As with many of our Innovative Instructor posts, this one was prompted by an inquiry from an instructor looking for resources, in this case for teaching international students. Johns Hopkins, among other American universities, has increased the number of international students admitted over the past ten years, both at the graduate and undergraduate level. These students bring welcome diversity to our campuses, but some of them face challenges in adapting to American educational practices and social customs. Fluency in English may be a barrier to their academic and social success. Following are three articles and an online guide that examine the issues and provide strategies for faculty teaching international students.

First up, a scholarly article that both summarizes some of the past research on international students and reports on a study undertaken by the authors: Best Practices in Teaching International Students in Higher Education: Issues and Strategies, Alexander Macgregor and Giacomo Folinazzo, TESOL Journal, Volume 9, Issue 2, June 18, 2018, pp. 299-329. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesj.324 “This article discusses an online survey carried out in a Canadian college [Niagara College, Niagara-on-the-Lake, Ontario] that identified academic and sociocultural issues faced by international students and highlighted current or potential strategies from the input of 229 international students, 343 domestic students, and 125 professors.” The study sought to address the challenges that international students face in English-language colleges and universities, understand the difference in the perceptions of those challenges among faculty, domestic students, and the international students themselves, and suggest strategies for improving learning outcomes for international students.

First up, a scholarly article that both summarizes some of the past research on international students and reports on a study undertaken by the authors: Best Practices in Teaching International Students in Higher Education: Issues and Strategies, Alexander Macgregor and Giacomo Folinazzo, TESOL Journal, Volume 9, Issue 2, June 18, 2018, pp. 299-329. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesj.324 “This article discusses an online survey carried out in a Canadian college [Niagara College, Niagara-on-the-Lake, Ontario] that identified academic and sociocultural issues faced by international students and highlighted current or potential strategies from the input of 229 international students, 343 domestic students, and 125 professors.” The study sought to address the challenges that international students face in English-language colleges and universities, understand the difference in the perceptions of those challenges among faculty, domestic students, and the international students themselves, and suggest strategies for improving learning outcomes for international students.

International students need to know technical terms (and other vocabulary) and concepts to succeed, but complex cultural mores may hinder them from seeking assistance when needed and they may be reluctant to speak in class. These barriers exist even among students with high TOEFL (Test of English as a Foreign Language) scores. Unfamiliarity with American pedagogical practices, such as classroom participation and active learning, along with lack of awareness of American social rules and skills may further isolate these students.

The researchers used an online survey to identify the challenges that international students face and to suggest solutions. Key points in the findings include: 1) international students feel the area they most need to improve is proactive academic behavior, rather than language skills per se; 2) a lack of clarity on academic expectations of assessments and assignments hinders their success; 3) both faculty and domestic students feel that some accommodations for international students are appropriate (e.g., dictionary use in class and during exams, extra time for exams, lecture notes given out before class).

The authors conclude that “IS [International Student] input suggests professors could respond by providing clear guidelines for task expectations, aims, and instructions in multisensory formats (simplify the message without changing the material), clarifying content/format expectations with exemplars, and collecting exemplars of outstanding student work and substandard student work from past terms and using them as examples to clarify expectations.” The authors suggest faculty provide opportunities for language development, create a positive classroom climate, become informed about their students’ cultures, avoid fostering fear of error, reinforce students’ strengths, and emphasize the importance of office hours.

An article from Inside Higher Ed, Teaching International Students, Elizabeth Redden, December 1, 2014, looks at the challenges for institutions of higher education and their instructors in teaching international students and the implications for classroom “dynamics and practices”.

The author interviewed faculty at the University of Denver on the challenges they faced in teaching international students. Plagiarism is mentioned as a problem in some cases due to different practices in other countries. English as a second language (ESL) barriers were cited by a professor of classics and humanities, who has made an effort to teach a first-year seminar that compares Chinese and Western classical literature in order to bridge the cultural gap.

Faculty at University of Denver have pushed the administration to change admission policies in regards to the TOEFL, raising the score requirements. “In addition, Denver now requires admitted students who are non-native English speakers to take the university’s own English language proficiency test upon arrival. Despite having already achieved the standardized test scores required for admission, students who score poorly on Denver’s assessment may be required to enroll full-time in the university’s English Language Center before being allowed to begin their degree program.” This has meant potentially losing international students to competing undergraduate programs, but the school wanted to make sure that its students had a positive classroom experience.

Several faculty describe courses they have taught that “…will serve to enhance the quality of education by creating the opportunity for more cross-cultural conversations and a kind of perspective-shifting.” This is an ideal situation, of course, and not all instructors have the flexibility to create new courses to take advantage of global viewpoints. None-the-less there are other strategies University of Denver faculty shared to improve learning experiences for international students, as well as their domestic counterparts.

Students may self-segregate themselves when seated in the classroom, so breaking up cultural groups and ensuring that students work across nationalities is important. Instructors should be aware that cultural references, slang, and idioms may not be understood by international students. Careful use of PowerPoint slides to reinforce course concepts, and sharing those slides with all students, ideally in advance of class, is recommended. Learn students’ names and how to pronounce them correctly. Learn something about their countries and cultures. “Professors talked about priming non-native speakers in various ways so they would be more apt to participate in class discussions, whether by allowing students to prepare their thoughts in a homework or in-class writing assignment, starting off class with a think-pair-share type activity, or appointing a different student to be a discussion leader each week.” The University of Denver Office of Teaching and Learning provides a web-page on Teaching International Students with helpful advice. Many of these recommendations are best practices for all students.

The article addresses the issues of consistency of standards and assessment. The consensus is that standards must be applied across the board to English-speakers and ESL-speakers alike. Writing assignments are particularly challenging. Doug Hesse, professor and executive director of the writing program at Denver notes that gaining fluency in writing for non-natives may take five to ten years. What, then, are fair expectations in terms of grading writing assignments?

“Hesse emphasizes the need to distinguish between global problems and micro-level errors in student writing. He isolates three dimensions of student writing: ‘aptness of content and approach to the task,’ ‘rhetorical fit,’ and ‘conformity to conventions of edited American English.’ He advises that professors ‘read charitably,’ reading for ‘content and rhetorical strategy’ as much as — or, actually, even prior to — reading for surface errors.” Hesse concedes that if the errors interfere with comprehension, that’s a problem, but he focuses his attention on content and approach. And he recommends “…sharing models for writing assignments, spending class time generating ideas for a paper, reading a draft and offering feedback, and structuring long projects in stages.” These, like the suggestions above, will be beneficial to all students. The University of Denver Writing Program offers a set of Guidelines for Responding to the Writing of International Students.

The University of Michigan, Center for Research on Teaching and Learning offers Teaching International Students: Pedagogical Issues and Strategies, another useful web guide for instructors. While some of the materials are specific to University of Michigan faculty, the topics Bridging Differences in Background Knowledge and Classroom Practice, Teaching Non-Native Speakers of English, Improving Climate, and Promoting Academic Integrity will be useful to all instructors.

If the deep dive of the first two articles is more than you are looking for, Teaching International Students: Six Ways to Smooth the Transition, Eman Elturki, Faculty Focus, June 29, 2018, cuts straight to the chase with practical tips. In a nutshell:

- Communicate classroom expectations and policies clearly.

- Encourage students to make use of office hours.

- Discuss academic integrity.

- Make course materials available.

- Demystify assignment requirements.

- Incorporate opportunities for collaborative learning.

More detail is provided on implementing these suggestions. Elturki sums up by repeating advice similar to that of the faculty at University of Denver, “…pursuing higher education in a foreign country can be challenging. Being mindful of international students in your classroom and incorporating ways to help them adapt to the new educational system can reduce their stress and help them succeed. In fact, adopting these practices have the potential to help all students, whether they grew up in the next town over or the other side of the globe.”

Macie Hall, Senior Instructional Designer

Center for Educational Resources

Image Source: Pixabay.com

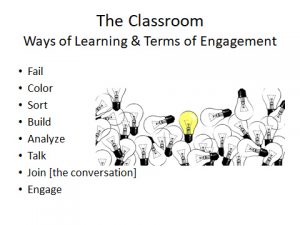

but the support faculty can provide for students in the classroom. Two previous posts, Scaffolding Part 2: Build Your Students’ Notetaking Skills (March 29, 2017) and Scaffolding: Teach your students how to read a journal article (February 28, 2017) looked at ways in which instructors can give students a framework to improve their skills and help them succeed. In an article in the Chronicle of Higher Education, Traditional Teaching May Deepen Inequality. Can a Different Approach Fix It? (Beckie Supiano, May 6, 2018) instructor Kelly A. Hogan asks, “Doesn’t everybody like some structure or guidance? Why do we treat learning as something different or special?”

but the support faculty can provide for students in the classroom. Two previous posts, Scaffolding Part 2: Build Your Students’ Notetaking Skills (March 29, 2017) and Scaffolding: Teach your students how to read a journal article (February 28, 2017) looked at ways in which instructors can give students a framework to improve their skills and help them succeed. In an article in the Chronicle of Higher Education, Traditional Teaching May Deepen Inequality. Can a Different Approach Fix It? (Beckie Supiano, May 6, 2018) instructor Kelly A. Hogan asks, “Doesn’t everybody like some structure or guidance? Why do we treat learning as something different or special?”

Our last two posts have focused on diversity and inclusion in the classroom. Today I’d like to offer some resources for another important way to create a positive classroom climate: knowing your students’ names and pronouncing them correctly. A previous post

Our last two posts have focused on diversity and inclusion in the classroom. Today I’d like to offer some resources for another important way to create a positive classroom climate: knowing your students’ names and pronouncing them correctly. A previous post