While this is an additional step, it ensures that they can keep their personal lives separated from their studies.

Additional Resources:

- New Google Sites: https://sites.google.com/new

- New and Classic Google Sites comparison: https://support.google.com/sites/answer/7176163

Reid Sczerba, Multimedia Developer

Center for Educational Resources

Image sources: Google Sites logo, screenshots