As the semester gets underway, this is a gentle reminder that faculty are responsible for creating course materials that are accessible to all students. While the start of the term is often packed with course preparation, Canvas/LMS setup, and student communication, building accessibility into materials from the beginning can prevent barriers before they arise. University-wide guidelines were published in 2021 to ensure that all new content aligns with Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.1 AA. Faculty are expected to make a good-faith, proactive effort to ensure their materials meet these standards and support equitable access for all learners.

communication, building accessibility into materials from the beginning can prevent barriers before they arise. University-wide guidelines were published in 2021 to ensure that all new content aligns with Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.1 AA. Faculty are expected to make a good-faith, proactive effort to ensure their materials meet these standards and support equitable access for all learners.

A few best practices to help you get started:

- Use built-in formatting tools for styles, headings (Heading 1, Heading 2, etc.), and lists (bullets, numbers, etc.) to provide structure and easier navigation.

- Ensure PDFs are searchable and selectable (not scanned images).

- Provide meaningful text for all hyperlinks, describing the link’s destination or purpose.

- Use tables for displaying data, not for page layout; be sure to include header rows and defined borders in tables.

For multimedia:

- Use high contrast visuals: dark text on a light background or light text on a dark background; avoid using color as the only way to distinguish highlighted areas of your document/slide.

- Provide Alt Text (short written descriptions) for all non-decorative images, graphs, charts, or other non-textual elements.

- Include captions and transcripts with all videos, including short clips and instructor-created recordings.

Other considerations:

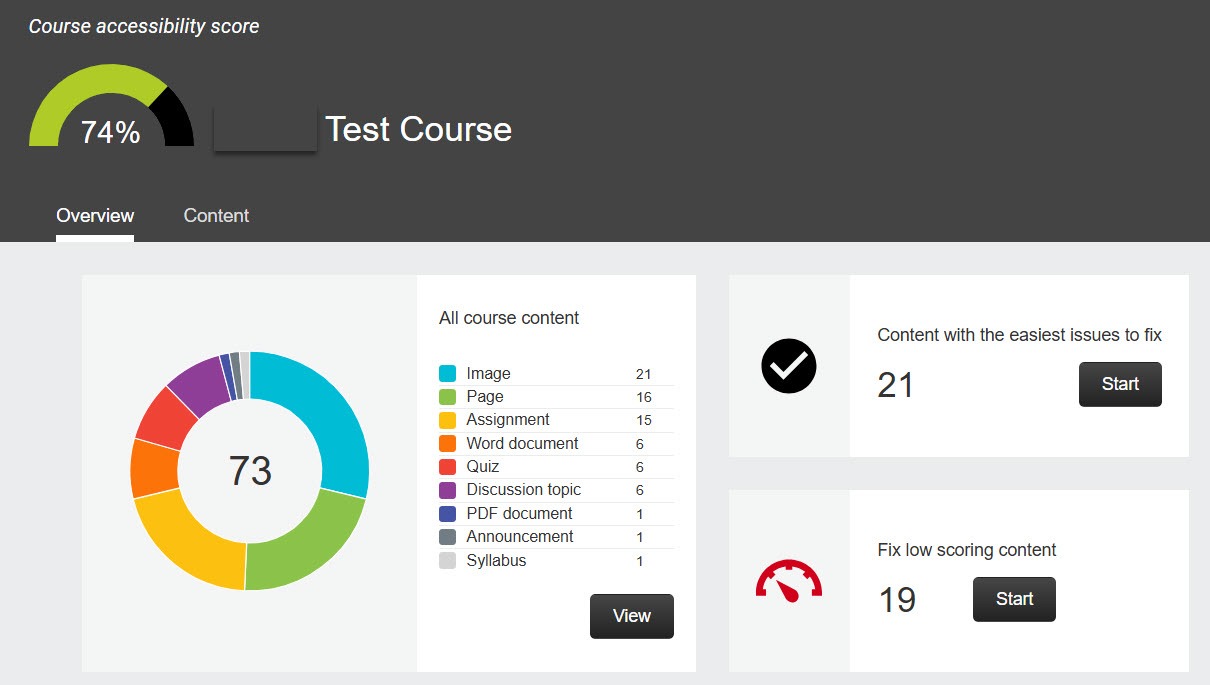

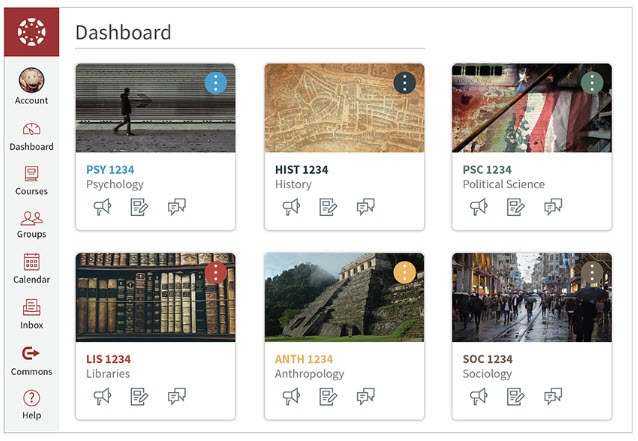

- If you use Canvas, take advantage of the built-in accessibility checker as well as Ally, a third-party tool that flags accessibility issues course-wide, including those found in uploaded external content (such as PDFs).

- In addition to accessibility, applying Universal Design for Learning (UDL) principles can further support diverse learners by offering flexible ways to engage with course content and demonstrate learning:

- Provide materials in more than one format when possible, such as text, images, or video.

- Offer a choice in how students demonstrate their learning: essay, group presentation, written vs. oral exam, etc.

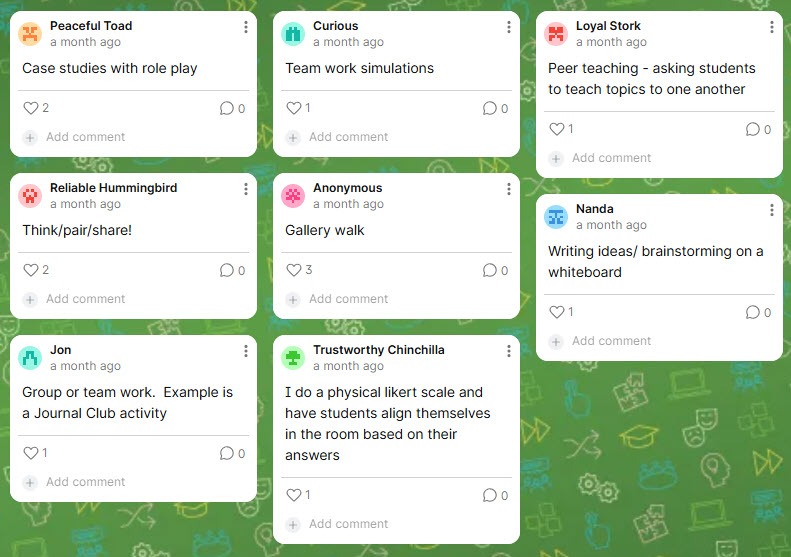

- Provide multiple opportunities for students to engage with course content; some examples include case studies, class discussion, collaboration with peers, guest speakers, and field trips.

This is not a complete list – faculty are encouraged to explore in more detail the university’s resources on how to create an accessible learning environment:

- Accessibility Guidelines for Course Materials from CTEI

- JHU’s Guide to Digital Accessibility

- Teaching Toolkit from BSPH

- Checklist for Making Accessible MS Office and PDF documents

- Hopkins Universal Design for Learning (HUDL)

Do you have additional questions about accessibility? Contact your division’s teaching and learning center for more assistance.

Amy Brusini, Senior Instructional Designer

Center for Teaching Excellence and Innovation

Image source: magele-picture – stock.adobe.com, Canvas screenshot

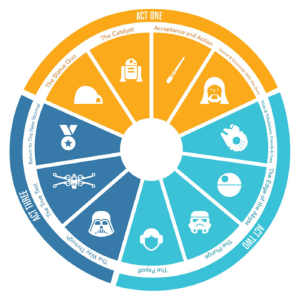

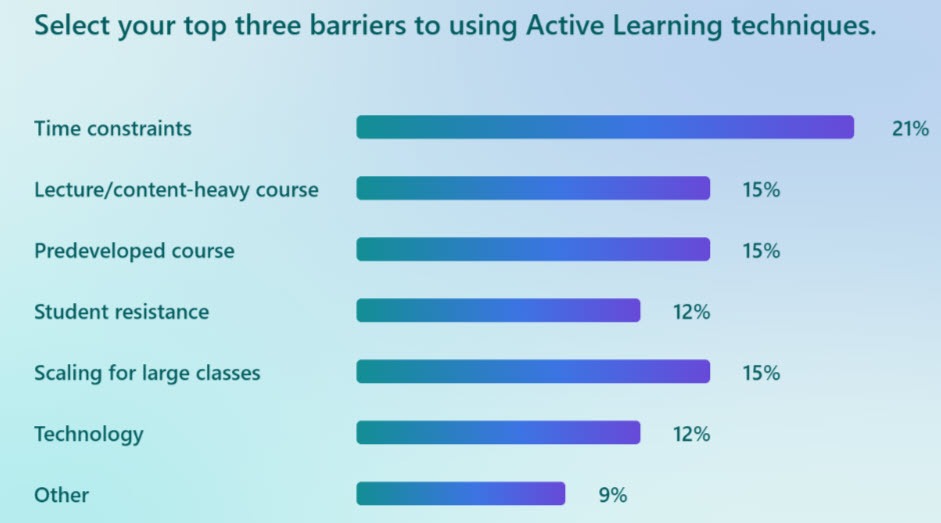

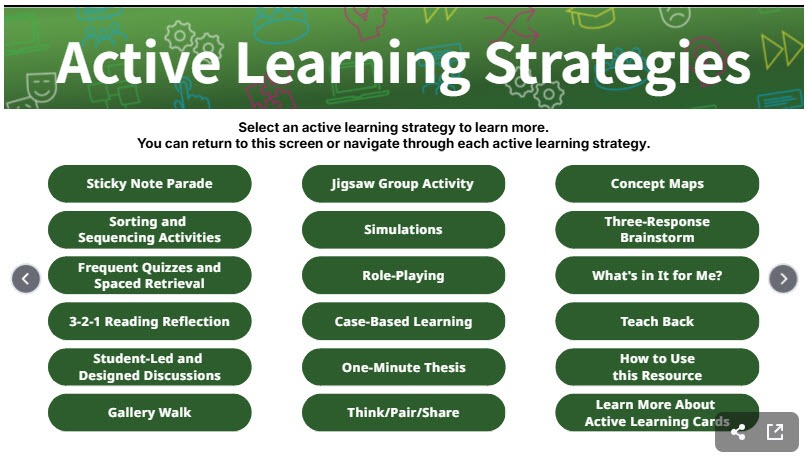

listening to the instructor and taking notes.” Research shows active learning is more effective than lecturing. It helps students learn better through activity and engagement. It falls on a continuum ranging from instructor-focused to student-focused learning. Instructor-focused means high instructor control and low student autonomy. An example of that is an active lecture, where traditional lecturing is interspersed with engaging activities. Student-focused means high student autonomy and low instructor control. Examples include problem-based and project-based learning, which require critical thinking, collaboration, and problem-solving. Shared responsibility is in the middle of the continuum. Examples include structured discussions, guided problem-solving, etc.

listening to the instructor and taking notes.” Research shows active learning is more effective than lecturing. It helps students learn better through activity and engagement. It falls on a continuum ranging from instructor-focused to student-focused learning. Instructor-focused means high instructor control and low student autonomy. An example of that is an active lecture, where traditional lecturing is interspersed with engaging activities. Student-focused means high student autonomy and low instructor control. Examples include problem-based and project-based learning, which require critical thinking, collaboration, and problem-solving. Shared responsibility is in the middle of the continuum. Examples include structured discussions, guided problem-solving, etc. The purpose of learning objectives is to

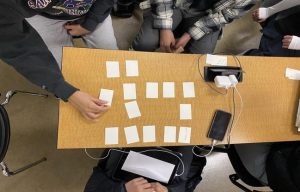

The purpose of learning objectives is to assessment. Assessment is gathering data about the learning process. It is more than just evaluation, where instructors collect data for the purpose of making evaluative and pass/fail judgments. Assessment helps the faculty member facilitate the learning process for students which includes providing feedback to help them improve.

assessment. Assessment is gathering data about the learning process. It is more than just evaluation, where instructors collect data for the purpose of making evaluative and pass/fail judgments. Assessment helps the faculty member facilitate the learning process for students which includes providing feedback to help them improve.