[Guest post by Beth Hals, Senior Instructional Technologist in the Center for Teaching Excellence and Innovation (CTEI), Johns Hopkins University]

Thoughtful course design plays a critical role in shaping the student learning experience, regardless of whether a class is taught online or in person. Fully online asynchronous courses typically have an intense, front-loaded design process to ensure that they are accessible, easy to navigate, and designed in a comprehensive manner.  These courses often come with instructional design support as well. For instructors delivering synchronous courses, by the time they have constructed their syllabus, designed their assessments, created lectures, and determined what strategies will be used in class to encourage student engagement, designing and building their Canvas course sites may understandably be at the bottom of the list.

These courses often come with instructional design support as well. For instructors delivering synchronous courses, by the time they have constructed their syllabus, designed their assessments, created lectures, and determined what strategies will be used in class to encourage student engagement, designing and building their Canvas course sites may understandably be at the bottom of the list.

But course design matters. It impacts the students’ perception of the course and their learning experience. During JHU’s Spring 2024 Canvas Implementation Survey, when asked about their user experience in an open-ended question, student responses included: “every class is some new labyrinth,” “some classes are terrible because the courses are not set up well in the system,” and “the difference between a chaotic and stressful canvas course and an easy-to-use one is organization.”

As a senior instructional technologist, I work directly with faculty who are trying to do just this – communicate with their students using the online platform, disseminate content, organize their resources in logical and meaningful ways, and leverage the learning management system (LMS) in a way that accomplishes exactly what they want for their assignments and gradebook calculations. The good news is that while creating a Canvas course may not be an instructor’s top priority, there are several tweaks one can make to significantly improve students’ experiences and overall course design.

Communication around course expectations

You may have the most beautiful course outline ever created within the confines of your syllabus, but is that same outline reflected within your course resources and assignments? The easier it is for students to locate the outline, which undoubtedly contains critical information such as due dates, the more likely they are to access it and meet your expectations!

- Help students plan: make sure all assignments, quizzes, discussions, etc. have due dates.

- When you include due dates, they appear in the student’s Canvas Calendar synthesized with due dates from all of their other courses. Due dates are also viewable in the student’s to-do list and in their DXP calendar (the DXP calendar is part of the digital experience platform in which students can access a synthesized view of their schedule, major university events or holidays, Canvas and Course Plus assignments, and more).

-

-

- If students have a multi-part assignment, a discussion that involves posting and responding to their peers in some way, or participate in a

peer review, provide each of these checkpoint dates explicitly, as all of these types of assignments require multiple due dates.

peer review, provide each of these checkpoint dates explicitly, as all of these types of assignments require multiple due dates. - Set a to-do date on critical Canvas pages. If you have a page in which you explain what reading needs to be completed before coming to class, set a to-do date for that page and outline the pre-class expectations.

- If students have a multi-part assignment, a discussion that involves posting and responding to their peers in some way, or participate in a

-

- Eliminate hunting: If you use assignments, quizzes, or discussions in your course, make sure they are available to students on the Course Navigation Menu and include detailed instructions.

-

- Students should not have to hunt for assignment instructions or discussion prompts in the syllabus. Include this information in the instructions area of your assignment or discussion board.

- Students need to be able to quickly refer back to your course to clarify instructions, check and respond to discussion threads, and access an assignment to easily submit their work. The Course Navigation Menu provides easy access to key areas of the course.

Give your course personality

A warm, positive online presence is vitally important to cultivating a sense of community for your students. There are several ways you can use the LMS to help your course feel more approachable and inviting:

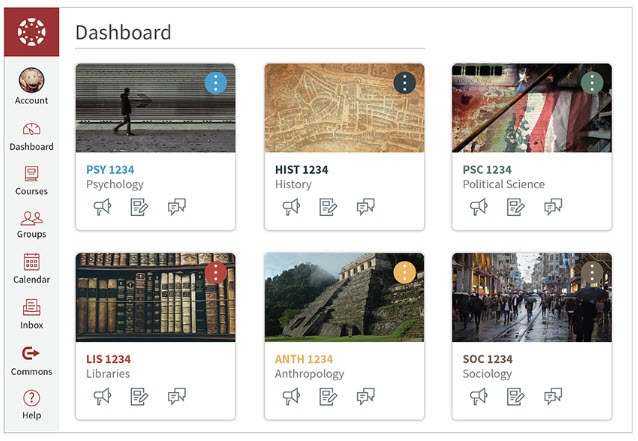

- Course Card Image: Upload an image to represent your Canvas course. This creates a visual association that will differentiate your course from the others.

- Canvas Profile Picture: Upload a picture of yourself or something that represents your personality to your Canvas profile. This picture appears when you make an announcement, provide a summary comment in SpeedGrader, or comment on discussion posts and helps your communication feel more personalized.

- Create an Instructor Profile or an About Me Page: Provide students with information about yourself and your professional background – but be sure to also include some personal details, such as hobbies, personal interests, pets, family, favorite vacation, etc. Creating an opportunity for students to discover common interests while also humanizing yourself helps build rapport and makes you more approachable.

Make your course accessible for all

- Use Built-in Accessibility Checkers

Canvas includes a built-in Accessibility Checker that checks content created within the Rich Content Editor. Canvas also integrates with Ally, a third-party tool that flags issues course-wide, including those found in uploaded external content, and provides instructions on how to fix them. These tools quickly identify issues such as missing alternative text, poor color contrast, and inaccessible document formats. Regularly running checks using these tools helps instructors make timely improvements and maintain an inclusive course site.

as missing alternative text, poor color contrast, and inaccessible document formats. Regularly running checks using these tools helps instructors make timely improvements and maintain an inclusive course site.

- Apply Universal Design for Learning (UDL)

Designing with UDL principles in mind ensures your course meets the needs of a wide range of learners. Providing multiple means of engagement, representation, and expression not only supports students with disabilities but also improves learning experiences for all students. For example, if your course contains several text-heavy documents, you might consider also including a relevant set of images and/or videos. Conversely, consider providing a transcript for any videos within your course.

- Provide Clear, Organized Content

Structuring materials with headings, descriptive links, and consistent formatting makes content easier to navigate with screen readers and less overwhelming for all students. Use built-in bullet points or numbered lists to help organize content. A well-organized course site reduces cognitive load and helps students focus on learning rather than searching for resources. If your school does not use formatting software (i.e., CidiLabs, etc.) consider using CTEI’s Canvas Formatting Toolkit to help organize your course site. Pre-formatted tabs, callout boxes, icons and more are available for download from Canvas Commons. If you are external to JHU, send an email to ctei@jhu.edu for assistance with the toolkit.

Ask a friend (or your teaching and learning center!)

Do you think everything in your course is laid out beautifully? Is it easy to understand what the course expectations are and when everything is due? Ask a colleague, TA, friend, family member, or your teaching and learning center to take a look at your course while in Student View. Can they easily find what a student needs to be successful?

Do you have any additional suggestions for tweaking your Canvas course? Please share them in the comments below!

Beth Hals, Senior Instructional Technologist

Center for Teaching Excellence and Innovation

Image sources: Pixabay, Canvas screenshots, University of Oklahoma Online and Academic Technology Services

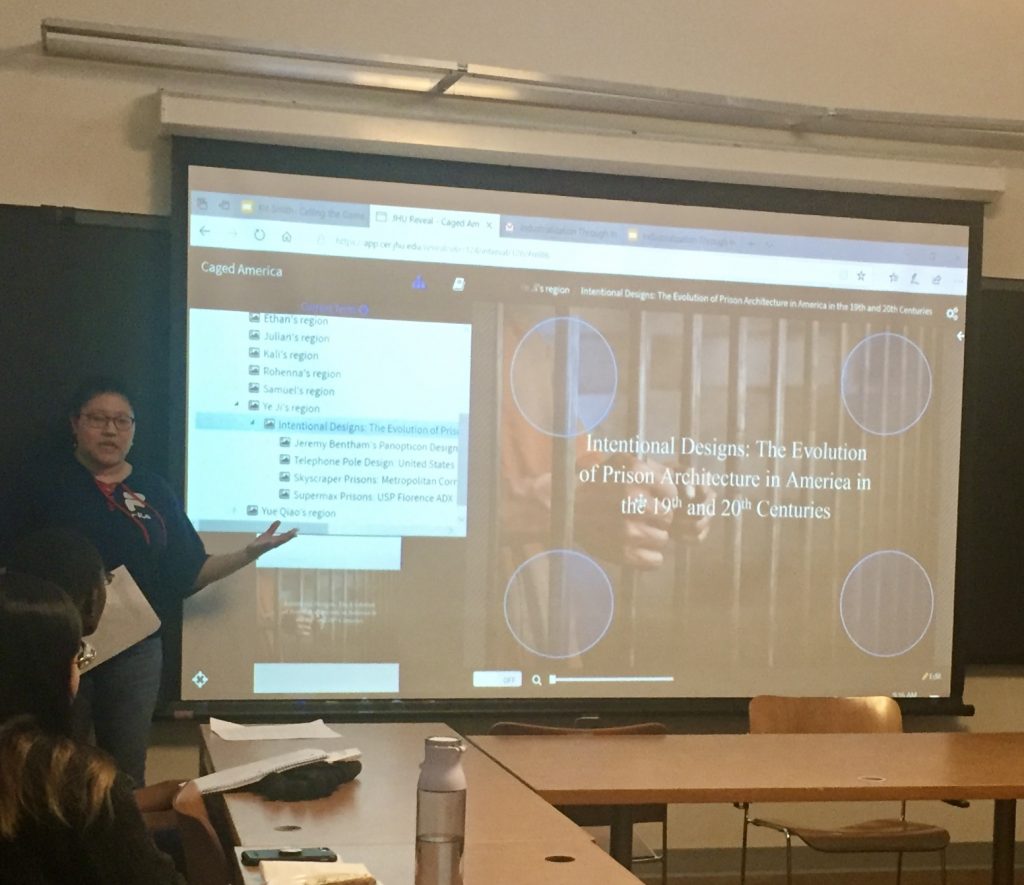

listening to the instructor and taking notes.” Research shows active learning is more effective than lecturing. It helps students learn better through activity and engagement. It falls on a continuum ranging from instructor-focused to student-focused learning. Instructor-focused means high instructor control and low student autonomy. An example of that is an active lecture, where traditional lecturing is interspersed with engaging activities. Student-focused means high student autonomy and low instructor control. Examples include problem-based and project-based learning, which require critical thinking, collaboration, and problem-solving. Shared responsibility is in the middle of the continuum. Examples include structured discussions, guided problem-solving, etc.

listening to the instructor and taking notes.” Research shows active learning is more effective than lecturing. It helps students learn better through activity and engagement. It falls on a continuum ranging from instructor-focused to student-focused learning. Instructor-focused means high instructor control and low student autonomy. An example of that is an active lecture, where traditional lecturing is interspersed with engaging activities. Student-focused means high student autonomy and low instructor control. Examples include problem-based and project-based learning, which require critical thinking, collaboration, and problem-solving. Shared responsibility is in the middle of the continuum. Examples include structured discussions, guided problem-solving, etc. The purpose of learning objectives is to

The purpose of learning objectives is to assessment. Assessment is gathering data about the learning process. It is more than just evaluation, where instructors collect data for the purpose of making evaluative and pass/fail judgments. Assessment helps the faculty member facilitate the learning process for students which includes providing feedback to help them improve.

assessment. Assessment is gathering data about the learning process. It is more than just evaluation, where instructors collect data for the purpose of making evaluative and pass/fail judgments. Assessment helps the faculty member facilitate the learning process for students which includes providing feedback to help them improve.

On Wednesday, November 1st, the Center for Teaching Excellence and Innovation (CTEI) hosted a

On Wednesday, November 1st, the Center for Teaching Excellence and Innovation (CTEI) hosted a