On Wednesday, October 16, the Center for Educational Resources (CER) hosted the first Lunch and Learn for the 2019-2020 academic year. Steve Marra, Associate Teaching Professor, Mechanical Engineering, Susan Weiss, Associate Professor, jointly appointed in Musicology at the Peabody Institute and the Department of Modern Languages in the Krieger School of Arts and Sciences, and Nathan Scott, Associate Teaching Professor, Mechanical Engineering presented on Teaching a Multi-Disciplinary Course.

On Wednesday, October 16, the Center for Educational Resources (CER) hosted the first Lunch and Learn for the 2019-2020 academic year. Steve Marra, Associate Teaching Professor, Mechanical Engineering, Susan Weiss, Associate Professor, jointly appointed in Musicology at the Peabody Institute and the Department of Modern Languages in the Krieger School of Arts and Sciences, and Nathan Scott, Associate Teaching Professor, Mechanical Engineering presented on Teaching a Multi-Disciplinary Course.

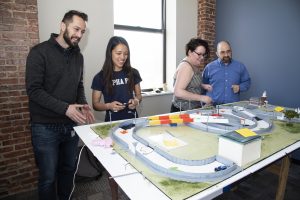

Steve Marra began the presentation by describing an Interdisciplinary Multi-Institutional Design Experience for Freshman Engineering and Art Students that took place in the Spring of 2018. This was a joint project initiated by instructors from JHU and the Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA). There were 44 students from JHU and 34 students from MICA who participated in the project. Marra described the project as having purposely vague specifications in order to allow for as much creativity as possible. Teams were given $100 to build something safe and interactive, with a variety of hard and soft materials over the course of 13 weeks that would “make your world better.” Each school determined its own grading schema; JHU students were graded on design reports and project notebooks, MICA students were graded on preliminary sketches and documentation, and all students were graded on quality of work. The project culminated with a week-long exhibition at MICA at the end of the semester.

This was a joint project initiated by instructors from JHU and the Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA). There were 44 students from JHU and 34 students from MICA who participated in the project. Marra described the project as having purposely vague specifications in order to allow for as much creativity as possible. Teams were given $100 to build something safe and interactive, with a variety of hard and soft materials over the course of 13 weeks that would “make your world better.” Each school determined its own grading schema; JHU students were graded on design reports and project notebooks, MICA students were graded on preliminary sketches and documentation, and all students were graded on quality of work. The project culminated with a week-long exhibition at MICA at the end of the semester.

Marra continued by describing obstacles encountered when implementing this project. One of the most significant challenges was scheduling and transporting students between campuses. While the faculty had considered this might pose a challenge in the initial stages of the project, transportation and scheduling conflicts were more of an issue than expected. Another challenge was the separation/isolation of work within student groups; in general, engineering students embraced the engineering tasks while art students gravitated toward the artistic tasks. They did work with each other but took on a ‘divide and conquer’ approach in most cases, rather than collaborating as much as the faculty had hoped.

Other unexpected challenges included:

- Conflicting advice given to students by instructors. Marra commented that there was not enough collaboration between instructors ahead of time.

- Staggered spring breaks between the two schools, resulting in two weeks of no work getting accomplished.

- Multitude and diversity of projects due to vague assignment specifications. Marra commented that diversity of projects is normally celebrated, but in this case it made it difficult to efficiently assist students with their projects.

Despite the various challenges, student teams met their deadlines and created 18 projects in all for the exhibition. These included: a hugging machine, mega backpack, relaxation station, and a marble run. Marra concluded with suggestions for improvement:

Despite the various challenges, student teams met their deadlines and created 18 projects in all for the exhibition. These included: a hugging machine, mega backpack, relaxation station, and a marble run. Marra concluded with suggestions for improvement:

- Plan early

- Develop a more focused assignment with very clear specifications

- Schedule a kickoff meeting with icebreakers

- Take time to teach teamwork and conflict resolution

- Provide instruction on ideation

- Develop an advising strategy

- Do not underestimate the importance of convenient transportation

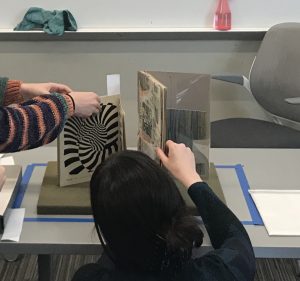

Susan Weiss continued the presentation by describing the course she co-teaches with Nathan Scott, History and Technology of Musical Instruments, which is offered jointly by ASEN and Peabody. Students are tasked with building their own instruments from scratch or repairing broken instruments in various states of disrepair. Materials used have expanded from simple cigar boxes and PCV pipe to much more sophisticated materials as the course has progressed and more funding has become available. Weiss noted that the content and direction of the course depends on the guests that are available to come in and work with the students during the semester, such as luthiers, professional musicians, guest speakers, etc. Students are graded on journal entries, weekly reflections, and presentations.

Weiss went on to describe some of the challenges with this course. One of the biggest challenges is the constant struggle to find a space for students to construct the instruments. In the past, students have used maker spaces at Homewood but most recently have been using a room in the basement of Peabody’s Leakin Hall. Finding the necessary raw materials can also be a challenge especially with budgetary constraints. Weiss also mentioned how students in this course tend to gravitate to their area of expertise, but that they have checks in place to ensure that students are sharing tasks equitably and learning from each other’s strengths.

Despite its challenges, the course continues to grow and evolve. When it first started, students were making cigar box guitars and other small instruments.  Two years ago students built banjos; this past year, they took on the challenge of building cellos which they had the opportunity to play at the Whiting School of Engineering’s Design Day. Weiss noted how highly students rate this course and how much they appreciate the unique opportunity to collaborate and learn from other students.

Two years ago students built banjos; this past year, they took on the challenge of building cellos which they had the opportunity to play at the Whiting School of Engineering’s Design Day. Weiss noted how highly students rate this course and how much they appreciate the unique opportunity to collaborate and learn from other students.

Nathan Scott extended the presentation into a more philosophical discussion of what it means to be a student who embraces multi-disciplinary studies. He likened a student who is not merely after a degree to a child who grows up in a bilingual or multilingual home. That child, he stated, not only learns multiple languages naturally, but also has a brain now trained to learn skills more readily or easily than a child not exposed to multiple languages. He referred to this child as a ‘super learner.’

Scott noted that most research at JHU is multi-disciplinary and that there are fantastic opportunities for undergraduates to take part in this research and experience ‘super learning.’ He believes that our university, as a whole, could better design curriculum to ensure multi-disciplinary education for all students. He suggested adding a graduation requirement for all WSE majors to complete a substantial, two-semester capstone project. No classes would be held on Fridays, which would become ‘project days,’ so students from all majors could work together in teams to complete their projects. In addition, students would have a collaborative space that would be their ‘home’ throughout their undergraduate years to develop community.

Below are some questions from audience members with answers from the presenters.

Q: (for Marra) The MICA/JHU course was worth one credit; wasn’t that a great deal of work for faculty and students?

Marra responded that while the course was only one credit, it was worth it because of the learning that occurred. However, if he did this project again, he would make some significant changes, such as limiting it to only Hopkins students to minimize the issues with logistics and schedules. Marra did note that the credit hours rarely are a true reflection of the work necessary for the course by students or faculty.

Q: (for all) What is the payoff of the interdisciplinary course?

Scott reported that employers are hungry to hear about these experiences and meet students who have completed multi-disciplinary projects, not just taken x course or y course. His ideal would be to have a campus design center where artists and experts in residence bring their skills to JHU and have student apprentices.

Marra remarked that interdisciplinary skills are different than team skills and that employers are recognizing the value of interdisciplinary skills. Students are often uncomfortable working in these types of environments and grow from the experience.

Weiss noted that students don’t necessarily have skills in one area or another, but as they collaborate, they discover each other’s abilities, and it is a revelation for them.

Q: (for Marra) How would you manage the issue of students gravitating toward their area of expertise if you ran this project again?

Marra responded that he would make it some sort of requirement that students demonstrate skills in their non-dominant major or skill set.

Read more about Steve Marra’s project in a recent HUB article. Read more about Susan Weiss and Nathan Scott’s course in this Peabody Post article.

Amy Brusini, Senior Instructional Designer

Center for Educational Resources

Photo credits: Steve Marra and Susan Weiss

After 31 years at Johns Hopkins University, 11 in the Center for Educational Resources, six years and 198 posts on The Innovative Instructor, I am retiring. The good news is that my colleague, Amy Brusini, will be taking on the mantle, not only as the new editor of this blog, but as the Senior Instructional Designer in the CER.

After 31 years at Johns Hopkins University, 11 in the Center for Educational Resources, six years and 198 posts on The Innovative Instructor, I am retiring. The good news is that my colleague, Amy Brusini, will be taking on the mantle, not only as the new editor of this blog, but as the Senior Instructional Designer in the CER.