A few months ago, I posted about Slack, and some ideas for how it could be used in the classroom. In the article, I mentioned that JHU Professor Jennifer Bernstein regularly uses Slack to communicate with students in her classes. Since that time, we followed up with Professor Bernstein to find out more about her experience.

In the article, I mentioned that JHU Professor Jennifer Bernstein regularly uses Slack to communicate with students in her classes. Since that time, we followed up with Professor Bernstein to find out more about her experience.

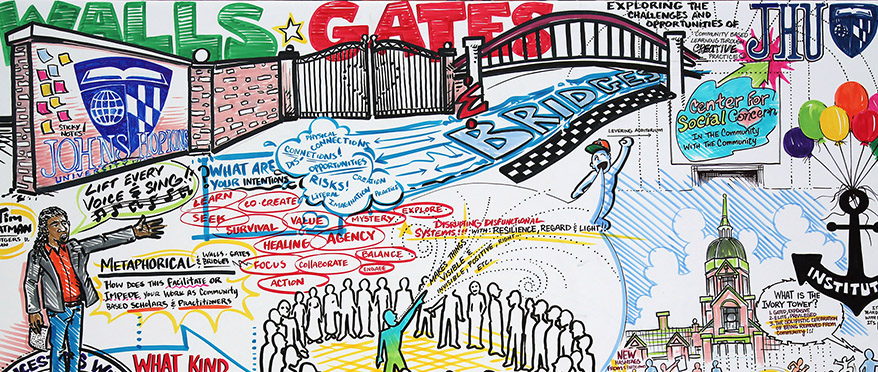

The following is a guest post by Jennifer Bernstein, Lecturer, Center for Leadership Education, Whiting School of Engineering, Johns Hopkins University.

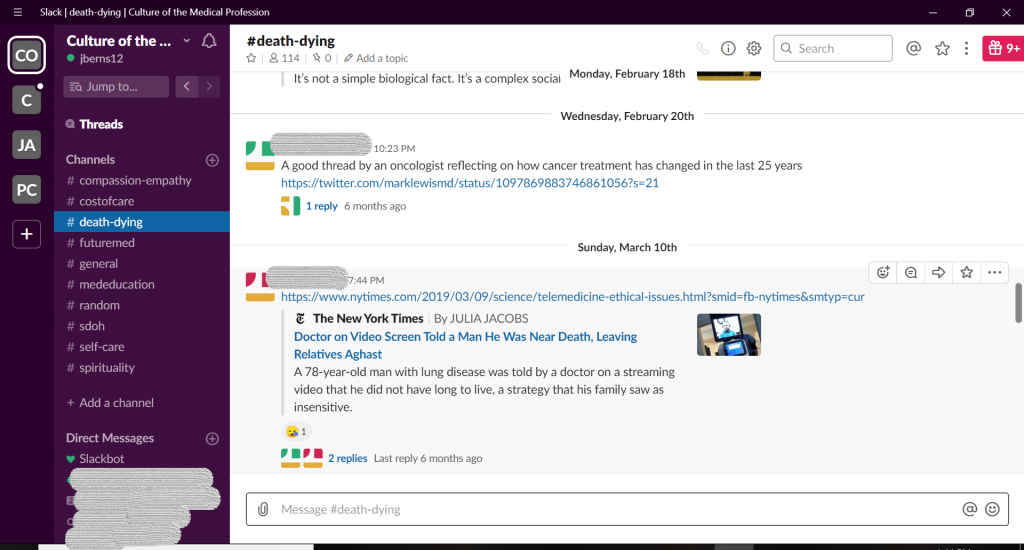

The culture of the medical profession is continually evolving; issues ranging from the cost of health care to demographic changes are just some of the factors influencing the culture surrounding medical professionals in the United States. As an instructor in this field, it is imperative to keep things as current for students as possible. In my class, Culture of the Medical Profession, I am constantly integrating new content from the news, twitter feeds, Instagram, and other sources. When newsworthy items arise, which is multiple times per week, I need to be able to notify students about these developments quickly and efficiently. I also want to spark conversation among the students about these developments as they happen. In Blackboard, where much of my course content resides, the synchronous communication tools available do not offer me an effective solution to keeping students informed and up-to-date; I find posting new content in Blackboard cumbersome and time-consuming, and the chat areas offer little interest when compared with commonly used platforms like Twitter.

Most of the students in my Culture of the Medical Profession class are in the pre-professional program and are planning to go on to medical school, dental school, or some other clinical training program. One of the course goals is for students to explore challenges faced by health professionals on a daily basis and why they are relevant for students considering a life in medicine; following the ongoing conversations about these challenges provides students with an awareness of what issues they may face once they commit to the field. Another goal is to provide students with a platform to communicate their own thoughts and ideas about these issues with me and with each other. In addition to the benefits of being exposed to various perspectives on each of the issues, this exercise helps students learn to clearly convey their ideas and findings to various professional audiences. I need a tool that will accommodate both of these goals: a way to immediately share relevant current events and enable students to effectively communicate about them.

About three years ago, I discovered Slack, an online communication tool used for project management and information sharing. I was on a joint JHU-MIT research team that was using it and soon came to realize how easy it was to synchronously and asynchronously communicate and share resources with other members of the group. In particular, we had fun sharing relevant news items, commenting on those items, or leaving emojis when we were short on time. Slack seemed like a natural fit for my class so I decided to give it a try.

I created a workspace in Slack for my class, which was separate from my research workspace. Slack workspaces are organized into ‘channels’ which are similar to chat rooms dedicated to specific topics. In my case, I created a channel for each topic on my syllabus. The names of channels are preceded by hash tags (e.g., #mededucation, #costsofcare, etc.). Once the Slack space was set up, I walked students through the mechanics of using it. Many of them had used it before and/or currently had their own accounts because they work in research labs and other academic environments that commonly utilize Slack, so they caught on quickly.

I let students know at the beginning of the term that their participation in Slack would count towards their overall participation grade. Two to three times each week I posted articles, tweets, etc. and provided brief commentary on the relevance. I posted not only in whatever channel/topic we were currently studying but also across the other hashtags. Students almost immediately responded with their own articles, reactions, links, etc. Sometimes the online discussions were so lively that they continued into our next face-to-face class meeting. Students also realized they could have conversations with individuals, separate from the group, so there were often several side conversations going on at the same time.

Since using Slack, the level of engagement in online class discussions has been consistently high. Students post to channels on their own, unprompted. Many of the issues covered in class are controversial and not always easy to talk about face to face. Slack provides a safe space to discuss and consider various perspectives of these issues; I’ve noticed that it also gives the quieter students an outlet to participate more confidently.

Community building has also been enhanced by using Slack. In general, I structure my classes so that about half of the time is lecture-based and the other half is some sort of group activity. Because of their frequent interactions on Slack, students now get to know one another beyond the small groups they are assigned to during class. Out of class, they slack each other relevant articles, links, etc. pertaining to whatever project they’re working on.

Community building has also been enhanced by using Slack. In general, I structure my classes so that about half of the time is lecture-based and the other half is some sort of group activity. Because of their frequent interactions on Slack, students now get to know one another beyond the small groups they are assigned to during class. Out of class, they slack each other relevant articles, links, etc. pertaining to whatever project they’re working on.

Feedback from previous students about Slack has been very positive; because of the continuous, up-to-date exposure to various issues in the medical field and the opportunity to communicate about them, students report feeling much more confident and prepared for medical school interviews. According to students, interviewers have been very impressed with their knowledge, passion, and level of commitment.

A few of my previous students, now currently in their gap year or training, continue to participate in the course’s Slack space because they want to keep up with current issues. This has been extremely beneficial to myself and my current students. As an instructor, it allows me to check in with them to see if there are any changes I should consider making to the course. For current students, it’s a connection to someone in the field, with an authentic perspective.

On the administrative side of things, Slack has definitely saved me time and frustration. It’s a snap to add/update links and notify students of any changes. There are also features that allow instructors to track student participation, if desired. Instructors can opt-in to an automatically generated weekly summary of usage statistics showing how many messages were posted, etc. There is also a powerful search feature in Slack which allows instructors to search and view posts made by individual students. If a discussion happens to get out of hand, instructors (as owners of a Slack space) have the ability to delete inappropriate posts and close it down if necessary.

Instructors have a range of options as they consider how to effectively communicate and share information with their students. Slack is working very well in my class of 19-25 students, but I recognize that it may not be the best tool for all classes. Instructors with large lecture classes, for example, might be challenged to use it effectively. Although I’m not there yet, I’m trying to figure out ways to use Slack in my other classes. In the meantime, it challenges me to make sure students in Culture of the Medical Profession see the relevance of the class beyond just an academic exercise and realize its value in their life’s work and experiences.

Jennifer Bernstein, Lecturer

Center for Leadership Education, Johns Hopkins University

Jennifer Bernstein is a lecturer in the Center for Leadership Education and has 20 years of experience working on WHO-, industry-, U.S. government-funded research studies and clinical trials. She is an alum of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and teaches a number of courses including Culture of the Medical Profession and Technical Writing.

Image Source: Pixabay, Jennifer Bernstein