Student engagement is a critical component of higher education and a frequent topic of interest among instructors. Actively engaging students in the learning process helps increase motivation, supports collaboration, and deepens understanding of course material. Finding activities that instructors can implement quickly while also proving worthwhile to students can be a challenge. I recently attended a conference with a session titled, “Low to No Prep Classroom Activities.” Jennifer Merrill, psychology professor from San Mateo County Community College, shared some simple classroom activities that require very little or no preparation ahead of time that I thought were worth sharing:

Music:

Playing music as students enter the classroom creates a shared experience which can encourage social interaction, inspire creative thinking, and lead to positive classroom dynamics. It can be used as an icebreaker, to set a particular mood, or specifically relate to the course in some way. Research shows that music stimulates activity in the brain that is tied to improved focus, attention, and memory.

- Incorporate music as part of a regular classroom routine to indicate that it’s time to focus on the upcoming lesson.

- Use it to introduce a new topic or review a current or past topic. Ask students to articulate how they think the music/artist/song relates to the course material and then share with the class.

- Allow students to suggest/select what type of music they would like to hear.

Academic Speed Dating:

Like traditional speed dating, academic speed dating consists of short, timed conversations with a series of partners around a particular topic. In this case, students are given a prompt from the instructor, briefly discuss their response with a partner, and then rotate to a new partner when the time is up. Partners face each other in two lines, with one line of students continuously shifting through the other line until they return to their original partner. This can also be done by having students form inner and outer circles, instead of lines. A few of the benefits of academic speed dating include:

In this case, students are given a prompt from the instructor, briefly discuss their response with a partner, and then rotate to a new partner when the time is up. Partners face each other in two lines, with one line of students continuously shifting through the other line until they return to their original partner. This can also be done by having students form inner and outer circles, instead of lines. A few of the benefits of academic speed dating include:

- Sharing and questioning students’ own knowledge while gaining different perspectives on a topic.

- Enhancing communication skills as students learn to express their ideas quickly and efficiently.

- Providing a safe space to share ideas as students interact with others, which can lead to a positive classroom climate.

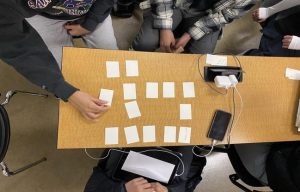

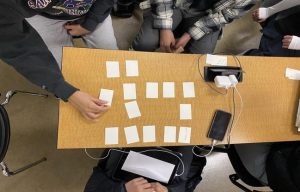

Memory:

The classic “Memory Game” consists of a set of cards with matching pairs of text or images. Cards are shuffled and placed face down; players take turns turning over 2 cards at a time, trying to find matching pairs. In this version, students take part in creating the cards themselves, using index cards, before playing the game. Memory can be used to reinforce learning and enhance the retention of course material.

Suggested steps for implementation:

1. On the board, the instructor lists 10 terms or concepts related to the course in some way.

2. Students are divided into groups of no more than 5 people. Each student in the group selects 2 terms/concepts from the list.

3. Using index cards, students write the name of the term/concept on one card, and an example of the term/concept on another card (e.g., “supply and demand” and “gasoline prices rising in the summer with more people driving”). Examples could also include images, instead of text.

4. When the groups are finished creating their sets of cards, they exchange their cards with another group and play the game, trying to match as many pairs as they can.

- Use Memory

to review definitions, formulas, or other test material in a fun, collaborative environment.

to review definitions, formulas, or other test material in a fun, collaborative environment.

- Enhance cognitive skills, such as concentration, short-term memory, and pattern recognition.

- Facilitate team building skills as students work in groups to create and play the game.

Pictionary:

In this version of classroom Pictionary, students are divided into groups that are each assigned a particular topic. Each group is tasked with drawing an image representation of their topic, e.g., “Create images that represent the function of two glial cells assigned to your group.” Ideally, it works best if drawings are large enough to be displayed  around the classroom, such as on an easel, whiteboard, or large Post-it note paper. When each group is finished with their drawings, all students participate in a gallery walk, offering feedback to the other groups. Facilitate a small or whole group discussion to reflect on the feedback each group received.

around the classroom, such as on an easel, whiteboard, or large Post-it note paper. When each group is finished with their drawings, all students participate in a gallery walk, offering feedback to the other groups. Facilitate a small or whole group discussion to reflect on the feedback each group received.

- Enhance problem solving skills and creativity by asking students to think critically about how to represent information visually.

- Use Pictionary to get students up and moving around the classroom, which will help keep them actively engaged with course content.

- Help students develop constructive feedback skills as they participate in the gallery walk part of the activity.

Hawks and Eagles:

This activity is a version of “think-pair-share” that gets students up and moving around the classroom.

Suggested steps for implementation:

1. Students pair with someone nearby and decide who will be the Hawk and who will be the Eagle.

2. Give all students a prompt or topic to discuss and allow them time to think about their response (1-3 minutes).

3. Students share their responses with their paired partner (1-3 minutes).

4. Ask Hawks to raise their hands. Ask the Eagles to get up and go find a different Hawk.

5. Students share their responses with their new partner.

6. Repeat steps 4 and 5, if desired, to allow students to pair with multiple partners.

7. Debrief topic with the whole class.

- Use Hawks and Eagles as an icebreaker activity for students to introduce and get to know one another.

- Use this activity as a formative assessment to gauge student comprehension of a particular topic.

- Expose students to multiple perspectives or viewpoints on a particular topic by having them engage with multiple partners.

IQ Cards:

IQ cards (“Insight/Question Cards”) is an exit ticket activity that acts as a formative assessment strategy. At the end of a class or unit, ask students to write down on an index card any takeaways or new information they have learned. On the other side of the card, ask them to write down any remaining questions they have about the lesson or unit. Collect student responses and share their “insights” and “questions” with the class at the next meeting.

the card, ask them to write down any remaining questions they have about the lesson or unit. Collect student responses and share their “insights” and “questions” with the class at the next meeting.

- Gather instant feedback from students and quickly assess their grasp of the material, noting where any changes or adjustments might be needed.

- Reinforce knowledge by asking students to recall key concepts of the lesson or unit.

- Use IQ Cards as a self-assessment activity for students to reflect on their own learning.

Do you have any additional low or no prep activities you use in the classroom? Please feel free to share them in the comments. If you have any questions about any of the activities described above or other questions about student engagement, please contact the CTEI – we are here to help!

Amy Brusini, Senior Instructional Designer

Center for Teaching Excellence and Innovation

References:

Baker, M. (2007). Music moves brain to pay attention, Stanford study finds. Stanford Medicine: News Center. Retrieved August 26, 2024, from https://med.stanford.edu/news/all-news/2007/07/music-moves-brain-to-pay-attention-stanford-study-finds.html

Image source: Jennifer Merrill, Pixabay

mix of students from different disciplines or majors who are not necessarily familiar with specific terms or routine practices in your specific discipline. Designing assessments that are transparent is one strategy instructors can use to address this situation.

mix of students from different disciplines or majors who are not necessarily familiar with specific terms or routine practices in your specific discipline. Designing assessments that are transparent is one strategy instructors can use to address this situation.