This past spring, the Classics Department launched the Classics Research Lab (CRL). Within each CRL iteration, students conduct empirical research with faculty, contributing to a larger, ongoing project. Although the research takes place under the umbrella of a course, it is the larger project that dictates the course’s scope and even duration—extending, if needed, across multiple semesters. The initiative is similar, in some ways, to a traditional science lab course in which students carry out set experiments to learn disciplinary content and skills. But it differs in that CRL research is open-ended and discovery-based; assisting faculty with an authentic research project, students make new observations and original interpretations of the data under consideration. The guiding principle of the CRL is that undergraduate students should have the opportunity to experience the real, hands-on work of the humanities: to engage in the active questions that humanist scholars pursue, to recognize the historical and current stakes of those questions, and to add their labor, as increasingly competent collaborators, to the quest for answers through careful, detailed, discipline-specific research.

This past spring, the Classics Department launched the Classics Research Lab (CRL). Within each CRL iteration, students conduct empirical research with faculty, contributing to a larger, ongoing project. Although the research takes place under the umbrella of a course, it is the larger project that dictates the course’s scope and even duration—extending, if needed, across multiple semesters. The initiative is similar, in some ways, to a traditional science lab course in which students carry out set experiments to learn disciplinary content and skills. But it differs in that CRL research is open-ended and discovery-based; assisting faculty with an authentic research project, students make new observations and original interpretations of the data under consideration. The guiding principle of the CRL is that undergraduate students should have the opportunity to experience the real, hands-on work of the humanities: to engage in the active questions that humanist scholars pursue, to recognize the historical and current stakes of those questions, and to add their labor, as increasingly competent collaborators, to the quest for answers through careful, detailed, discipline-specific research.

A second aim of the CRL is to counter prevailing myths about humanities research by making it more visible and accessible to non-specialists. Accordingly, CRL participants meet and work in a public lab space—a room in Gilman Hall that looks out onto the atrium. CRL work-in-progress is visible through the windows of the Lab as well as online, via the websites built by individual projects. (See, for example, https://symondsproject.org/.)

The pilot CRL project, co-taught by Shane Butler of the Classics Department and Gabrielle Dean of the Sheridan Libraries, focused on John Addington Symonds, a Victorian scholar who wrote a groundbreaking work on Ancient Greek sexuality, A Problem in Greek Ethics. In its first semester, the John Addington Symonds Project (JASP) produced outcomes that not only contribute to a richer narrative about the history of sexuality, showing how Symonds painstakingly built his innovative arguments, but also provide future researchers with a new set of tools. Along the way, students acquired key skills in bibliography, archival and rare book research, and digital humanities.

The discovery-based ethos of the course required some significant departures from the usual pedagogical protocols. In place of a fixed syllabus, with all assignments configured and described in advance, the instructors developed a semi-structured syllabus with readings and preparatory assignments in the first half of the semester and a more open schedule in the second half of the semester. The goal was to empower students to help guide the project’s directions based on what they learned.

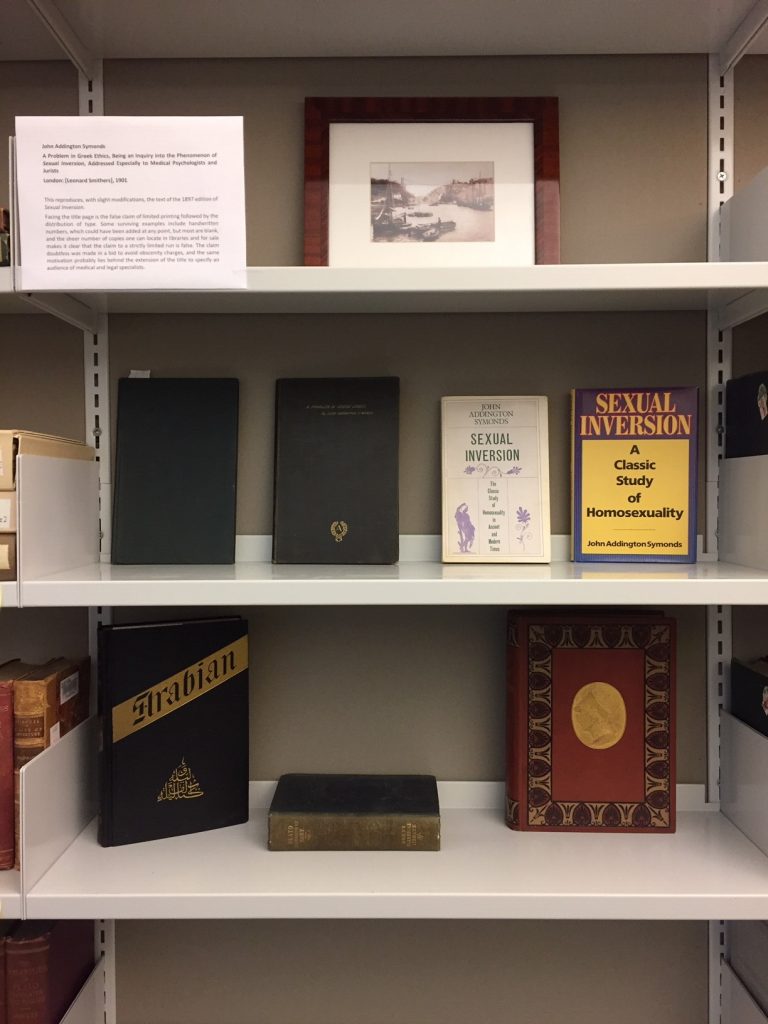

The semester started with a collaborative assignment designed to orient students to the topic and to the basic tasks of humanities research. Using Zotero, an open-source, digital reference management platform, students collectively assembled the Sheridan Libraries’ catalog records of books by Symonds. The books were then checked out to the Lab and shelved in its secure, dedicated space, so that students could work with them over the semester. Students also visited the Libraries’ special collections to study rare, non-circulating books. This initial assignment introduced students from a range of disciplines to library resources and humanities research processes, while offering a broad overview of Symonds’ writings and range of interests. At the same time, students read and discussed Symonds’ autobiography and signature works in the history of sexuality to ground them in the topic. And they began their independent investigations of books written and read by Symonds. Using the materials checked out to the Lab and in special collections, students composed short blog-style essays documenting the physical features of these books, relating the books to Symonds’ letters and other writings, and construing from their observations new analyses of Symonds’ bibliographic and social networks. These blog posts, after undergoing peer review and instructor review, have been published on the project website. (https://symondsproject.org/blog/)

The second collaborative project undertaken by JASP was an “index locorum” to A Problem in Greek Ethics—a detailed index of citations. Using digital resources and reference books checked out to the Lab, students retraced Symonds’ own research to identify the specific texts he used in the composition of this seminal essay. This brand-new index makes it startingly clear how Symonds connected a breadth of Greek and Latin sources, integrated works by later writers, and from these foundations drew original conclusions about the evolution of same-sex love, eroticism, and social norms and ideas about gender and sexuality in the ancient Greek and Roman worlds—as well as the legacy of these practices and philosophies. The index locorum, which is still in progress, is published on the JASP website. (https://symondsproject.org/greek-ethics-index/)

The index brought to the Project’s attention an important gap in Symonds scholarship: the absence of reliable digital editions of some versions of A Problem in Greek Ethics, which has a complicated publication history because of censorship and the practices that publishers undertook to evade it. In keeping with the CRL’s dedication to collaborative leadership, JASP participants decided to dedicate the second half of the semester to two linked endeavors.

- A new, accurate, digital edition of the 1897 edition of A Problem in Greek Ethics, an important edition because it was frequently republished. (https://symondsproject.org/greek-ethics-about/)

- A digital reconstruction of Symonds’ personal library in Omeka, an open-source content management system for digital collections. (https://symondsproject.org/library/)

Students also contributed to the visibility and ongoing viability of the lab through two “meta-lab” ventures: a video (still in development) about JASP, using footage captured throughout the semester via a camera set-up and workflow established by Reid Sczerba of the CER, and a manual documenting the Project’s research processes, to be used by future students. Finally, JASP hosted an “open lab” at the end of the semester with a display of rare books, facsimile photographs, and the physical manifestations of the reconstructed Symonds library, along with the chance to talk with students about their research. While the CRL will continue next semester with the John Addington Symonds Project, it is not constrained to that topic. Other faculty will offer their own lab courses, sometimes simultaneously in the lab space, to provide students with a variety of opportunities to apply humanities research skills.

While the CRL will continue next semester with the John Addington Symonds Project, it is not constrained to that topic. Other faculty will offer their own lab courses, sometimes simultaneously in the lab space, to provide students with a variety of opportunities to apply humanities research skills.

Professors Butler and Dean believe the research-based teaching model of the Classics Research Lab is a contemporary implementation of the historic Johns Hopkins model, as the first modern research university in America. The hope is that this curricular model might scale to other disciplines and other universities. For more information, contact Shane Butler (shane.butler@jhu.edu) or Gabrielle Dean (gnodean@jhu.edu).

Dr. Michael J. Reese, Associate Dean and Director

Center for Educational Resources

Image Source: Gabrielle Dean, Reid Sczerba

While tracking down some resources for active learning this past week, I stumbled on

While tracking down some resources for active learning this past week, I stumbled on