The return to in-person teaching last year brought with it a high degree of uncertainty for students and faculty. Professors reported that stress, fatigue, and anxiety contributed to higher levels of student disengagement, disconnection, and languishing than in pre-pandemic courses.  Faculty at other schools reported similar trends with several articles and essays published in the NY Times and Chronicle of Higher Education over the past several months. At faculty’s request, the Center for Teaching Excellence and Innovation (CTEI) hosted a discussion for instructors to share their experiences and brainstorm solutions for Fall 2022 and beyond. Over thirty instructors participated. Brian Cole, Associate Director of the CTEI, moderated the discussion.

Faculty at other schools reported similar trends with several articles and essays published in the NY Times and Chronicle of Higher Education over the past several months. At faculty’s request, the Center for Teaching Excellence and Innovation (CTEI) hosted a discussion for instructors to share their experiences and brainstorm solutions for Fall 2022 and beyond. Over thirty instructors participated. Brian Cole, Associate Director of the CTEI, moderated the discussion.

Faculty attendees reported that students seemed to struggle transitioning from online classes to in-person classes last spring. One person shared that colleagues at other institutions were reporting the same concerns. The behaviors described included students:

- expressing concerns about being prepared for high-stakes exams

- regularly being distracted by devices during class

- skipping class more frequently than before the pandemic

- requesting more mental health accommodations

- acting more aggressively toward instructors (One instructor said this behavior is more likely seen by instructors of certain races and gender.)

Participants felt these behaviors could be traced to several sources. The pandemic was traumatic for many students suffering from social isolation and the stress of living under the threat of COVID. Faculty also felt some students were not as prepared for their classes because pre-requisite college classes or high school courses were online and employed pass-fail grading schemas. Other instructors reported students feeling stressed about other global events (e.g., political polarization, Ukraine war). While the pandemic may be fading or becoming normalized, faculty shared that other stressors are constants that continue to weigh on students.

This led to a discussion about when it was appropriate for faculty to engage students about their stress and anxiety over global crises. Instructors teaching in the social sciences can more easily integrate discussions of current events into their curriculum. Is it appropriate for faculty in science and engineering to dedicate class time to social stressors that affect students? Most participants said yes. Several shared they provide opportunities for students to talk about current events that may impact them and ask students openly, “How are you doing? What’s going on with your peers?” to give them space to talk.  Several faculty participants asked for advice on how to set boundaries on the amount of time to dedicate to these discussions during class and what types of topics to discuss. Those that dedicate class time to talking about global issues or student mental health concerns felt it was appropriate to occasionally dedicate 15 minutes of class time to connect with students and build relationships with them. As for topics, instructors should choose topics they are comfortable discussing.

Several faculty participants asked for advice on how to set boundaries on the amount of time to dedicate to these discussions during class and what types of topics to discuss. Those that dedicate class time to talking about global issues or student mental health concerns felt it was appropriate to occasionally dedicate 15 minutes of class time to connect with students and build relationships with them. As for topics, instructors should choose topics they are comfortable discussing.

Another source of stress mentioned was the number of hours students are working. One professor shared he has seen an increase in students trying to work full time while attending school. It’s not a large number, but definitely an increase that was likely precipitated by the flexible schedules during COVID when classes were more likely to be asynchronous. Another instructor shared that she observed an increase in students working part-time jobs during COVID. She felt it was important to be more explicit with students about expectations for deadlines and the time it takes to complete assignments to help students balance working outside of class. However, many participants felt it was not appropriate for students to work full-time. Another instructor reported an increase in students continuing summer internships into the academic year. Students see this as a pathway to a job after graduation and are motivated to continue working. This may be a good opportunity, but again, faculty are concerned students are overcommitted.

Some faculty record their lectures for students to review later, while others questioned if this would result in students skipping class. Several faculty responded with strategies to encourage students to attend. These included using activities that motivate students to show up and awarding points for participating in those activities. One instructor said he records the videos, but shares them with students only upon request. If a student is regularly requesting them and not showing up for class, he engages them to learn more about why they are skipping to address any issues. He shares all of the videos with students the week before the exam. Another instructor said she has recorded her lectures for 15 years, and uses activities to encourage student attendance and engagement with each other. She stresses, “I’m not the only person in the room. You also learn from the other students when you are here.”

Another instructor asked if recording the class discourages students from asking questions. Two instructors responded it did not affect behavior in their classes, but that could be because they teach large courses so students are generally less likely to ask questions during class meetings.

While the pandemic was stressful for everyone, faculty reported it provided opportunities to experiment with new teaching strategies. Many are now trying to evaluate which changes to keep or drop. One instructor said their decision is based on the time required to implement the strategy and its impact on student learning. Another instructor said she offered more low-stakes assessments while teaching online. She felt this helped reduce the stress of high-stakes assessments, but she is now considering if she is requiring too much of students. The value of offering more low-stakes assessments is that students get more regular feedback throughout the semester.

Another instructor said she offered more low-stakes assessments while teaching online. She felt this helped reduce the stress of high-stakes assessments, but she is now considering if she is requiring too much of students. The value of offering more low-stakes assessments is that students get more regular feedback throughout the semester.

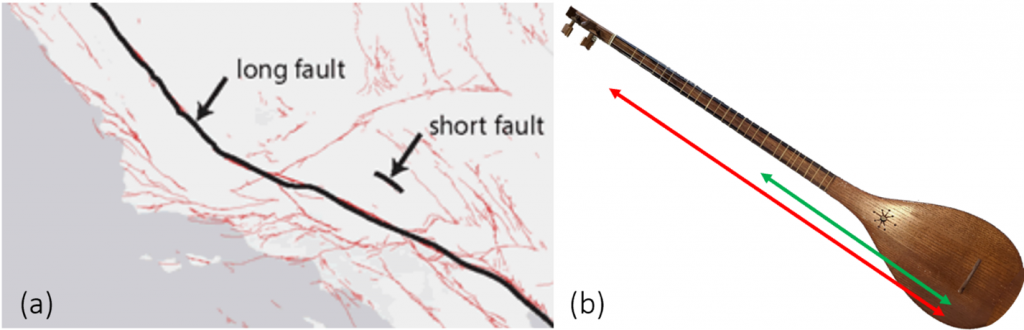

Another instructor is hearing from students that instructors are assigning more applied learning assignments that leverage technology (e.g., arcGIS) which require significantly more time to complete. While it’s good to have interdisciplinary projects and collaborate with other groups, such as data services at the university, we need to remember that this also requires students to work with different groups and learn additional skills, all of which take time.

Overall, faculty felt the goal is not to penalize disengagement, but to encourage students to engage. Faculty participants shared additional strategies to address student disengagement which are summarized below:

- Eliminate online tools for the course that are not critical.

- Offer asynchronous work days. This is not an off day, but a chance to work on class assignments. One instructor shared that students really liked having a day to work on their projects.

- Clearly communicate expectations for class (e.g., assignment deadlines, pre-class work expectations) on a regular basis and in multiple modalities (e.g., verbally in class, on Canvas, via class email).

- Build in flexibility to assignment deadlines. One instructor allows students to skip up to two assignments, and their grade is replaced by the average of the existing assignments.

- Another instructor shared a similar approach: she does not permit any extensions on homework even if a student is sick, however, she replaces missing grades with the average of the other assignments if the student presents a viable excuse for missing the deadline. The instructor uses this approach because it allows her to share the homework solutions immediately after the deadline while students are still intellectually engaged with the assignment.

- Another instructor builds in quizzes related to the homework to encourage students to look at it early. For example, the day after homework is posted, students are presented with a quiz asking them to describe what the homework is asking them to do. They don’t need to solve it, but it motivates them to look at it early instead of waiting until the last day when they will have less time to get help.

- Consider using the discussion board in Canvas or encourage students to attend office hours if you don’t want to dedicate class time to check in with them.

- Share wellness resources from JHU including the Student Well-being blog about talking with students about current events: https://wellbeing.jhu.edu/blog/. They also provide a page for dealing with more acute issues when students are in distress: https://wellbeing.jhu.edu/resources/faculty-staff/

- Consider limiting the use of devices (phones, laptops, etc.) to minimize distractions during class.

- Share mental health resources with your students including Mental Telehealth (free counseling via video chat), Calm app (great for sleep, focus, mindfulness), A Place to Talk (peer listening), Stress and Depression Questionnaire (10minute confidential assessment with feedback w/in 48 hours from a Hopkins clinician).

- Share how you manage your stress to demonstrate that students are not the only ones dealing with these issues. One participant said, “We might feel it, but if we don’t say it, they don’t know it. If you talk about it, then you open up a space for students to talk about their own stressors.”

- Consult inclusive teaching practices and Hopkins Universal Design for Learning resources which can help instructors build flexibility into their teaching. One instructor said that being flexible includes building in processing time to help students prepare for their assignments. This includes emotional processing time on difficult topics.

Clare Lochary from the Office of Student Health and Wellbeing shared that the Counseling Center sees two clear spikes in incoming clients each semester. The first is six weeks into the semester when students begin to realize they aren’t doing as well as they want in their courses. The second is during the last two weeks of the semester as they prepare for final papers and exams. Faculty should be aware of these cycles and pay special attention to student behavior so they can refer students to help resources or address concerns about academic performance.

Clare Lochary from the Office of Student Health and Wellbeing shared that the Counseling Center sees two clear spikes in incoming clients each semester. The first is six weeks into the semester when students begin to realize they aren’t doing as well as they want in their courses. The second is during the last two weeks of the semester as they prepare for final papers and exams. Faculty should be aware of these cycles and pay special attention to student behavior so they can refer students to help resources or address concerns about academic performance.

Mike Reese

Mike Reese is Associate Dean of the Center for Teaching Excellence and Innovation and associate teaching professor in Sociology.

Image Source: Unsplash