On Tuesday, April 23rd, the Center for Teaching Excellence and Innovation (CTEI) hosted a Lunch and Learn on Generative AI Uses in the Classroom. Faculty panelists included Louis Hyman, Dorothy Ross Professor of Political Economy in History and Professor at the SNF Agora Institute, Jeffrey Gray, Professor of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering in the Whiting School, and Brian Klaas, Assistant Director for Technology and instructor at the Bloomberg School of Public Health. Caroline Egan, Teaching Academy Program Manager, moderated the discussion.

Technology and instructor at the Bloomberg School of Public Health. Caroline Egan, Teaching Academy Program Manager, moderated the discussion.

Louis Hyman began the presentation by reminding the audience what large language models (LLMs) like ChatGPT can and cannot do. For example, ChatGPT does not “know” anything and is incapable of reasoning. It generates text that it predicts will best answer the prompt it was given, based on how it was trained. In addition to his course work, Hyman mentioned several tasks he uses ChatGPT to assist with, including text summarization, writing complicated Excel formulas, writing and editing drafts, making PowerPoint tables, and turning image files in the right direction.

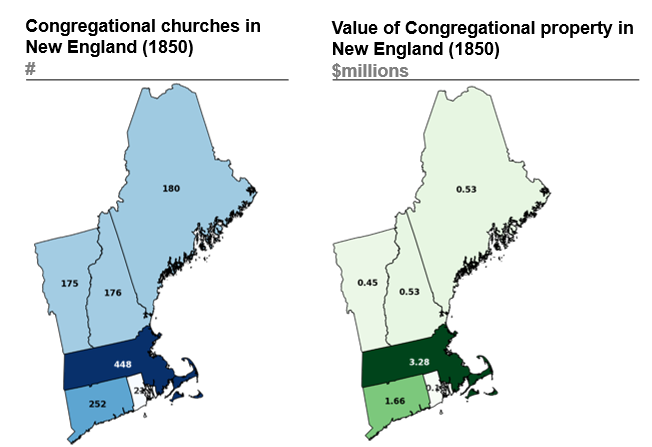

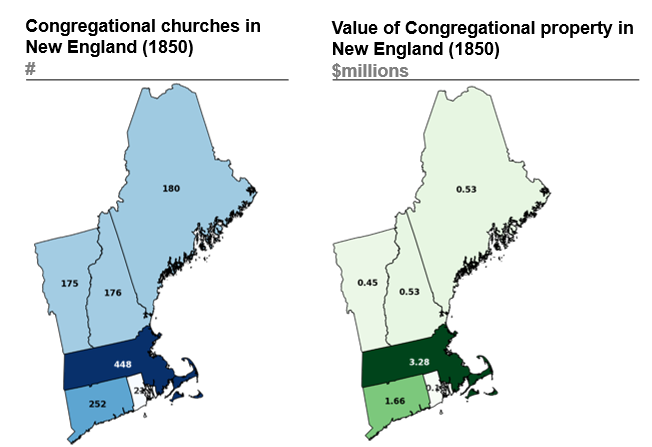

In Hyman’s course, AI and Data Methods in History, students are introduced to a variety of tools (e.g., Google Sheets, ChatGPT, Python) that help them analyze and think critically about historical data. Hyman described how students used primers from LinkedIn Learning as well as Generative AI prompts to increase their technical skills which enabled them to take a deeper dive into data analysis. For example, while it would have been too complicated for most students to write code on their own, they learned how to prompt ChatGPT to write code for them. By the end of the semester, students used application programming interface (API) calls to send data to Google, used OpenAI to clean up historical documents and images presented using optical character recognition (OCR), and used ChatGPT and Python to plot and map historical data.

Hyman noted that one of the most challenging parts of the course was convincing students that it was OK to use ChatGPT, that they were not cheating. Another challenge was that many students lacked basic computer literacy skills, therefore, getting everyone up to speed took some time. There was also not one shared computer structure/platform. The successes of the course include students’ ability to use libraries and APIs to make arguments in their data analysis, apply statistical analysis of the data, and ask historical questions about the results they were seeing in the data.

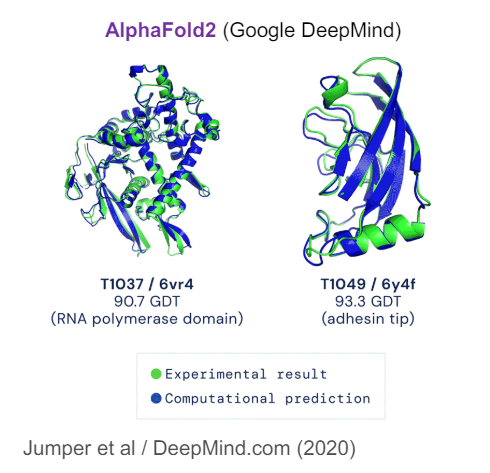

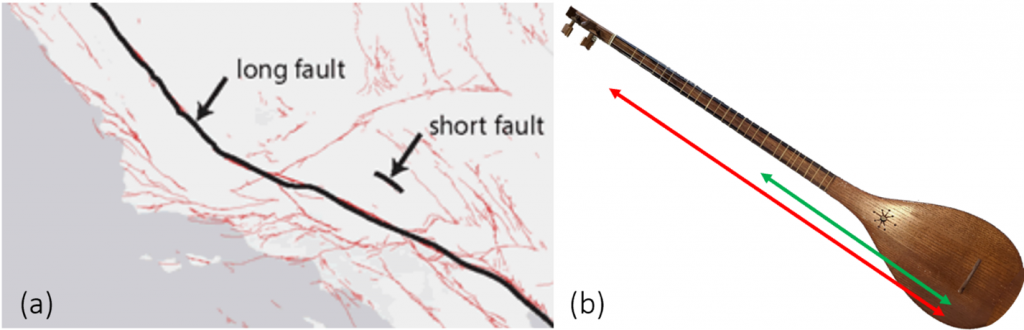

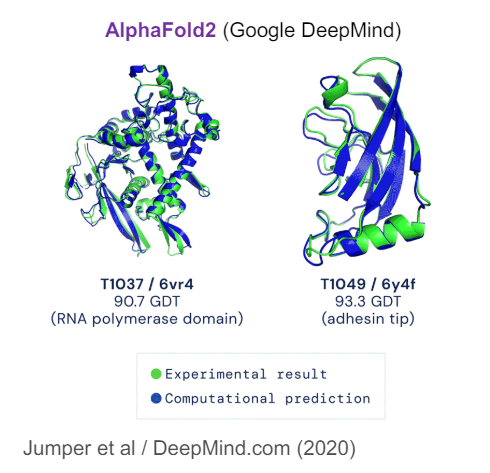

Jeff Gray continued by describing his Computational Protein Structure Prediction and Design course that he has taught for over 18 years. In this course, students use molecular visualization and prediction tools like PyRosetta, an interactive Python-based interface that allows them to design custom molecular modeling algorithms. Recently, Gray has introduced open-sourced AI tools into the curriculum (AlphaFold and RoseTTAFold), which predict 3D models of protein structures.

One of the challenges Gray mentioned was the diversity of student academic backgrounds. There were students from engineering, biology, bioinformatics, computer science, and applied math, among others. To accommodate this challenge, Gray used specifications grading, a grading method in which students are graded pass/fail on individual assessments that align directly with learning goals. In Gray’s class, students were presented with a bundle of problem sets categorized at various difficulty levels. Students selected which ones they wanted to complete and had the option of resubmitting them a second time for full credit. Gray is undecided about using this method going forward, noting that half of the students ended up dropping the course when they tried to complete all of the problems instead of just a few, and found the workload too heavy. Another challenge was how to balance the fundamental depth of the subject matter versus application. To address this, Gray structured the twice weekly class with a lecture on one day and a hands-on workshop the other day, which seemed to work well.

Brian Klaas teaches a one credit pass/fail course called Using Generative AI to Improve Public Health. The goal of this course is to allow students to explore AI tools, gain a basic understanding of how they work, and then apply them to their academic work and research. In addition to using the tools, students discussed the possible harms in Generative AI, such as confabulations, biases, etc., the impact of these tools in Public Health research, and future concerns such as the impact on the environment and copyright law. Klaas shared his syllabus statement regarding the usage of AI tools in class, something he strongly recommends all faculty share with their students.

Hands-on assignments included various ways of using Generative AI. In one assignment, students were asked to write a summary of a journal article and then have GenAI write a summary of the same article geared towards different audiences (academics vs. high school students). Students were then asked to analyze the differences between the summaries. For another assignment, students were asked to pick from a set of topics and use Generative AI to teach them about the selected topic, noting any confabulations or biases present. They then asked GenAI to create a five-question quiz on the topic and take the quiz. A final assignment was to create an Instagram post on the same topic including a single image and a few sentences explaining the topic to a lay audience. All assignments included a reflection piece which often required peer review.

For another assignment, students were asked to pick from a set of topics and use Generative AI to teach them about the selected topic, noting any confabulations or biases present. They then asked GenAI to create a five-question quiz on the topic and take the quiz. A final assignment was to create an Instagram post on the same topic including a single image and a few sentences explaining the topic to a lay audience. All assignments included a reflection piece which often required peer review.

Lessons learned: Students loved the interdisciplinary approach to the course, confabulations reinforce core data research skills, and learning from each other is key.

The discussion continued with questions from the audience:

Q: What would you recommend to an instructor who is considering implementing GenAI in the classroom? How do they start thinking about GenAI?

JG: Jupyter notebooks are pretty easy to use. I think students should just give it a try.

LH: I recommend showing students what ”bad” examples look like. The truth is, we can still write better than computers. Use AI to draft papers and then use it as an editing tool – it’s very good as an editing tool. Students can learn a lot from that.

BK : I recommend having students experiment and see where the strengths lie, get an overall awareness of it. Reflect on that process, see what went well, not so well. Feed in an assignment and see what happens. Use a rubric to evaluate the assignment. Put a transcript in and ask it to create a quiz on that information. It can save you some time.

Q for Brian Klaas: What version of GPT were you using?

BK: Any of them – I didn’t prescribe specific tools or versions. We have students all over the world, so they used whatever they had. ChatGPT, Claude, MidJourney, etc. I let the students decide and allowed them to compare differences.

Q for Jeff Gray: Regrading the number of students who dropped, is the aim of the course to have as many students as possible, or a group who is wholly into it?

JG: I don’t know, I’m struggling with this. I want to invite all students but also need to be able to dig into the math and material. It feels like we just scratched the surface. Maybe offering an intersession course to learn the tools before they take this class would be helpful. There is no standard curriculum yet for AI. Where to begin…we’re all over the map as far as what should be included in the curriculum.

LH: I guess it depends on what your goals are. Students are good at “plug and chug,” but bad at asking questions like, “what does this mean?”

BK: We didn’t get to cover everything, either – there is not enough time in a one credit class. There are just so many things to cover.

Q: What advice do you have for faculty who are not computer scientists? Where should we start learning? What should we teach students?

LH: You can ask it to teach you Python, or how to do an API call. It’s amazing at this. I don’t know coding as well as others, but it helps. Just start asking it [GenAI]. Trust it for teaching something like getting Pytorch running on your PC. Encourage students to be curious and just start prompting it.

BK: If you’re not interested in Jupyter notebooks, or some of the more complicated functions, you can use these tools without dealing in data science. It can do other things. It’s about figuring out how to use it to save time, for ideation, for brainstorming.

JG: I have to push back – what if I want to know about what’s going on in Palestine and Israel? I don’t know what I don’t know. How do I know what it’s telling me is correct?

LH: I don’t use it for history – but where is the line of what it’s good and not good at?

BK: I would use it for task lists, areas to explore further, but remember that it has no concept of truth. If you are someone who knows something about the topic, it does get you over the hurdles.

JG: You have to be an expert in the area to rely on it.

LH: Students at the end of my course made so much progress in coding. It depends on what you ask it to do – protein folding is very different than history that already happened.

Q: How can we address concerns with fairness and bias with these tools in teaching?

BK: Give students foundational knowledge about how the tools work. Understand that these are prediction machines that make stuff up. There have been studies done that show how biased they are, with simple prompts. Tell students to experiment – they will learn from this. I suggest working this in as a discussion or some practice for themselves.

Q: Students have learned to ask questions better – would you rather be living now with these tools, or without them?

JG: Students are brainstorming better. They are using more data and more statistics.

BK: AI requires exploration and play to get good responses. It really takes time to learn how to prompt well. You have to keep trying. Culturally, our students are optimized for finding the “right answer;” AI programs us to think that there are multiple answers. There is no one right answer for how to get there.

LH: Using AI is just a different process to get there. It’s different than what we had to do in college. It was hard to use computers because many of us had to play with them to get things to work. Now it all works beautifully with smart phones. Students today aren’t comfortable experimenting. How do we move from memorization to asking questions? It’s very important to me that students have this experience. It’s uncomfortable to be free and questioning, and then go back to the data. How do we reconcile this?

JG: What age is appropriate to introduce AI to kids?

LH: Students don’t read and write as much as they used to. I’m not sure about the balance.

Guest: I work with middle and high school teachers. Middle school is a great time to introduce AI. Middle school kids are already good at taking information in and figuring out what it means. Teachers need time to learn the tools before introducing it to students, including how the tools can be biased, etc.

Q: How can we encourage creative uses of AI?

BK: Ethan Mollick is a good person to follow regarding creative uses of AI in education and what frameworks are out there. To encourage creativity, the more we expose AI to students, the better. They need to play and experiment. We need to teach them to push through and figure things out.

LH: AI enables all of us to do things now that weren’t possible. We need to remember it’s an augment to what we do, not a substitute for our work.

Resources:

Hyman slides

Gray slides

Klaas slides

Amy Brusini, Senior Instructional Designer

Center for Teaching Excellence and Innovation

Image source: Lunch and Learn logo, Hyman, Gray, and Klaas presentation slides, Unsplash

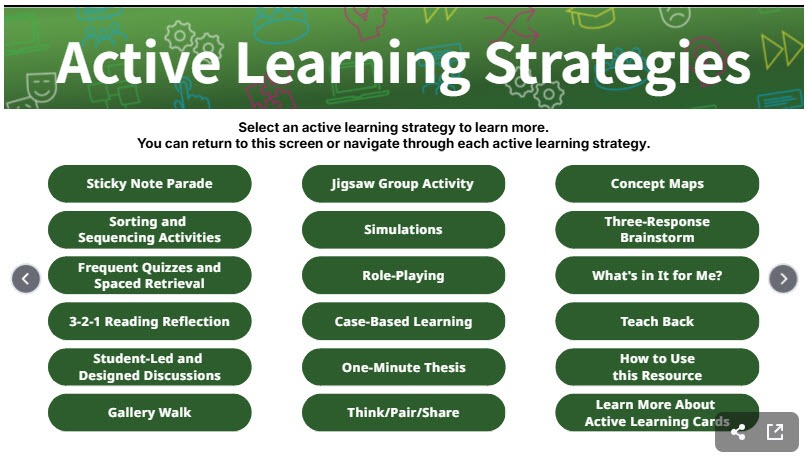

Program Manager and Lecturer in the University Writing Program, developed the content and authored the cards. Beth Hals, Senior Instructional Technologist in the CTEI, created the online resource as well as the extension elements for each of the strategies. Both Caroline Egan and Beth Hals facilitated the session, which was hybrid, with both in-person and online participants.

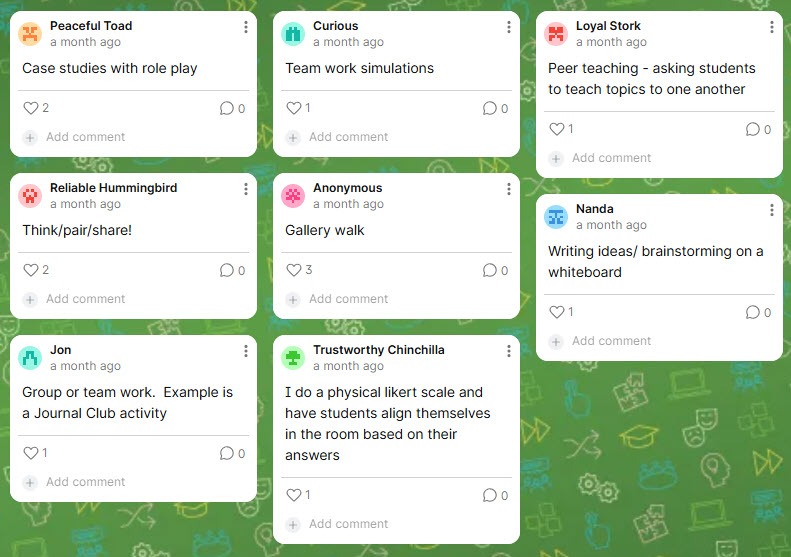

Program Manager and Lecturer in the University Writing Program, developed the content and authored the cards. Beth Hals, Senior Instructional Technologist in the CTEI, created the online resource as well as the extension elements for each of the strategies. Both Caroline Egan and Beth Hals facilitated the session, which was hybrid, with both in-person and online participants. This led to a lively share-out among audience members who were interested in hearing about their peers’ experiences with the strategies they shared, as well as interest in Padlet. Audience responses included: a gallery walk, think-pair-share, group work, brainstorming, case studies, peer instruction, stations, and a jigsaw activity.

This led to a lively share-out among audience members who were interested in hearing about their peers’ experiences with the strategies they shared, as well as interest in Padlet. Audience responses included: a gallery walk, think-pair-share, group work, brainstorming, case studies, peer instruction, stations, and a jigsaw activity.

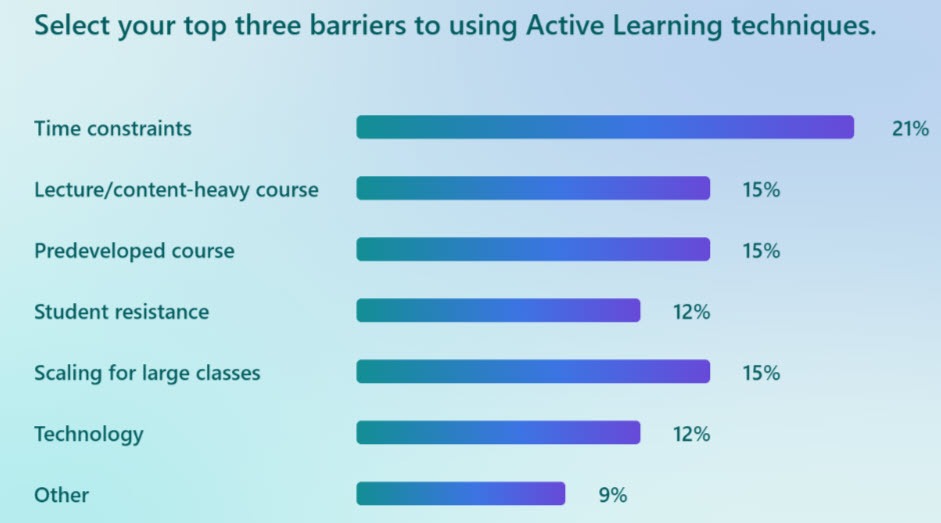

listening to the instructor and taking notes.” Research shows active learning is more effective than lecturing. It helps students learn better through activity and engagement. It falls on a continuum ranging from instructor-focused to student-focused learning. Instructor-focused means high instructor control and low student autonomy. An example of that is an active lecture, where traditional lecturing is interspersed with engaging activities. Student-focused means high student autonomy and low instructor control. Examples include problem-based and project-based learning, which require critical thinking, collaboration, and problem-solving. Shared responsibility is in the middle of the continuum. Examples include structured discussions, guided problem-solving, etc.

listening to the instructor and taking notes.” Research shows active learning is more effective than lecturing. It helps students learn better through activity and engagement. It falls on a continuum ranging from instructor-focused to student-focused learning. Instructor-focused means high instructor control and low student autonomy. An example of that is an active lecture, where traditional lecturing is interspersed with engaging activities. Student-focused means high student autonomy and low instructor control. Examples include problem-based and project-based learning, which require critical thinking, collaboration, and problem-solving. Shared responsibility is in the middle of the continuum. Examples include structured discussions, guided problem-solving, etc. The purpose of learning objectives is to

The purpose of learning objectives is to assessment. Assessment is gathering data about the learning process. It is more than just evaluation, where instructors collect data for the purpose of making evaluative and pass/fail judgments. Assessment helps the faculty member facilitate the learning process for students which includes providing feedback to help them improve.

assessment. Assessment is gathering data about the learning process. It is more than just evaluation, where instructors collect data for the purpose of making evaluative and pass/fail judgments. Assessment helps the faculty member facilitate the learning process for students which includes providing feedback to help them improve.