With good reason, one of the most common strategies that instructors turn to in the classroom is assigning students to work collaboratively in groups. Group work, when thoughtfully designed and facilitated, can be a very effective way to engage students in their learning. Though not without challenges, group work offers numerous benefits:

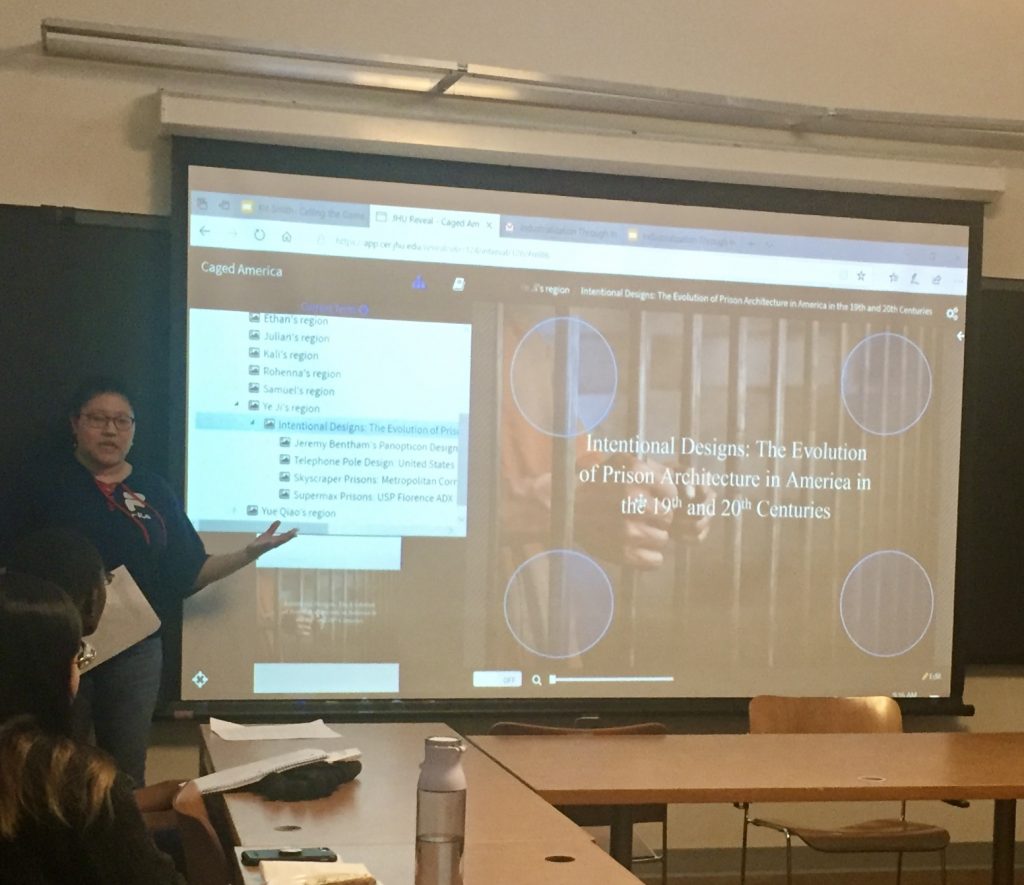

- Increased engagement: Group work promotes active engagement and collaboration among students, which can help build a sense of community in the classroom. The learning process becomes more interactive which can deepen the level of understanding of course material and positively impact classroom dynamics.

- Diverse perspectives: Group work encourages the exchange of diverse ideas and perspectives.

This can lead to a richer learning environment as students are exposed to different viewpoints and alternative solutions to problems.

This can lead to a richer learning environment as students are exposed to different viewpoints and alternative solutions to problems. - Skill development: Working in groups, students acquire a range of skills, including communication, problem-solving, and leadership skills. While certainly relevant in academia, these skills can also help students prepare for a professional work environment, where teamwork and collaboration are essential.

Simply dividing your students into groups with little or no direction is unlikely to lead to the best outcome. Incorporating group work into courses requires careful planning and clear guidelines to ensure its effectiveness. The following is a list of strategies to consider when facilitating group work:

Group formation:

- Consider aligning students with complementary or diverse skill sets. A broad range of skills often leads to creative ways of approaching and solving problems. Administering a survey to students before the project begins can help determine academic disciplines, backgrounds, and relevant skill levels.

- When possible, avoid isolating underrepresented minorities in groups. For example, place 0, 2, or 3 women in a team when forming groups of 3 (i.e., do not create a team of 1 woman and 2 men). This helps prevent the underrepresented from being over-ruled or ignored (Rosser, 1998).

- Explore technology options. If using a learning management system (LMS) such as Canvas, it will often include a tool to assist with creating and managing groups. Outside of the LMS, there is a free, open-source tool called gruepr that can assist instructors with group creation. CATME is another tool that assists with group creation and peer review. We reviewed CATME several years ago when it was free, but there is now a fee for use.

Team Interaction:

- Establish ground rules for groups: insist on civil dialogue, respect others’ opinions, listen actively, etc. Involving students in creating the rules helps them hold each other accountable throughout the process. Carnegie Mellon has a resource with suggestions for setting ground rules that may be helpful for instructors.

- Assign each student a different role in the group and rotate the roles frequently. This helps to ensure that work is distributed equally throughout the project, avoiding situations where a few students are doing all the work while others are just along for the ride (Finelli et all., 2011). Examples of roles include recorder, spokesperson, summarizer, organizer, observer, timekeeper, or liaison to other groups. Be sure each role has specific tasks that are clearly laid out for students.

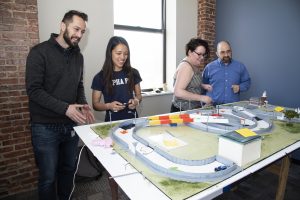

- Include one or more short, introductory warm-up activities for group members to engage and get to know one another. This will help to build rapport and encourage participation within the group.

- Consider the physical space if allowing students to work in groups during class. Is the room conducive/comfortable for small groups to convene? Will students need accommodations? If teaching online, are groups meeting synchronously or asynchronously? Plan accordingly to anticipate space and technology needs.

Assessment:

- Determine how you will assess the project. Depending on the goals, consider assessing both group and individual contributions. Develop and share rubrics with students so they know exactly what is expected. This sample group work rubric from Carnegie Mellon can be used as a guide.

- Meet regularly with each group to monitor progress. Set milestones to help students stay on track and meet their goals.

- Include opportunities for self and peer assessment. Self-assessment encourages critical thinking and fosters greater self-awareness in student learning. Peer assessment provides valuable insight for instructors about group dynamics and performance. It can also serve to motivate students to take responsibility for their individual tasks. Be sure to clarify for students if self and peer assessment will count towards their grade. This assessment form from Carnegie Mellon is designed for students to assess themselves as well as group members.

- Allow time for reflection. Asking students to reflect on the process can help them extract meaningful lessons from the project’s successes and challenges. It can also promote a deeper understanding of the project’s goals and the collaborative process as a whole. Examples of reflective exercises include written responses to specific prompts (i.e. what went well, what could be improved, etc.), small group or whole class discussions, and keeping a journal of the learning experience. More information about group reflection can be found in this resource from the University of New South Wales.

With proper planning, group projects can be a positive and productive learning experience that will help prepare students for real-world challenges. Do you have additional tips to share about group facilitation? Please share them in the comments.

Amy Brusini, Senior Instructional Designer

Center for Teaching Excellence and Innovation

Image source: Pixabay

References:

Finelli, C., Bergom, I., & Mesa, V. (2011). Student teams in the engineering classroom and beyond: setting up students for success. Center for Research on Learning and Teaching: University of Michigan. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED573963.pdf

Rosser, S. V. (1998). Group work in science, engineering, and mathematics: Consequences of ignoring gender and race. College Teaching, 46(3), 82-88.

University of New South Wales. (n.d.) Supporting students to reflect on their group work. https://www.teaching.unsw.edu.au/helping-students-reflect-group-work

Washington University of St. Louis, Center for Teaching and Learning. (n.d.) Facilitating in-class group work. https://ctl.wustl.edu/resources/facilitating-in-class-group-work/