[Guest post by Anne-Elizabeth Brodsky, Senior Lecturer, Expository Writing, JHU]

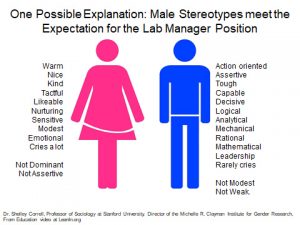

As part of the Lunch and Learn series, Karen Fleming (biophysics professor) and I gave presentations on fostering an inclusive classroom environment, summarized in the previous post.

In this follow up, I’ll offer some resources that seem to me versatile enough to use in different kinds of classrooms, and toward different ends. I’ve divided them into the categories below; the sources in the first three sections, in particular, can nearly all live quite comfortably in most disciplines.

What is college for?

Why bother with stories

How textual analysis works

Ideas for writing assignments

What is college for?

Plenty of college students, from visibly diverse backgrounds and otherwise, feel mystified by the academy, at best —and overwhelmed by it, at worst. One way I try to help them find their footing is to engage them in examining university culture.

Plenty of college students, from visibly diverse backgrounds and otherwise, feel mystified by the academy, at best —and overwhelmed by it, at worst. One way I try to help them find their footing is to engage them in examining university culture.

In my courses we use the sources below, and others, for informal “response writing.” I’m not using these sources to teach academic argument, although plenty of them have elegant arguments built into their narratives, and my students do notice that. I use them in hopes of activating their engagement and imagination about what their undergraduate experience will mean for them—to give them glimpses from the skybox.

Here’s a sampling:

Anna Deveare Smith raises the stakes of higher ed in her Chronicle interview “Are Students “Learning Anything About Love Here?’”

In “How to Live Wisely,” Richard J. Light describes the Harvard course “Reflecting on Your Life.” Students explore: What does it mean to live a good life? What about a productive life? How about a happy life? How might I think about these ideas if the answers conflict with one another? And how do I use my time here at college to build on the answers to these tough questions?”

Mark Edmundson, first in his family to go to college, takes on undergraduate experience at research institutions in “Who Are You and What Are You Doing Here?”

“The Cosmos and You,” just a few paragraphs long, tells the story of an astronomy student who asks her professor the big question: “How do you keep from despairing at the immensity of space and the smallness of us?”

Julio M. Ottino and Gary Saul Morson write about empathy, engineering, and more in “Building a Bridge Between Engineering and the Humanities.”

Neil Koblitz advocates for clear, engaging storytelling in the sciences in “Why STEM Needs the Humanities.”

Lyell Asher’s essay “Low Definition in Higher Education” takes on Anna Karenina, safe spaces, and more: “Rightly understood, the campus beyond the classroom is the laboratory component of college itself. It’s where ideas and experience should meet and refine one another, where things should get more complicated, not less.”

Nicholas Lemann’s “The Case for a New Kind of Core” proposes “a methods-based, rather than a canon-based, curriculum,” with skills categories: information acquisition, cause & effect, interpretation, numeracy, perspective, language of form, thinking in time, and argument.

“The Astrophysicist Who Wants to Help Solve Baltimore’s Urban Blight” tells the story of a Hopkins professor and the Baltimore Housing Commissioner teaming up to tackle our vacant housing problem.

Finally, a dated but still very popular article among my students is Thomas Friedman’s “How to Get a Job at Google.” To a person, every student who has read this has been surprised. At JHU as at many other schools, it’s common for students to see college as a means to an end—professional school, a big job. Living in the future tense, focused almost entirely on the retroactive value of college they plan to enjoy after graduation, they default to a safe, well-worn path of coursework and GPA management. Friedman’s article, like many of those above, nudges them a bit on this.

Why bother with stories

A central tenet of the Expository Writing Program at Hopkins is that our students engage in meaningful writing. Our students write to contribute to an ongoing intellectual conversation about a genuine problem or question. We expect students to think not only about their argument, based on the evidence at hand, but also about the implications of their argument.

A central tenet of the Expository Writing Program at Hopkins is that our students engage in meaningful writing. Our students write to contribute to an ongoing intellectual conversation about a genuine problem or question. We expect students to think not only about their argument, based on the evidence at hand, but also about the implications of their argument.

Thus if I’m asking students (in my classes, mostly STEM majors) to enter a critical conversation about a short story, I have to be sure we are explicit about how it could possibly matter whether or not they make a compelling argument about a piece of fiction—you know, something that never really happened.

So, in class we ask the question: Why bother with stories? Here are some resources that have helped answer this:

Short fiction warrants a column in the New York Times op-ed pages in David Brooks’ “The Child in the Basement,” which nicely models a summary (of Ursula Le Guin’s “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas”) and then offers three socially relevant readings of the text.

Diaa Hadid’s interview with Mahlia Lone and Laaleen Sukhera, “2 Sisters in Pakistan Find They Have a Lot in Common with Jane Austen” illustrates connections between upper-class contemporary Pakistan and the England of Austen’s novels.

Two TED talks: The well-known “The Danger of a Single Story” by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie and Raghava KK’s also wonderful 4½ -minute “Shake Up Your Story.”

Here’s an idea I haven’t tried yet: put Adichie’s talk next to John W. Krakauer and David Poeppel’s “Neuroscience Needs Behavior: Correcting a Reductionist Bias,” which is also about the “danger of a single story.”

Most recently: Lindy West writes in her op-ed “We Got Rid of Some Bad Men. Now Let’s Get Rid of Bad Movies”: “Art didn’t invent oppressive gender roles, racial stereotyping or rape culture, but it reflects, polishes and sells them back to us every moment of our waking lives.”

All of this depends on analysis, of course, and especially textual analysis…

How textual analysis works

There are lots of ways to teach students how to do textual analysis (aka close reading). A few favorite resources:

There are lots of ways to teach students how to do textual analysis (aka close reading). A few favorite resources:

“Twenty Titles: One Poem,” by poet Douglas Kearney, helps students see different interpretations (titles) of the same data (the sculpture).

Here, students analyze the poem “Since You Are Mortal” (Simonides) and then turn over the page to see how the translator, Danielle S. Allen, interprets it.

Danielle S. Allen, Our Declaration: A Reading of the Declaration of Independence in Defense of Equality (excerpts)

John Oliver, “Migrants and Refugees” (1:12-1:54)

NPR Code Switch Podcast: Camila Domonoske, “When ‘Miss’ Meant So Much More: How One Woman Fought Alabama — And Won”

Two more TED talks: John McWhorter’s “Txting is Killing Language. JK!!!” and Jean-Baptiste Michel and Erez Lieberman Aiden’s “What We Learned from 5 Million Books”

Ideas for writing assignments

Again, just a quick sampling of texts that have worked well with first- and second-year students. My colleagues have loads of their own, as you likely do as well.

Again, just a quick sampling of texts that have worked well with first- and second-year students. My colleagues have loads of their own, as you likely do as well.

Summarizing an academic article:

Lin Bian et al, “Messages About Brilliance Undermine Women’s Interest in Educational and Professional Opportunities”

Samantha P. Fan et al, “The Exposure Advantage: Early Exposure to a Multilingual Environment Promotes Effective Communication”

Martha C. Nussbaum, “Teaching Patriotism: Love and Critical Freedom”

Finding an interpretive question in a text and reasoning through it:

James Baldwin, “Stranger in the Village”

Octavia Butler, “Bloodchild”

Ursula K. Le Guin, “She Unnames Them”

Toni Morrison, “Recitatif”

ZZ Packer, “Brownies”

David Sedaris, “Repeat After Me”

Alice Walker, “The Revenge of Hannah Kemhuff”

Patricia Williams, “The Emperor’s New Clothes”

EB White, “The Ring of Time” (the whole essay, including the section on Florida and segregation)

Entering a critical conversation about a text:

Build an argument about EB White’s “The Ring of Time” by responding to Craig Seligman’s review “Mr. Normal”

Build an argument about Octavia Butler’s “Bloodchild” by responding to the Butler’s comments in the Afterword about love and slavery

Build an argument about Toni Morrison’s “Recitatif” by responding to two of the following: Morrison’s prologue to Playing in the Dark; Elizabeth Abel’s “Black Writing, White Reading: Race and the Politics of Feminist Interpretation”; David Goldstein-Shirley’s “Race and Response: Toni Morison’s ‘Recitatif’”; and Danielle S. Allen’s prologue, chapter 1, and chapter 9 of Talking to Strangers: Anxieties of Citizenship Since Brown v. Board of Education.

Anne-Elizabeth Brodsky, PhD, has been teaching at Johns Hopkins since 2007 and co-chairs, with Professor Fleming, JHU’s Committee on the Status of Women.

Images source: Pixabay.com

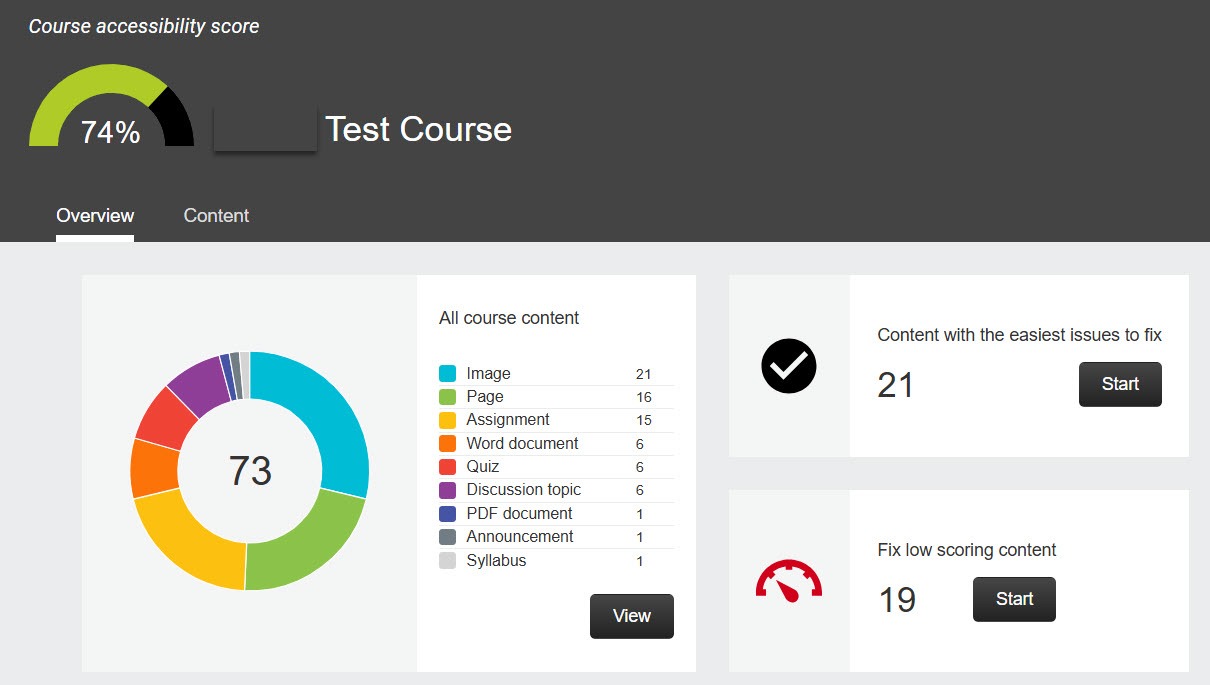

communication, building accessibility into materials from the beginning can prevent barriers before they arise. University-wide guidelines were published in 2021 to ensure that all new content aligns with Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.1 AA. Faculty are expected to make a good-faith, proactive effort to ensure their materials meet these standards and support equitable access for all learners.

communication, building accessibility into materials from the beginning can prevent barriers before they arise. University-wide guidelines were published in 2021 to ensure that all new content aligns with Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.1 AA. Faculty are expected to make a good-faith, proactive effort to ensure their materials meet these standards and support equitable access for all learners.