On Tuesday, October 8, 2024, the Center for Teaching Excellence and Innovation (CTEI) hosted the first Lunch and Learn of the Fall 2024 semester. Brian Klaas, Assistant Director for Technology and instructor at the Bloomberg School of Public Health, presented: From Plato to Pixar – Using Storytelling Frameworks to Drive Learner Engagement and Improved Outcomes. Caroline Egan, Teaching Academy Program Manager, moderated the presentation.

(CTEI) hosted the first Lunch and Learn of the Fall 2024 semester. Brian Klaas, Assistant Director for Technology and instructor at the Bloomberg School of Public Health, presented: From Plato to Pixar – Using Storytelling Frameworks to Drive Learner Engagement and Improved Outcomes. Caroline Egan, Teaching Academy Program Manager, moderated the presentation.

Brian Klaas opened the presentation by highlighting the valuable role storytelling plays in the classroom. While sharing facts is essential, building a narrative around those facts provides the context that gives them meaning. When we teach, we enact a narrative; we are telling a story. Stories help students connect abstract or complex ideas to real-world applications, making the content more relatable and engaging. Students are more likely to recall and retain information that resonates with them on some level. Storytelling also encourages students to think critically as they analyze characters, events, and outcomes, which can deepen their understanding of the material.

Klaas went on to describe the four cornerstones of narratives and encouraged audience members to think about how they might apply them to their teaching:

- Conflict: What problem are we trying to solve? What are we trying to overcome? What stories as a presenter can I frame through conflict? Conflict gives us drama and tension.

- Character: How can you draw people into your lectures or stories? We need facts and data, but we also need to engage with the emotional part of the brain. There are many opportunities to include characters/people into your data – including yourself!

- Segmenting: Organizing and chunking information, such as chapters in books, acts in plays, etc., gives our presentation a logical flow. We present one idea at a time, declare why it’s important, before moving on to the next one. Segmenting gives us a sense of moving forward.

- Reflection: What does this mean to me? Why is this important? As educators we can incorporate reflection into our teaching in various ways, including think-pair-share, self-assessment, journaling, etc.

Klaas acknowledged that it can be difficult to make the shift from sharing facts to telling stories. He introduced the audience to two storytelling frameworks that can help with this process: the Hero’s Journey and the Pixar Framework.

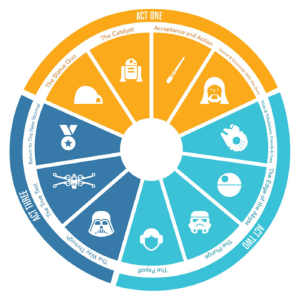

The Hero’s Journey is a popular template that follows the adventures of a hero who faces some sort of conflict, overcomes various obstacles along the way, and eventually emerges victorious. In the process, the hero is transformed in some way, embracing newfound knowledge and lessons learned. Examples of stories that follow this template include: The Lord of the Rings, Harry Potter, and Star Wars. Originally 12 steps, The Hero’s Journey template can be divided into 3 main acts:

The Hero’s Journey is a popular template that follows the adventures of a hero who faces some sort of conflict, overcomes various obstacles along the way, and eventually emerges victorious. In the process, the hero is transformed in some way, embracing newfound knowledge and lessons learned. Examples of stories that follow this template include: The Lord of the Rings, Harry Potter, and Star Wars. Originally 12 steps, The Hero’s Journey template can be divided into 3 main acts:

- Departure/Separation: Where do things stand? This act presents the background, the current cultural context, followed by an event that pushes the hero to begin the journey.

- Initiation: What went wrong? What is the issue? Why can’t we move forward? This act explores the series of challenges faced by the hero that help to create tension and conflict.

- Return: What lessons did we learn? Why does this matter? This act shows what was learned and how the world is changed, why it is meaningful.

Klaas gave an example of a Hero’s Journey story:

He told the audience about one of his former students who traveled to Nigeria to study that country’s waste disposal and sewage system. While there, she noticed a woman repeatedly leaving her hut to go out into the grass. When the student asked why, she was told that the woman recently had a baby, was having some problems, and wasn’t able to engage with the community. The student learned that the woman experienced an obstetric fistula, a serious complication of childbirth that causes women to suffer incontinence, shame, and social segregation. The student went to community leaders and tried to explain to them that this is common, that the woman just needed proper care. The leaders rejected her plea. For the student, this was a lesson in cultural humility. She learned that local hospitals are not equipped to deal with this issue. This encounter led to her to shift her studies to help women deal with this problem. She ended up working on a project to help women in this region.

Klaas noted that the hero does not have to be a person – it could be a cell, for example – and that this framework could be a powerful way to present research to the world.

The Pixar framework, which forms the foundation of animated Pixar films, such as Finding Nemo and Toy Story, uses the following format:

- Once upon a time… (context of the world)

- And every day… (everyday life in that world)

- Until one day… (incident that launches the story)

- And because of this… (the character’s journey)

- And because of that… (new journey the character takes)

- Until finally… (resolution of the story)

This framework can be applied to a number of different areas, such as literature, health sciences, and history. It can be used to tell a story about why things fail or why things change – it doesn’t always have to be a success. Klaas gave the example of how this format could be applied to narrate a problem such as antibiotic resistance:

- Once upon a time… You get an antibiotic every time you go to the

doctor - And every day… Antibiotic-resistant bacteria are on the rise,

and here’s the data to prove it! - Until one day… Strategy for reducing antibiotic

overprescription and sparking new research - And because of this…Reduction in antibiotic-resistant microbes;

increase in funding for new antibiotic research - And because of that… Better health outcomes for people; better

incentives for private research - Until finally… Generations of new antibiotics without living

in fear of paper cuts killing us

Audience members were asked to share their ideas of how they might use this framework in their courses: One guest suggested using the framework to share research findings about high cholesterol with students in a concise manner. Another guest suggested using it to describe the history of drunk driving and the evolution of the breathalyzer test, leading to the development of a handheld alcohol detection device. And another guest suggested using it to talk about climate change in order to facilitate discussion.

share their ideas of how they might use this framework in their courses: One guest suggested using the framework to share research findings about high cholesterol with students in a concise manner. Another guest suggested using it to describe the history of drunk driving and the evolution of the breathalyzer test, leading to the development of a handheld alcohol detection device. And another guest suggested using it to talk about climate change in order to facilitate discussion.

The presentation wrapped up with a brief Q and A session:

Q: How vital is it to center our teaching around one protagonist as opposed to many? BK: Use storytelling where you can. It’s hard to use all the time, but having context makes it relevant. Always look for meaning, something that will be remembered down the line.

Guest: It helps when trying to make data meaningful. Seeing the story of one person works well. Sometimes too many people [as protagonists] is overwhelming, it becomes abstract. But sometimes showing the numbers affected [in terms of data] can be very powerful.

Q: Students have to write personal narratives for their medical school applications; they try to present themselves as the perfect candidate. Do you recommend using storytelling here?

BK: Yes, you can use storytelling in an application. Storytelling comes from written form, so yes, it will work in writing. My son is in the process of writing his college essays – he’s using the Pixar model right now. It made it easier on him to tell the story once he had a backbone.

Q: Could storytelling be used to help students solve math-based problems? Do you see this?

BK: I haven’t used it this way, but a colleague used it to share complicated math and statistics results from his research. I can see it working, through logical proofs. You don’t have to use the whole Pixar framework – you can use 4 of the 6 steps, for example, to make it work for you.

Amy Brusini, Senior Instructional Designer

Center for Teaching Excellence and Innovation

Image source: Lunch and Learn logo, Writer’s Digest, Disney/Pixar

On Wednesday, November 1st, the Center for Teaching Excellence and Innovation (CTEI) hosted a

On Wednesday, November 1st, the Center for Teaching Excellence and Innovation (CTEI) hosted a