Designing effective assessments is a critical part of the teaching and learning process. Instructors use assessments, ideally aligned with learning objectives, to measure student achievement and determine whether or not they are meeting the objectives. Assessments can also inform instructors if they should consider making changes to their instructional method or delivery.

Assessments are generally categorized as either summative or formative. Summative assessments, usually graded, are used to measure student comprehension of material at the end of an instructional unit. They are often cumulative, providing a means for instructors to see how well students are meeting certain standards. Instructors are largely familiar with summative assessments. Examples include:

- Final exam at the end of the semester

- Term paper due mid-semester

- Final project at the end of a course

In contrast, formative assessments provide ongoing feedback to students in order to help identify gaps in their learning. They are lower stakes than summative assessments and often ungraded. Additionally, formative assessments help instructors determine the effectiveness of their teaching; instructors can then use this information to make adjustments to their instructional approach which may lead to improved student success (Boston). As discussed in a previous Innovative Instructor post about the value of formative assessments, when instructors provide formative feedback to students, they give students the tools to assess their own progress toward learning goals (Wilson). This empowers students to recognize their strengths and weaknesses and may help motivate them to improve their academic performance.

instructors determine the effectiveness of their teaching; instructors can then use this information to make adjustments to their instructional approach which may lead to improved student success (Boston). As discussed in a previous Innovative Instructor post about the value of formative assessments, when instructors provide formative feedback to students, they give students the tools to assess their own progress toward learning goals (Wilson). This empowers students to recognize their strengths and weaknesses and may help motivate them to improve their academic performance.

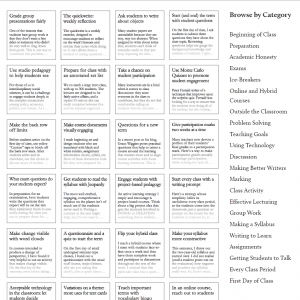

Examples of formative assessment strategies:

- Surveys – Surveys can be given at the beginning, middle, and/or end of the semester.

- Minute papers – Very short, in-class writing activity in which students summarize the main ideas of a lecture or class activity, usually at the end of class.

- Polling – Students respond as a group to questions posed by the instructor using technology such as iclickers, software such as Poll Everywhere, or simply raising their hands.

- Exit tickets – At the end of class, students respond to a short prompt given by the instructor usually having to do with that day’s lesson, such as, “What readings were most helpful to you in preparing for today’s lesson?”

- Muddiest point – Students write down what they think was the most confusing or difficult part of a lesson.

- Concept map – Students create a diagram of how concepts relate to each other.

- First draft – Students submit a first draft of a paper, assignment, etc. and receive targeted feedback before submitting a final draft.

- Student self-evaluation/reflection

- Low/no-grade quizzes

Formative assessments do not have to take a lot of time to administer. They can be spontaneous, such as having an in-class question and answer session which provides results in real time, or they can be planned, such as giving a short, ungraded quiz used as a knowledge check. In either case, the goal is the same: to monitor student learning and guide instructors in future decision making regarding their instruction. Following best practices, instructors should strive to use a variety of both formative and summative assessments in order to meet the needs of all students.

References:

Boston, C. (2002). The Concept of Formative Assessment. College Park, MD: ERIC Clearinghouse on Assessment and Evaluation. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED470206).

Wilson, S. (February 13, 2014). The Characteristics of High-Quality Formative Assessments. The Innovative Instructor Blog. http://ii.library.jhu.edu/2014/02/13/the-characteristics-of-high-quality-formative-assessments/

Amy Brusini

Senior Instructional Designer

Center for Educational Resources

Image Source: Pixabay

Our last two posts have focused on diversity and inclusion in the classroom. Today I’d like to offer some resources for another important way to create a positive classroom climate: knowing your students’ names and pronouncing them correctly. A previous post

Our last two posts have focused on diversity and inclusion in the classroom. Today I’d like to offer some resources for another important way to create a positive classroom climate: knowing your students’ names and pronouncing them correctly. A previous post  Innovative Instructor post

Innovative Instructor post